General Adaptation Syndrome

-

Selected excerpts from The Physiology and Pathology of Exposure to Stress, A Treatise Based on the Concept of the General Adaptation Syndrome and the Diseases of Adaptation by Hans Selye (1950)

Principal Facts and Theories

First the main facts:

(1) Various stresses, which affect large portions of the body (cold, fatigue, infections, intoxications, etc.), produce a number of somatic changes conjointly as a syndrome. Prominent among these are the involution of the thymicolymphatic apparatus, the appearance of gastrointestinal ulcers and the enlargement of the adrenal cortex (with discharge of its hormones, lipids and ascorbic acid).

(2) Some manifestations of this syndrome, especially the adrenal-cortical changes, proved to be useful. There is an increased corticoid~-hormone production, as judged by urinary bioassays; this helps adaptation since adrenalectomized animals are very inefficient in adapting themselves to a change, or in maintaining an already acquired adaptation, unless they receive corticoid substitution-therapy.

(3) Non-specific stress (e.g., exposure to cold, protein intoxication) can cause malignant nephrosclerosis, hypertension, and hyalinization with inflammatory changes in the arteries and in the hearts of experimental animals. Some of the changes so produced resemble those characteristic of acute rheumatic fever or of allergic tissue reactions.Let us now review the principal theories and thoughts derived from observations concerning the general-adaptation-syndrome.

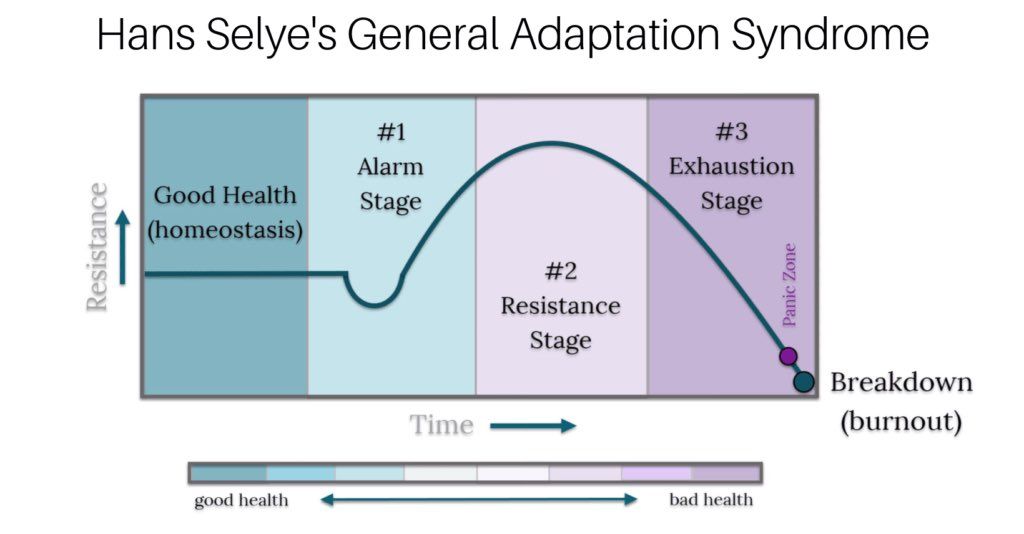

(1) In addition to many specific defense-reactions (e.g., maintenance of a constant body temperature, osmotic pressure, blood-pressure) there is an integrated syndrome of closely interrelated adaptive reactions to non-specific stress itself; this has been termed the “General-Adaptation-Syndrome" (G-A-S).

(2) The G-A-S does not merely represent a transitory “emergency” adjustment to changes in the environment, but is an adaptive reaction, which comprises the “learning” of defense against future exposure to stress, and helps to maintain a state of adaptation once this is acquired.

(3) The process of adaptation may itself become the immediate cause of diseases, namely of derangements due to maladaptation (hypo-, hyper- or dysadaptation). Among these are some of the most common fatal diseases of man, such as the hypertensive, the “rheumatic’’ and the “degenerative” or “wear-and-tear’ diseases of old age; the psychosomatic syndromes probably also belong to this group.

(4) In the G-A-S the manifestations of passive non-specific damage are intricately intermixed with those of active defense to it.Alarm

The alarm-reaction (A-R) is defined as the sum of all non-specific phenomena elicited by sudden exposure to stimuli, which affect large portions of the body and to which the organism is quantitatively or qualitatively not adapted. Some of these phenomena are merely passive and represent signs of damage or “shock”; others are manifestations of active defense against damage. In the event of moderately severe systemic stress, from which recovery is possible, the signs of injury usually precede the appearance of defense-phenomena. The alarm-reaction may, therefore, be subdivided in turn into two more or less distinct phases:

Shock

(1) The phase of shock. This is characterized by: hypothermia, hypotension, depression of the nervous system, decrease in muscular tone, hemoconcentration, deranged capillary and cell-membrane permeability, generalized tissue breakdown (‘catabolic impulse’), hypochloremia, hyperkalemia, acidosis, a transitory rise followed by a decrease in blood-sugar, leucopenia followed by leucocytosis, eosinopenia and acute gastrointestinal erosions. A discharge of adrenaline, corticotrophin and corticoids (with the secondary metabolic and organ-changes caused by these hormones) are early defense-reactions, which begin during the shock-phase but are actually characteristic of counter-shock. The shock-phase may vary from a few minutes to about 24 hours, depending upon the intensity of the damage inflicted, but (unless death ensues), it is always followed by the counter-shock phase.

There is no satisfactory definition of shock. In most cases one or the other sign of the shock-syndrome was singled out as its basic feature and the condition was then defined as one characterized by that manifestation (e.g., hypothermia, hypotension, hemoconcentration, capillary permeability, depression of the nervous system). Such definitions are not satisfactory because under certain conditions any one of the so-called ‘‘characteristic’’ signs may be manifest, although there is no shock, and conversely, shock may develop in the absence of one or the other of these signs.

We therefore prefer to consider shock as a condition of suddenly developing, intense, systemic (general) damage. Although this definition is not very instructive, it is necessarily correct since it merely represents a brief outline of those essential phenomena which induced physicians to coin the term. Shock is always a rapidly developing condition; damage caused by chronic ailments cannot be thus described. The term also implies that the damage is systemic (general); localized lesions, no matter how severe, are not designated as shock, unless they secondarily lead to generalized damage.

Counter-shock

(2) The phase of counter-shock. This phase is characterized by phenomena of defense against shock. There is an enlargement of the adrenal cortex with signs of increased activity, acute involution of the thymico-lymphatic apparatus and generally speaking, the reversal of most of the changes seen during the shock phase (e.g., a rise in blood-pressure, hyperchloremia, hyperglycemia, rise in blood volume, alkalosis, increased diuresis and often hyperthermia). These changes are not only synchronous with the stimulation of adrenalcortical activity but largely dependent upon the discharge of corticoids into the blood. Counter-shock phenomena may explain cases in which a distinct period of “primary shock’’ was followed by ‘‘secondary shock’ after an intermediate stage of relative well-being. It is possible that here the intermediate shock-free period is merely the equivalent of the counter-shock phase, which cannot be maintained (cf. ‘exhaustion’ below) and gives way to fatal shock.

The counter-shock phase of the A-R represents a transition to the stage of resistance (see below) and imperceptibly merges into the latter in the event of chronic exposure. The principal reason for recognizing this as a distinct phase of the G-A-S is that under the impact of short, sublethal, systemic stresses, some manifestations of the initial shock phase are eventually reversed although, in the absence of repeated exposure, a stage of resistance cannot become manifest.

Resistance

The stage of resistance represents the sum of all non-specific systemic reactions elicited by prolonged exposure to stimuli to which the organism has acquired adaptation. It is mainly characterized by an increased resistance to the particular stressor agent to which the body has been exposed and a decreased resistance to other stimuli. Thus the impression is gained that during the stage of resistance, adaptation to one agent is acquired ‘‘at the expense of” resistance to other agents.

Most of the morphologic and biochemical changes of the A-R disappear during the stage of resistance and indeed in some instances the direction of the deviations from the normal is reversed (e.g., hypochloremia during the A-R, hyperchloremia during the stage of resistance; loss of lipids from the adrenal cortex during the A-R, deposition of lipids into this gland during the stage of resistance).

Exhaustion

The stage of exhaustion represents the sum of all non-specific systemic reactions which ultimately develop as a result of prolonged over-exposure to stimuli to which adaptation has been developed but could no longer be maintained.

It was found that even a perfectly adapted organism cannot indefinitely maintain itself in the stage of resistance. If exposure to abnormal conditions continues, adaptation wears out and many lesions characteristic of the A-R (e.g., involution of the thymico-lymphatic system, loss of adrenal-lipids, gastrointestinal ulcers) reappear as a stage of exhaustion develops and further resistance becomes impossible.

Conclusion

The general-adaptation-syndrome (G-A-S) is the sum of all non-specific systemic reactions of the body which ensue upon long-continued exposure to systemic stress. One of the most fundamental observations in connection with the G-A-S was the finding that many of the morphologic, functional and biochemical changes elicited by various systemic stressor agents are essentially the same irrespective of the specific nature of the eliciting stimulus. We coined the inclusive term ‘‘general-adaptation-syndrome” to denote the whole response of which the A-R, the stage of resistance, and the stage of exhaustion are merely three successive phases.

The reaction is general; it is elicited only by those stresses which are generalized (in that they affect large portions of the body) and it in turn evokes generalized, systemic defense phenomena.

The reaction is adaptive; it helps the acquisition and maintenance of a state of inurement.

The reaction is a syndrome; its individual manifestations are co-ordinated and partly even inter-dependent.

The G-A-S must be distinguished from the specific adaptive reactions, such as the hypertrophy of the musculature after prolonged exercise, the allergic or immunologic phenomena elicited by certain foreign proteins or micro-organisms, etc. ‘These latter responses are not evoked by systemic stress. They usually endow the body with a great deal of resistance against one particular agent (that to which it had previously been exposed), but, both the manifestations of such specific adaptive reactions and the resistance which they confer upon the organism are limited to the agent which elicited them. Perhaps because historically the A-R was the first to be described, or because of its striking name, it received the greatest attention in the literature pertaining to the G-A-S. Indeed, some workers fail to distinguish clearly between the A-R and the G-A-S as a whole. We wish to re-emphasize, therefore, that the former is merely the first stage of the latter and that if an organism is continuously subjected to severe systemic stress, the resulting G-A-S always evolves in three successive stages, namely, first ‘‘the alarm reaction”, then the “stage of resistance" and finally the "stage of exhaustion”.