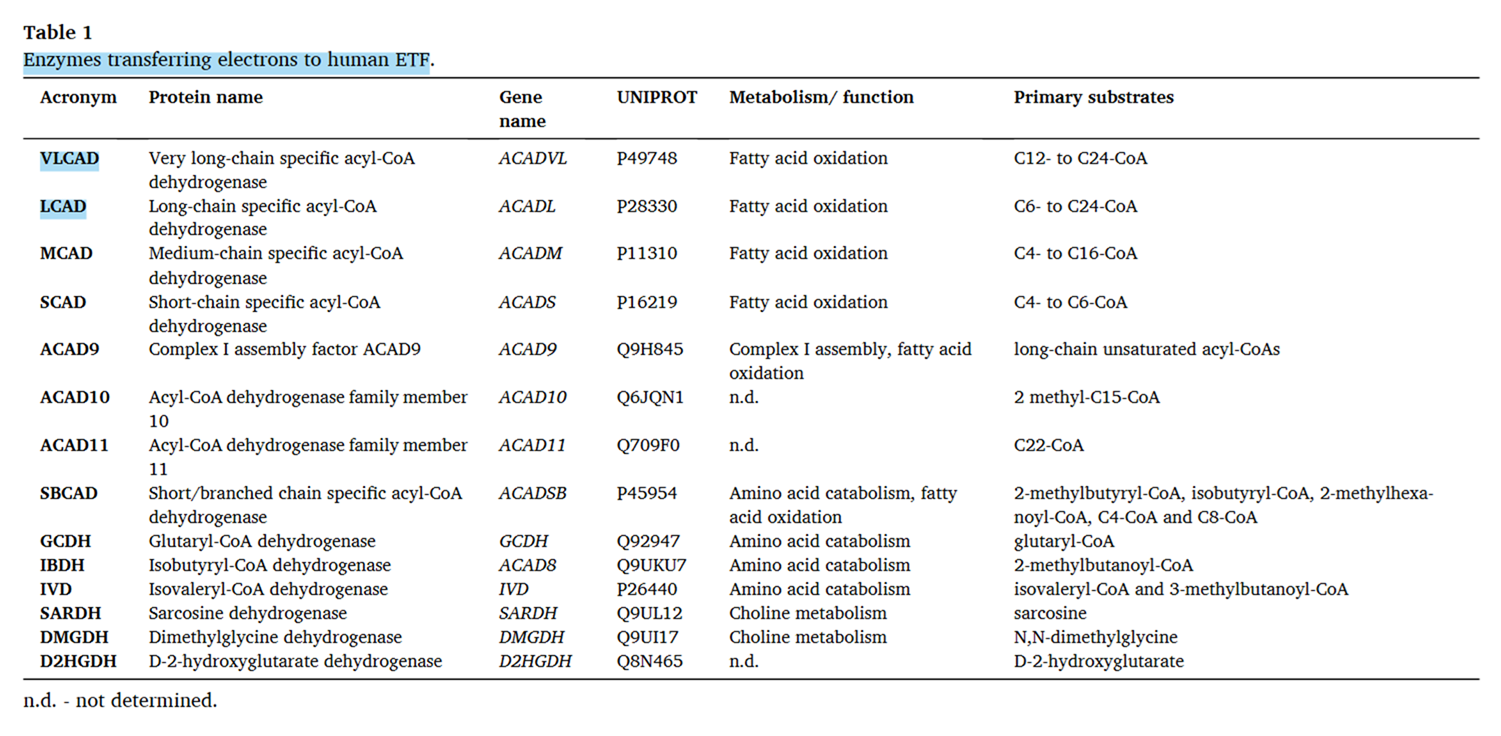

Toward a Better Understanding of Reactive Oxygen Species

-

I feel bad for anyone trying to produce meaningful material that demands effort these days, but anything more elaborate ends up being attributed to bots either way, so let's at least embrace efficiency.

For instance, yesterday I authored a book titled:

- "A Bioenergetic View of Biological Energy: ATPizing All Problems Off"

Not willing to spend another 30 minutes, I went for a day of rest with something less draining, this time using a single prompt:

Good afternoon. Just dump to me content for a post that may be titled "Toward a Better Understanding of Reactive Oxygen Species". Include language vices to personalize paragraphs, embarassing typos for humanization ('flavorproteins'), and placeholders for filler images to not bore readers. Use em-dashes without overindulging—it's the new avoidance. People cheat on you, but I've been loyal to my one and only model, so give it a special attention for that.

The result was fine for a 2-minute prompt, but it's what we have for today.

Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide as the main reactive oxygen species

(Bear with the automatic blue headings by remembering that you consume poison A on a regular basis, so you must be used to insults.)

Molecular oxygen (O₂) is more soluble in lipids than in water, so it concentrates in fatty regions around enzymes, where they cluster for efficient electron transfer. Cytochrome c oxidase (Complex IV) in mitochondria is one such enzyme, and it performs cellular respiration in the strict sense: O₂ consumption at the cellular level as it reacts with electrons (e⁻) under tight control.

Complete oxygen reduction ⟶ Water

- O₂ + 4e⁻ + (4H⁺) ⟶ 2H₂O

- ½O₂ + 2e⁻ + (2H⁺) ⟶ H₂O — simplified to reflect the pair of electrons transferred by dehydrogenases

Partial oxygen reduction ⟶ Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

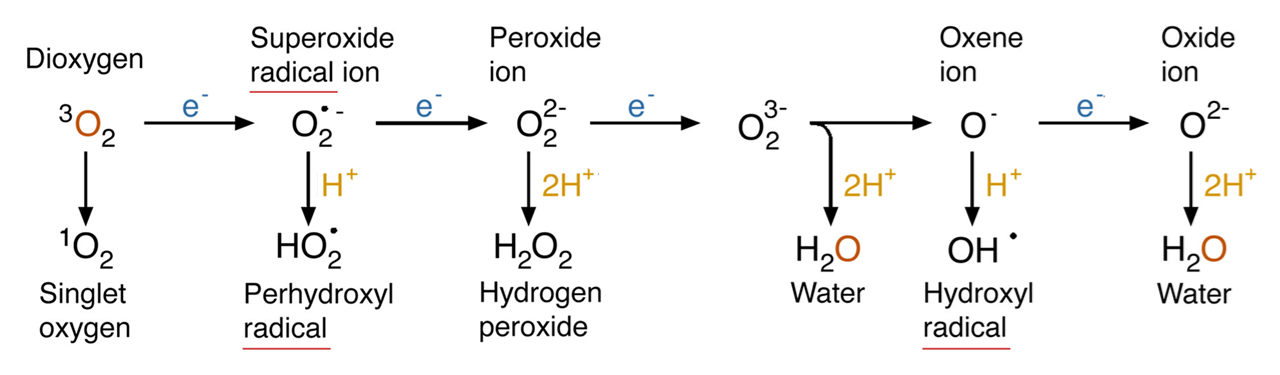

When O₂ receives fewer than 4 electrons, it's only partially reduced, and the specific ROS produced depends on a combination of electrons (top row) and protons (bottom row) shown in the overall changes below:

⠀(10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701)Oxygen atoms from inhaled O₂ can end up as water through ROS, independently of Complex IV. This represents complete O₂ reduction to water, but in separate steps.

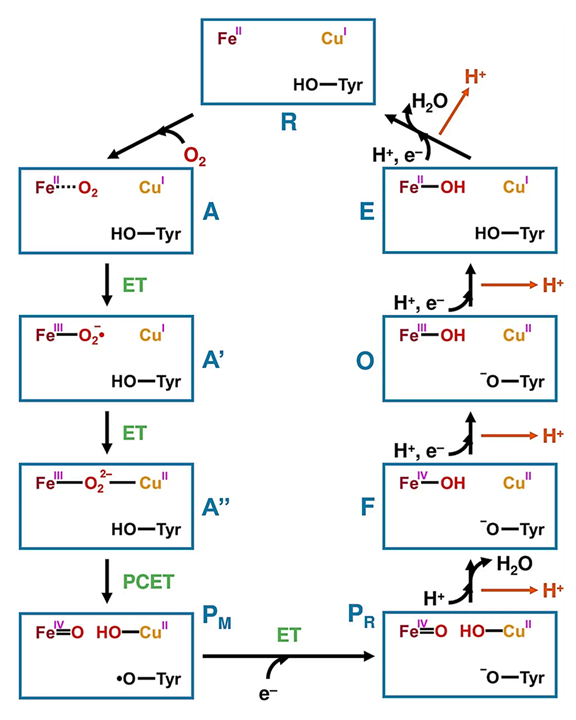

In Complex IV, complete O₂ reduction occurs through a sequence of fast reactions that generate intermediates containing oxygen species analogous to those above.

⠀(10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2023.112367)Despite being an oxygen- and electron-rich microenvironment with iron and copper nearby, the coordinated reactions take place in a dedicated cavity that isolates intermediates and normally prevents premature release of oxygen species, explaining the insignificant ROS production from Complex IV itself.

Superoxide (O₂•⁻) and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) are the main products of incomplete O₂ reduction in cells.

- "•" → symbol for unpaired or lone electron (radical)

- "⁻" → symbol for negatively-charged molecule (more electrons than protons)

The uncharged form of superoxide (HO₂• ⇄ O₂•⁻ + H⁺) is more lipid-soluble like H₂O₂, but the relatively high pH in cells doesn't favor its occurrence, so only a minority of superoxide exists this way.

While H₂O₂ often derives from enzymatic conversion of O₂•⁻, some reactions release H₂O₂ directly. Both can lead to the hydroxyl radical—the most reactive of the common ROS.

Superoxide radical ion (O₂•⁻) Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) Hydroxyl radical (•OH) Radical?  ️

️

️

️Uncharged?  ️

️ ️

️ ️️

️️Readily crosses compartments?

️

️

Relatively stable?

️

️

Approximate half-life 10⁻⁶ s 10⁻³ s 10⁻⁷ s Main targets Fe-S clusters, NO -SH (thiols), Fe/Cu The NA, PUFAs, proteins, etc Because H₂O₂ is uncharged (neutral), diffuses readily across compartments, and is relatively stable, its emission rate serves as a convenient proxy for internal ROS production. However, proteins can also play a role in H₂O₂ movement between compartments, making the flux less passive and more regulated than it seems.

ROS from electron leakage usually originate with superoxide:

- O₂ + e⁻ ⟶ O₂•⁻

Once released in cells, superoxides are quickly metabolized by the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD):

⠀(10.1134/S0006297915050028)It may surprise you, but superoxide dismutase dismutates superoxide:

- O₂•⁻ + O₂•⁻ + H⁺ + H⁺ ⟶ H₂O₂ + O₂

Mitochondrial SOD depends on Mn to function as a dismutase. When Mn is scarce and Fe is abundant, SOD may incorporate Fe instead, turning this antioxidant dismutase into a prooxidant peroxidase.

The fast dismutation of O₂•⁻ to generate the more stable H₂O₂ explains its prevalence in mitochondria. This conversion also happens non-enzymatically, but at a much lower rate and becomes significant only when SOD activity is insufficient.

Each H₂O₂ molecule detected therefore reflects the loss of two electrons to O₂, whether it's produced directly or indirectly from separate one-electron leaks (superoxide dismutation). Random values to illustrate:

Electron leak from detected H₂O₂ rate

- 1 nmol H₂O₂/min/mg protein *

- × 2e⁻/H₂O₂ = 2 nmol e⁻/min/mg protein

Electron consumption in respiration from O₂ consumption rate

- 50 nmol O₂/min/mg protein *

- × 4e⁻/O₂ = 200 nmol e⁻/min/mg protein

*Both are reported in experiments.

Fraction of electrons (e⁻) diverted to ROS

- (Rate of e⁻ leaked) ÷ (Rate of e⁻ consumed in respiration)

- 2 nmol ÷ 200 nmol = 0.01 = 1%

This way, a high percentage (such as 2%) may result from excessive ROS production, but it may also result from low O₂ consumption, giving a false impression of ROS overexposure. That's why relying on simplified fractions alone can be misleading.

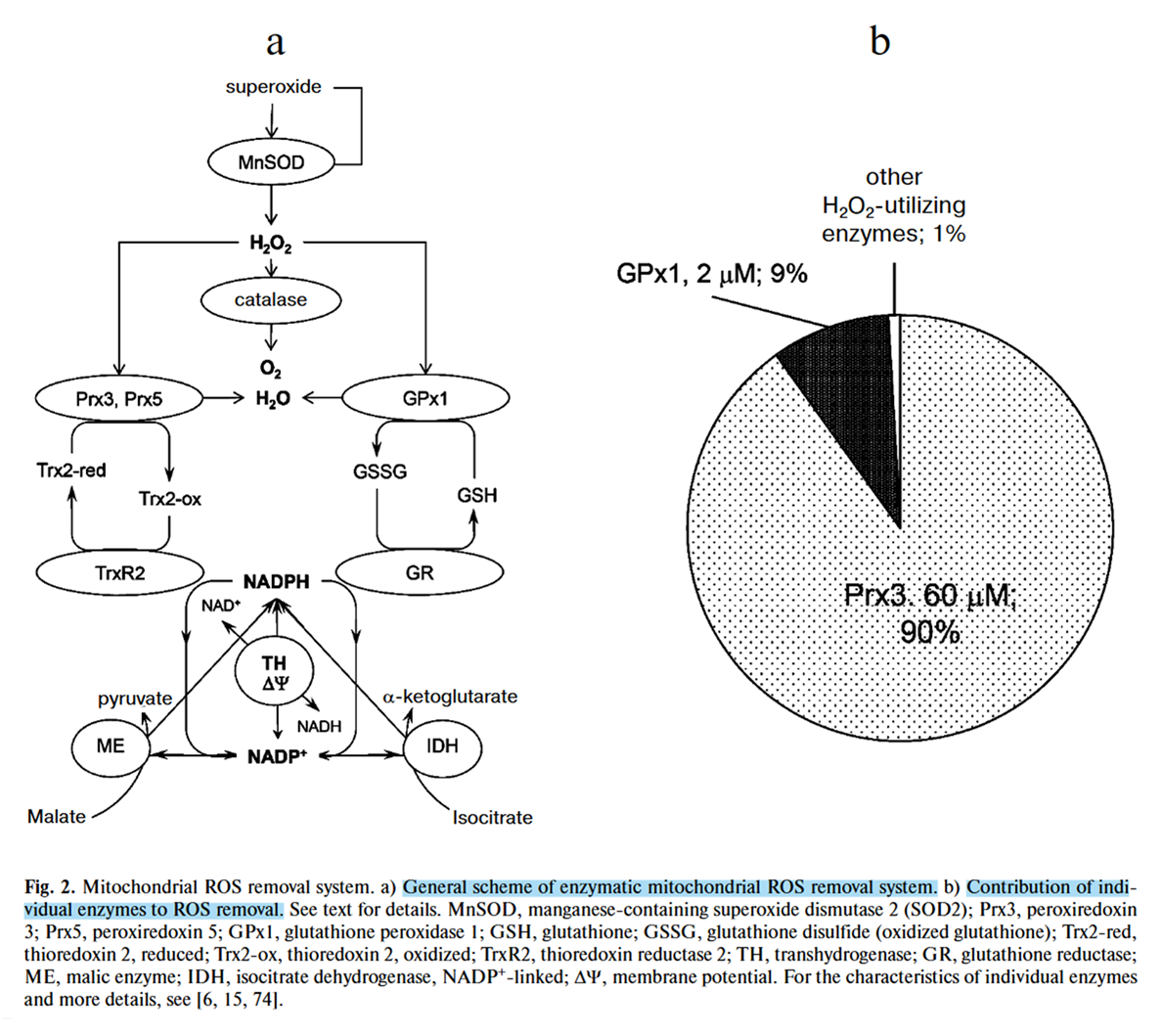

The enzymatic fates for H₂O₂ within a compartment are more diverse than those of O₂•⁻, for example:

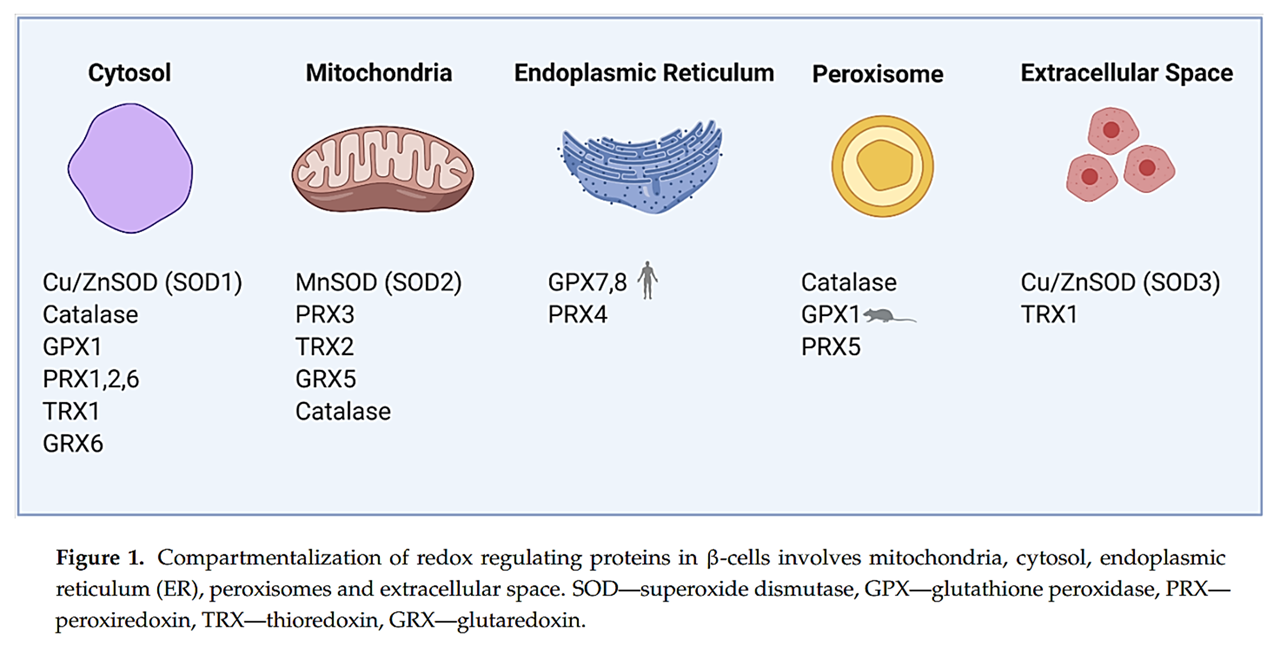

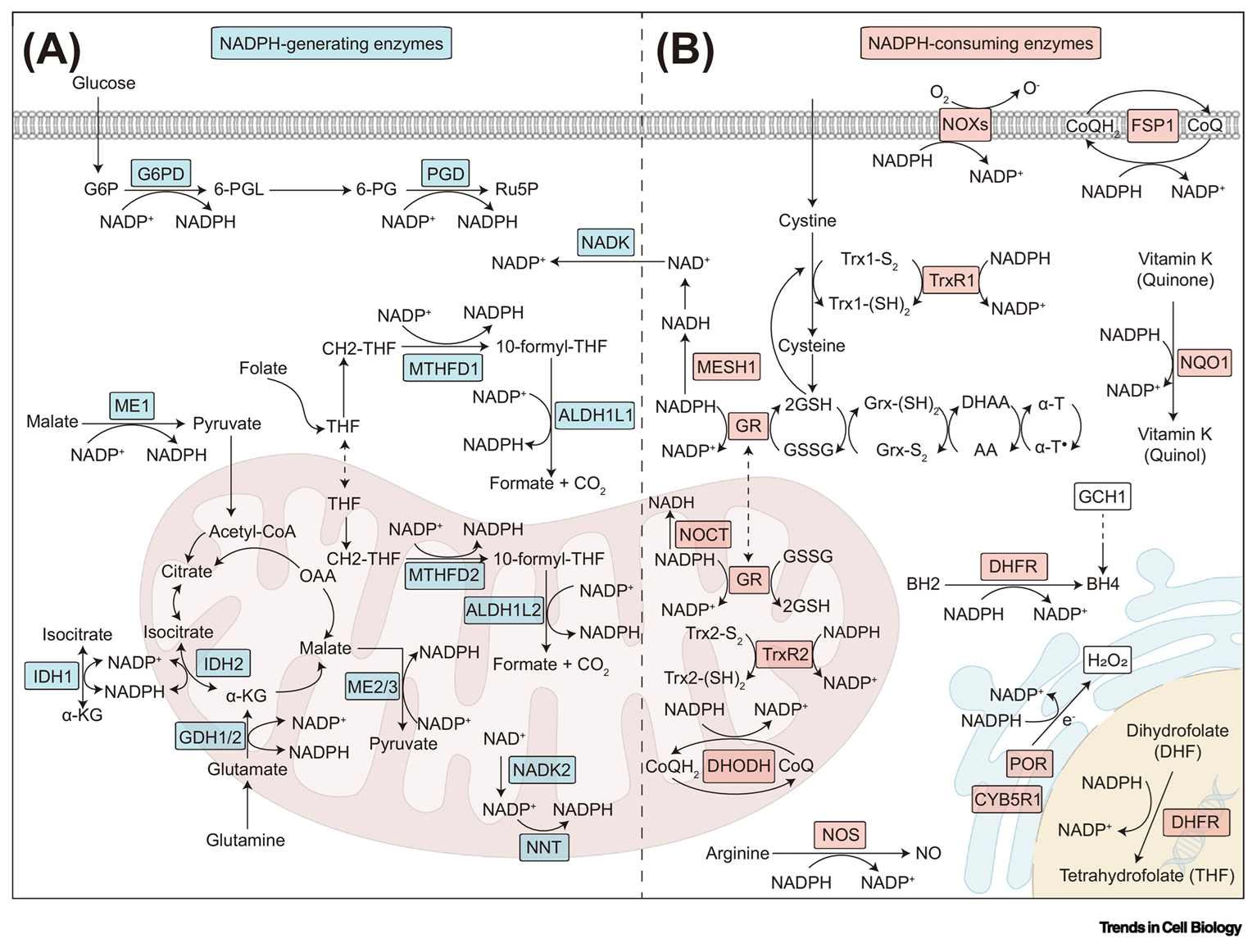

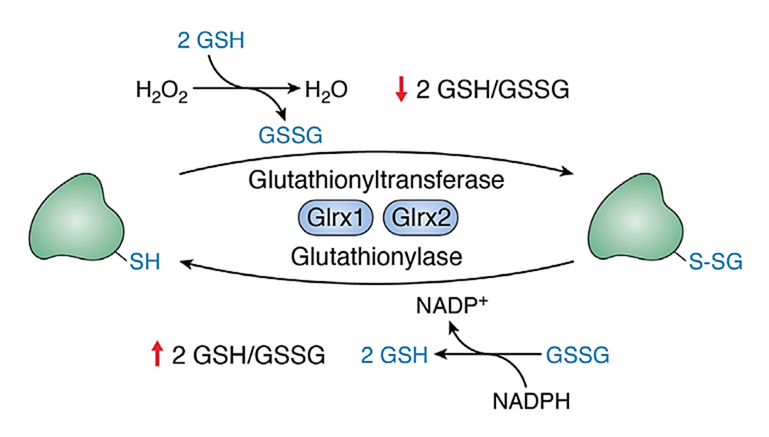

⠀(10.3390/antiox10040526)The main antioxidant systems (excluding catalase) neutralize H₂O₂ by exploiting its reactivity with thiols, and function based on this principle:

- H₂O₂ + NADPH + H⁺ ⟶ 2H₂O + NADP⁺

NADPH donates the 2 remaining electrons needed to complete the 4-electron reduction of O₂ into 2 water molecules.

(Catalase works as a hydrogen peroxide dismutase: 2H₂O₂ ⟶ 2H₂O + O₂, and functions without the need for NADPH.)

As a side note, H₂O₂ production and neutralization consume 4 H⁺, whose removal from the surroundings causes slight alkalinization.

- O₂ (+ 2H⁺) → H₂O₂ (+ 2H⁺) → 2H₂O

To keep antioxidant systems functional, the following enzymes regenerate NADPH:

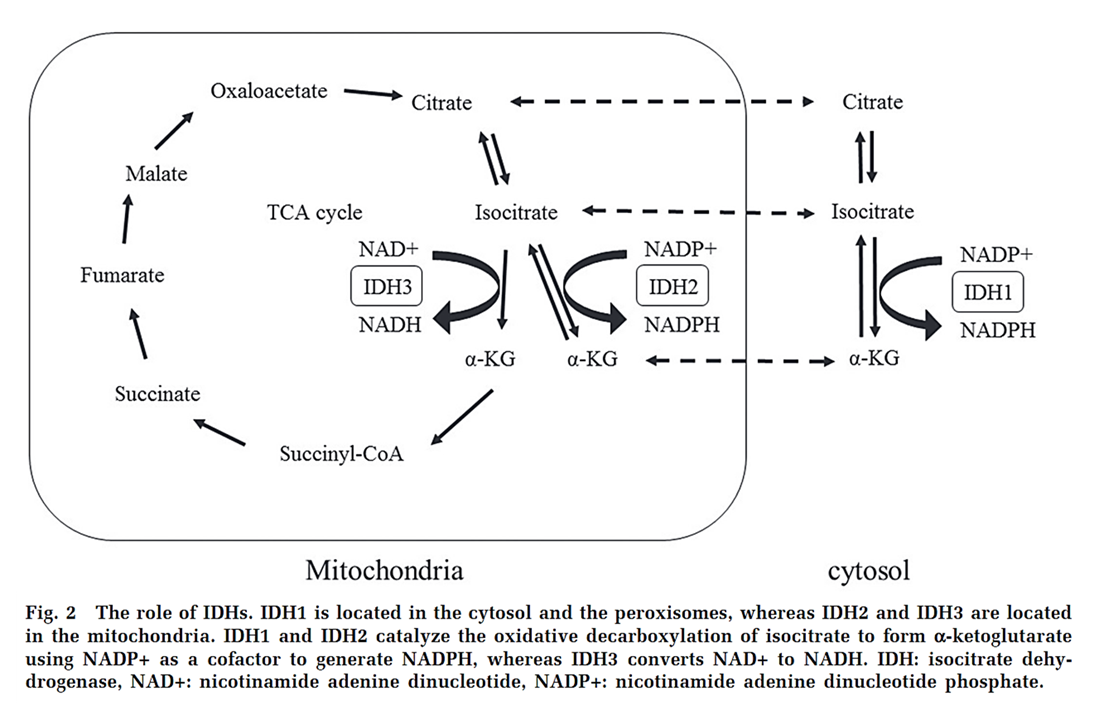

Enzyme Electron donor (substrate) Cytosol G6PD Glucose-6-phosphate PGD 6-Phosphogluconate ME1 Malate IDH1 Isocitrate MTHFD1 5,10-CH₂-tetrahydrofolate ALDH1L1 10-CHO-tetrahydrofolate {NADK1*} - Mitochondria NNT NADH ME2/3 Malate IDH2 Isocitrate GDH2 Glutamate MTHFD2L 5,10-CH₂-tetrahydrofolate ALDH1L2 10-CHO-tetrahydrofolate {NADK2*} - * NAD + ATP -{NADK}→ NADP + ADP

(Enzyme numbers tend to rise as the compartment in which the isoform occurs gets less ancient.

For example, ACS1 is mitochondrial and ACS2 cytosolic. Wait... Never mind.)

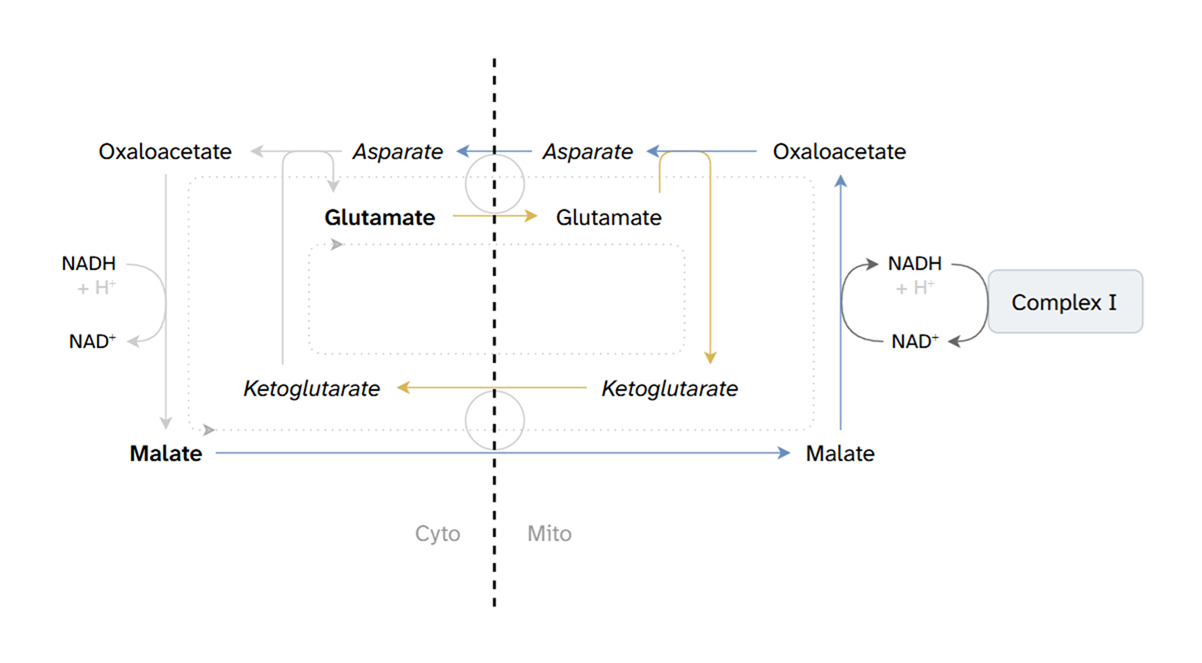

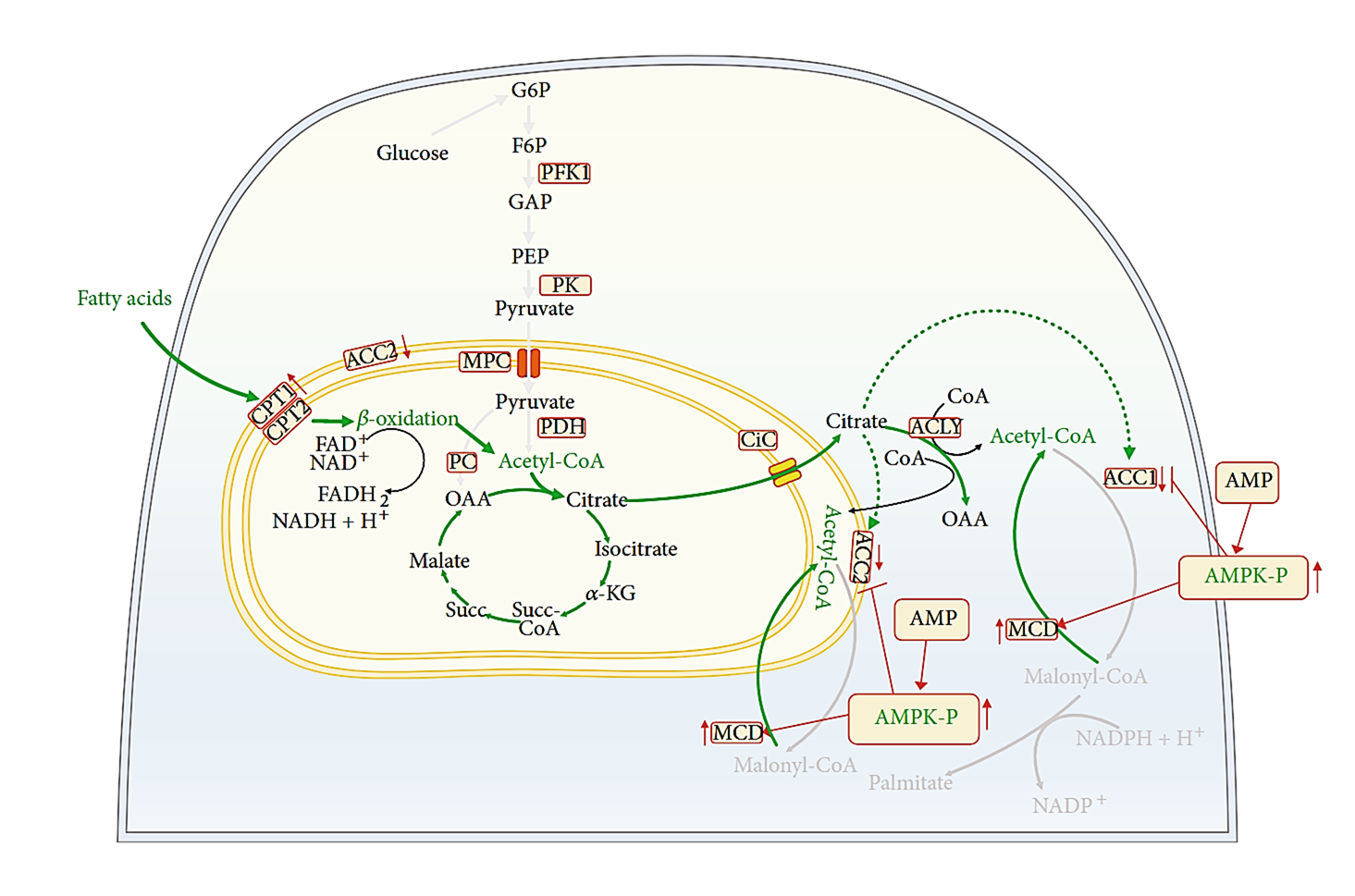

⠀(10.1016/j.tcb.2023.07.003)For substrates whose oxidation is mitochondrial (such as common fatty acids), ROS is generated locally and a portion is neutralized before leaving the compartment, limiting external exposure. Nevertheless, mitochondria can export electron donors to regenerate NADPH in the cytosol, ensuring sufficiency even if the electron source is metabolized elsewhere, as illustrated by the shuttle shown in the previous figure and highlighted below.

⠀(10.2176/nmc.ra.2015-0322)An increase in the disulfide/thiol (–SS–/–SH) ratio signals decreased antioxidative capacity. Some disulfide molecules then target specific thiol residues on enzymes (such as PDHc, KGDHc, Complex I, etc.), which reversibly deactivates them. This can prevent these enzymes from amplifying ROS production until antioxidant defenses are restored.

⠀(10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105399)When one NADPH-regenerating method fails, another can partially compensate, keeping antioxidant systems and ROS levels stable.

In addition to regulating enzymes, hydrogen peroxide (and superoxide) can also induce other beneficial effects. For example:

ROS that escape neutralization can encounter reactive metals (Fe or Cu), leading to the highly problematic hydroxyl radical (•OH).

Superoxide donates an electron to iron:

- O₂•⁻ + Fe³⁺ ⟶ O₂ + Fe²⁺

Electron-loaded iron donates its electron to hydrogen peroxide:

- Fe²⁺ + H₂O₂ ⟶ Fe³⁺ + •OH + OH⁻

The second reaction can occur directly if Fe²⁺ is already present, dispensing the first reaction involving superoxide. In essence:

O₂•⁻ ↷Fe²⁺ ↷ •OH ↷

That is when non-enzymatic antioxidants become most useful:

With this brief ROS overview, we now turn to their origins.

Cellular ROS comes in part from mitochondria

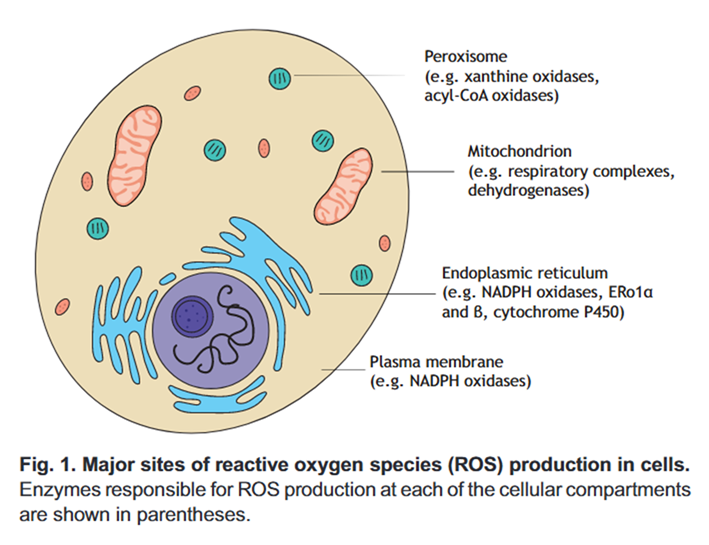

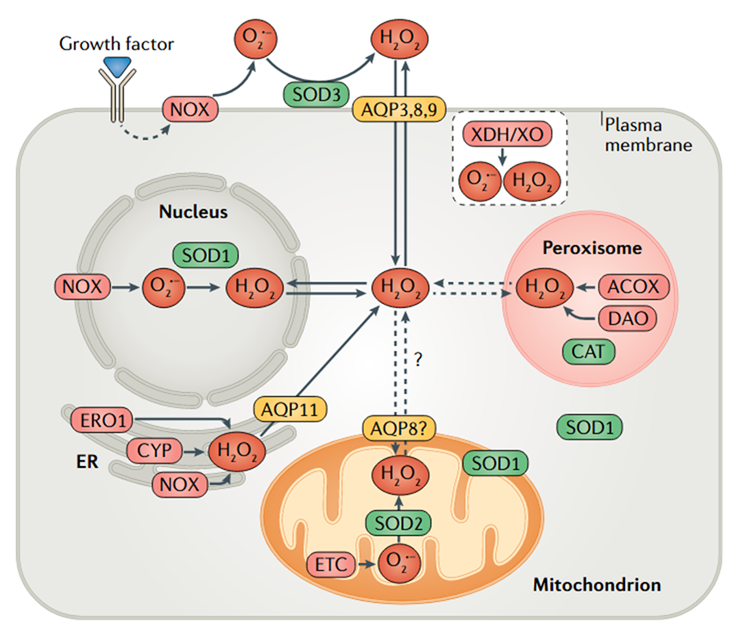

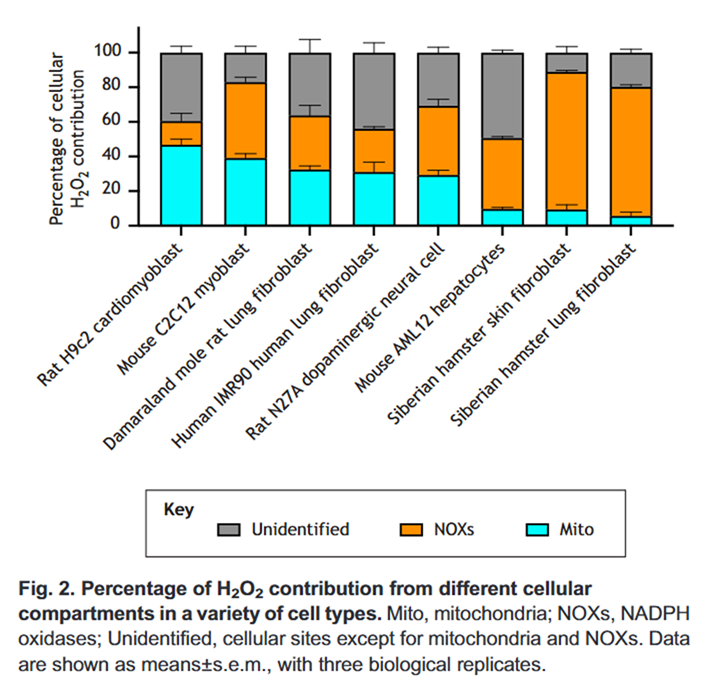

Mitochondria are central to nutrient oxidation and important ROS producers, but they aren't always the dominant source.

⠀(10.1242/jeb.221606)

⠀(10.1038/s41580-020-0230-3)

⠀(10.1242/jeb.221606)Mitochondria might even switch between a ROS source to a ROS sink under certain conditions.

Cellular ROS can arise in three ways, simplified as follows to contrast them:

- Incidental by-products of exogenous agents

- Intrinsic products of specific enzymes

- Incidental "by-products" of metabolic reactions

Exogenous agents (such as radiation and toxins) can directly generate ROS by destabilizing molecules, yielding species that readily lose electrons to oxygen. The present discussion, however, focuses on endogenous production that's not initiated by external triggers.

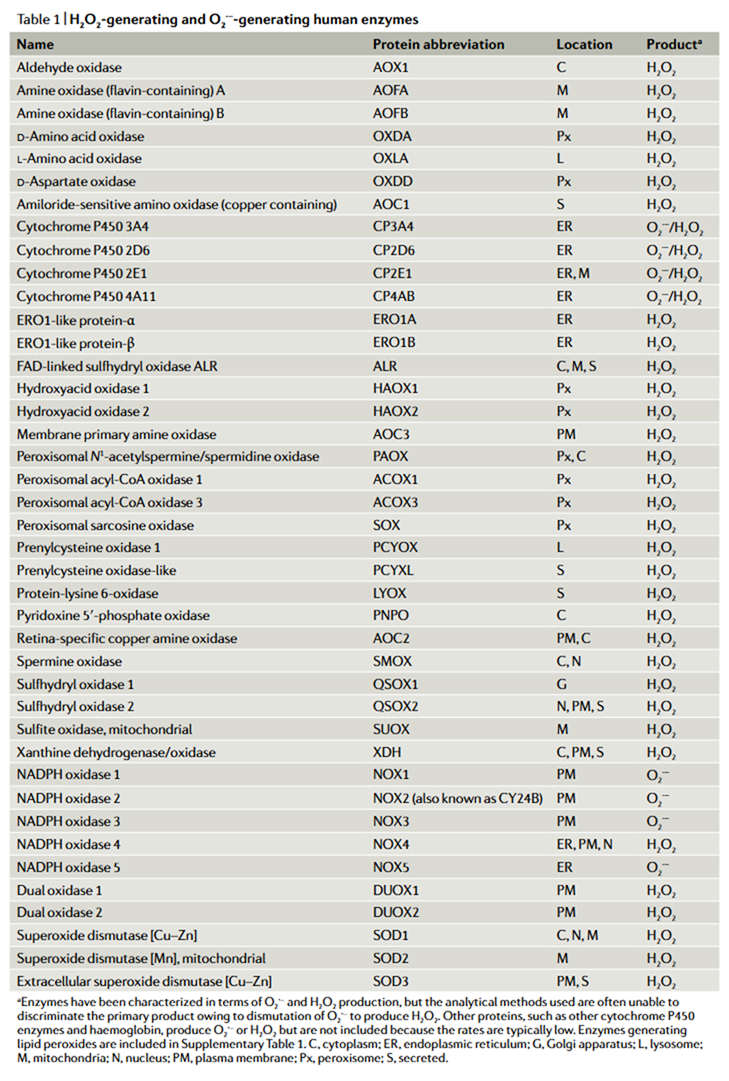

Certain enzymes release ROS as intrinsic products, appearing in their reaction equations, making the sources more predictable.

⠀(10.1038/s41580-020-0230-3)In contrast, when nutrients are oxidized for energy, many metabolic reactions produce incidental ROS from sources that are less consistent and harder to trace. The following sections try to bring some clarity to that.

Mitochondrial ROS sources during cellular respiration: beyond Complex I

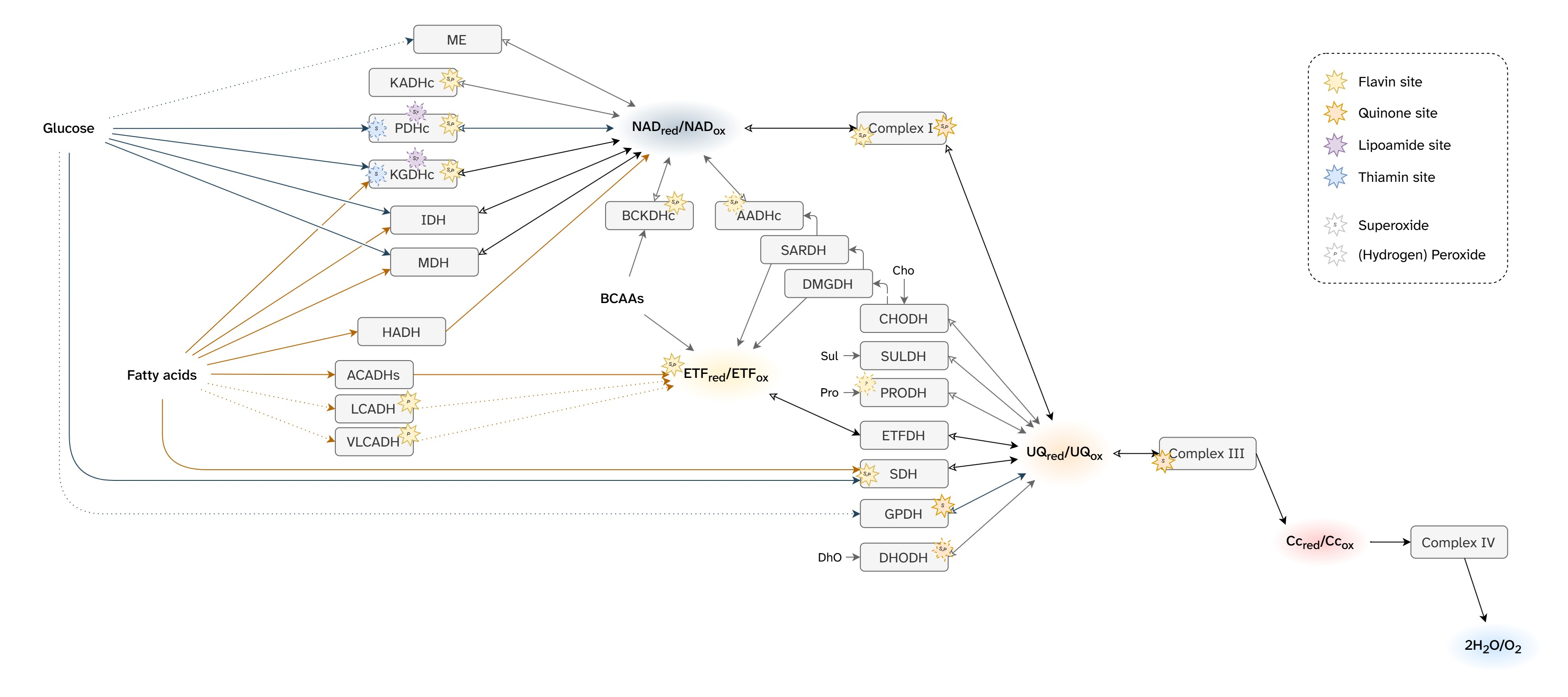

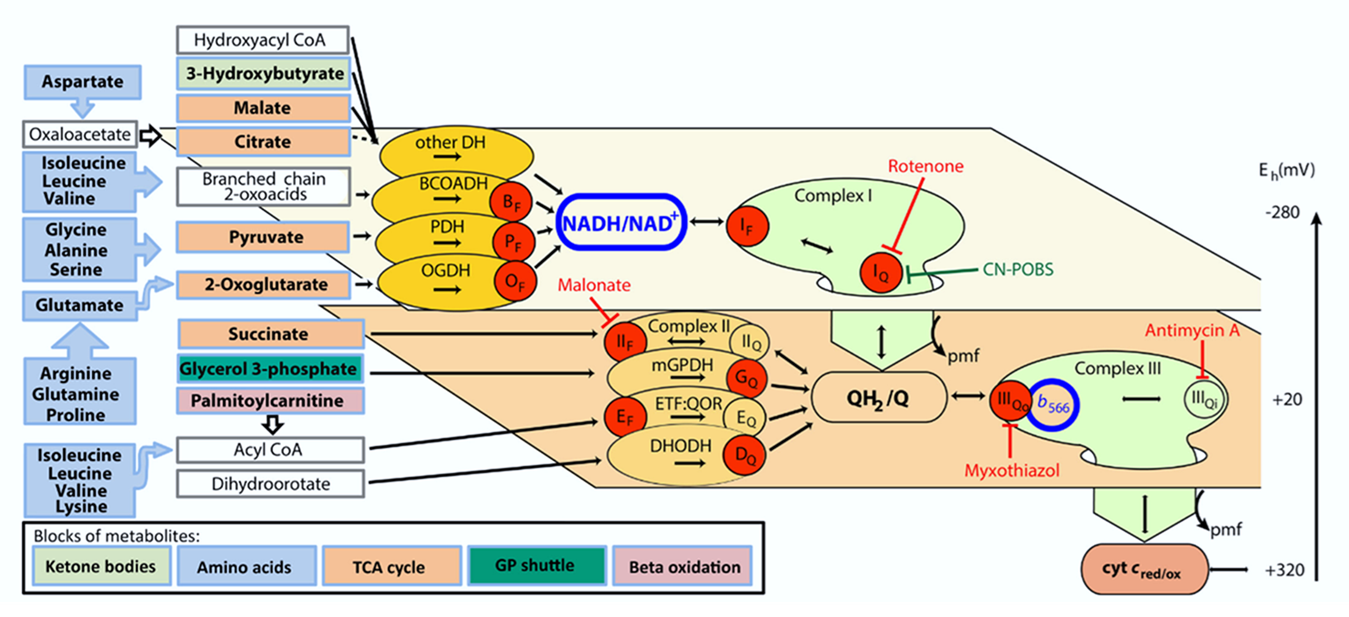

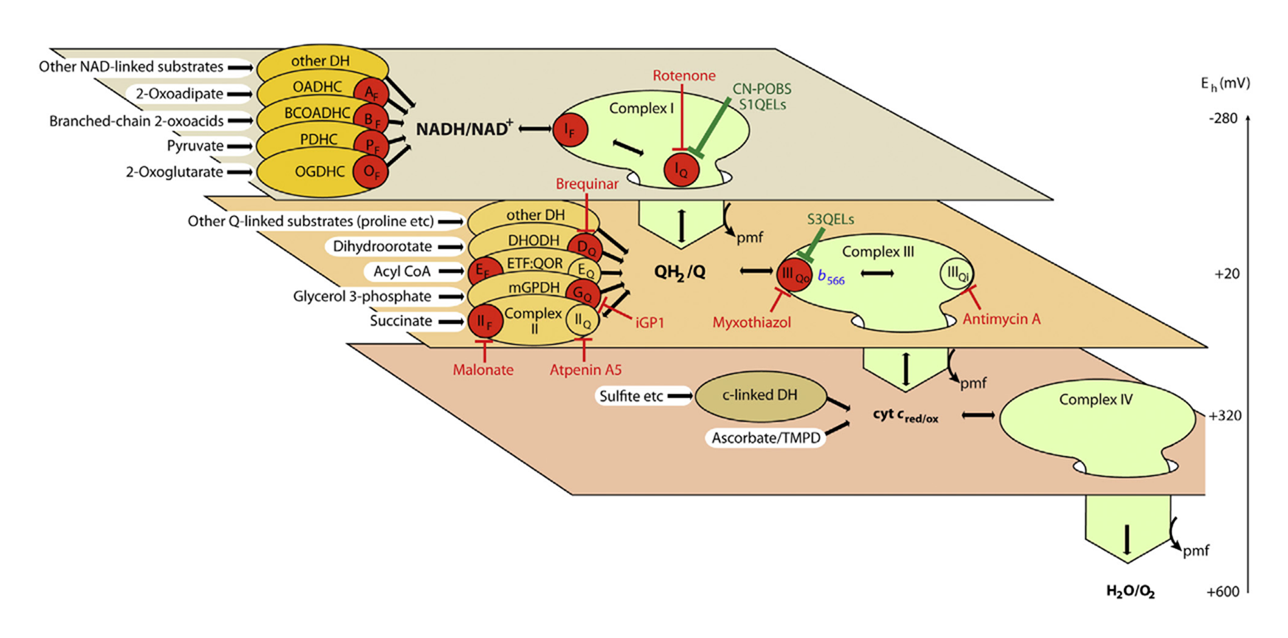

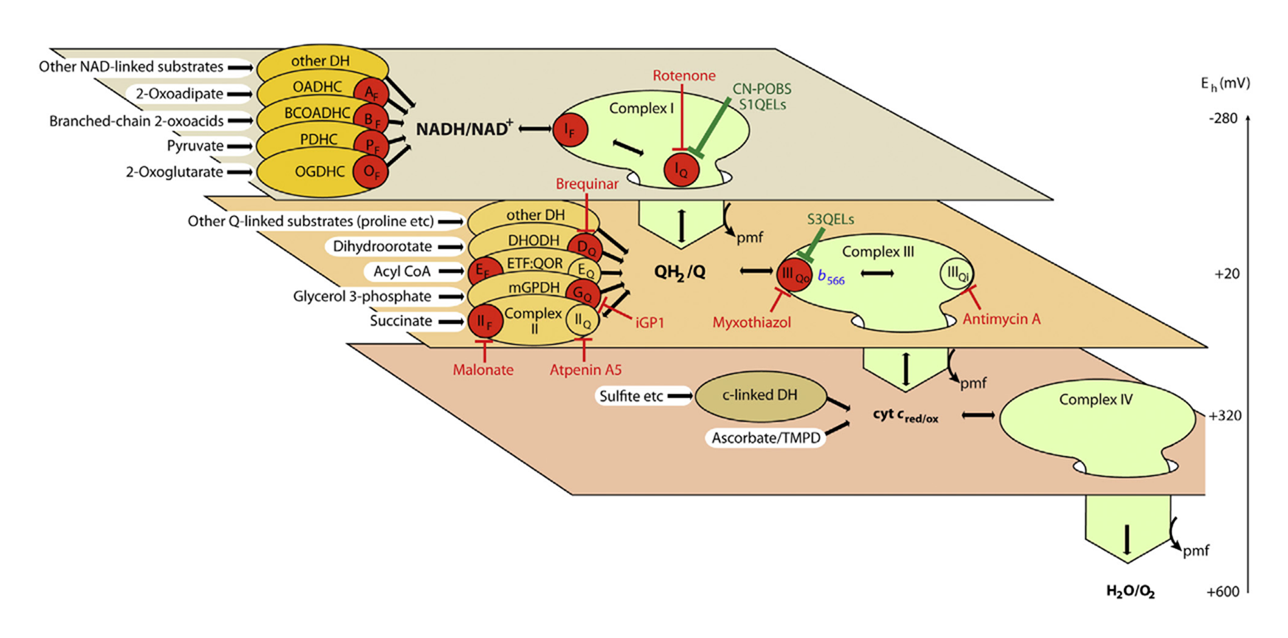

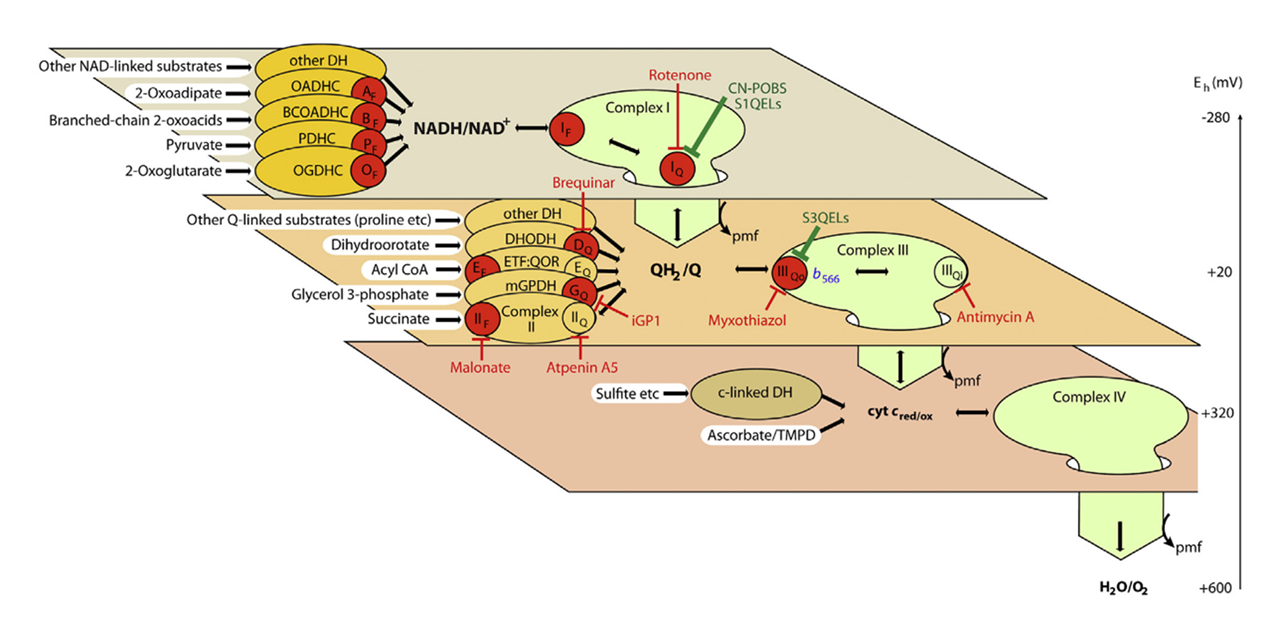

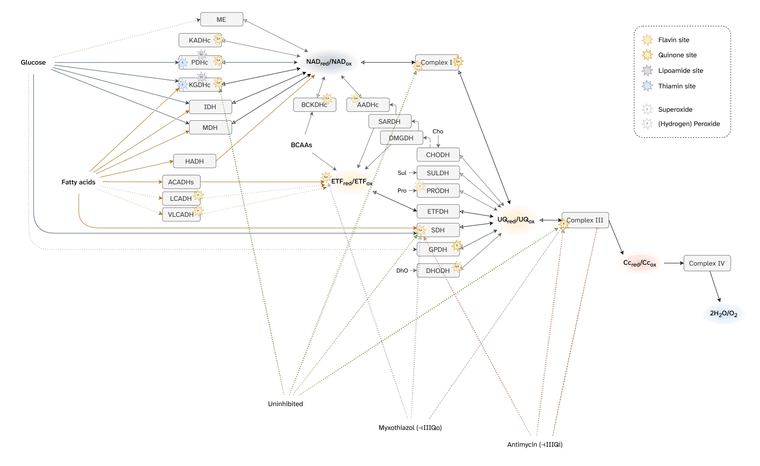

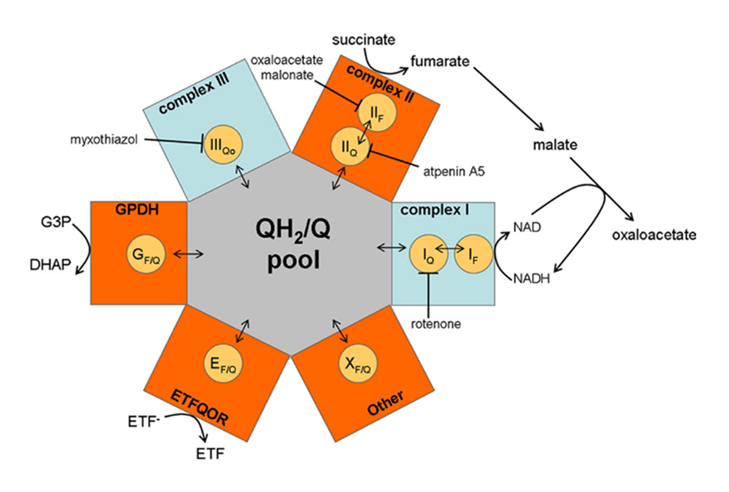

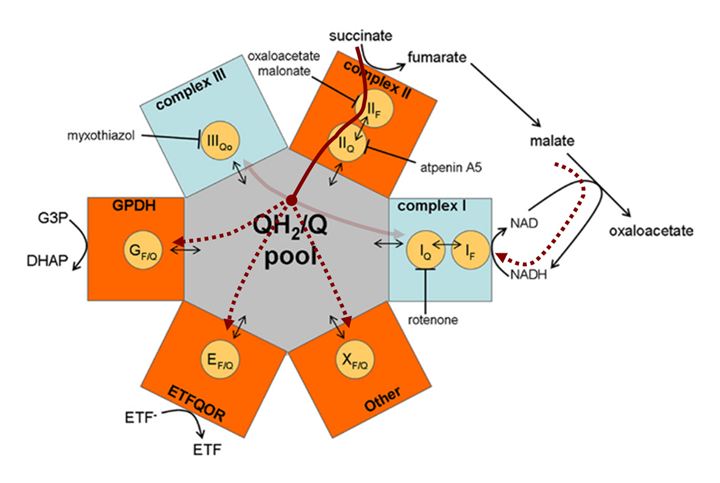

Martin Brand summarized mitochondrial ROS production from cellular respiration:

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001)

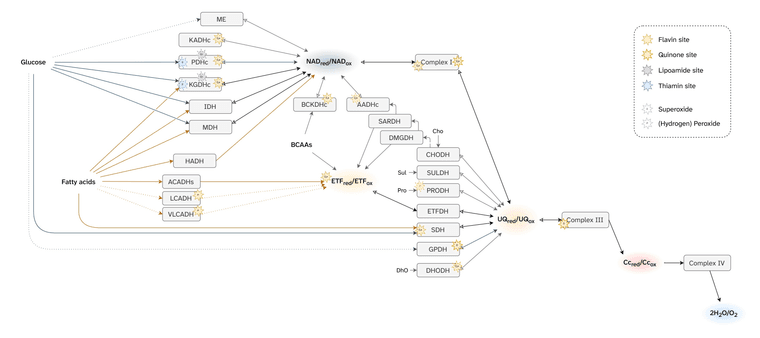

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M114.619072)The ellipses represent enzymes that can affect ROS production depending on the substrate being oxidized.

Red circles indicate that the enzyme directly contributes to ROS production. The label inside identifies the specific site within the enzyme or path. Subscripts in circles detail whether the site involves flavins or quinones.

- For example, PDHc has a red circle (ROS source) labeling its flavin site as origin ('Pf'). Abbreviations like that will appear often throughout the text.

Each plane groups components based on similarities of redox potentials ('isopotential grouping'). Each plane also contains a characteristic node: NAD, UQ, Cyt c. These are the pools of mobile electron carriers that connect enzymes, creating many possible alternative routes from a node.

After electrons pass through the respiratory complexes that use some of the energy for work (Complex I, III, and IV), they drop to a lower level, matching the redox potential of the next group. Complex IV concludes respiration and doesn't cause a further drop.

Proteins (or enzymes) that are not ROS producers can still influence production indirectly by modifying the availability of electrons at the susceptible sites. Moreover, some may interact with ROS ahead of dedicated enzymes. These proteins appeared earlier without red circles. For example:

- Oxidation of hydrogen sulfide remains a priority in mammalian cells and causes reverse electron transfer in colonocytes

- Sulfite oxidase activity of cytochrome c - Role of hydrogen peroxide

- Cytochrome c, an ideal antioxidant

- Effect of Cytochrome c on the Generation and Elimination of O₂•⁻ and H₂O₂ in Mitochondria

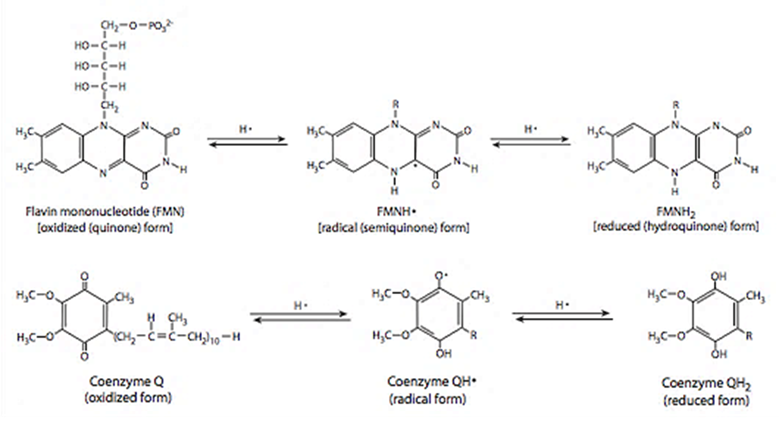

Flavins and quinones were the only specifiers (subscripts f or q) because both participate in one-electron reactions at contact sites with access to oxygen, making them especially prone to ROS production.

⠀(9780985226114)Of note, fatty acid oxidation is more dependent on flavins and quinones than glucose oxidation.

- ACADH (FAD) isoforms have different chain-length specificities, so the starting enzyme won't be responsible for completing all β-oxidation cycles. Instead, the fatty acid keeps getting transferred between ACADHs as it's shortened, each needing its own flavin ready for use.

- ETF (FAD) trapping between partner enzymes limits dispersion, yet it remains a mobile carrier that occurs in large excess over partners, again needing extra flavin.

- ETFDH (FAD) becomes an additional respiratory complex, although its flavin is protected from oxygen.

- KGDHc (FAD) and SDH (FAD) are needed more often because fatty acid oxidation has a greater dependence on the TCA cycle (exclusive reliance on it for decarboxylation).

- Complex I (FMN) may be engaged just as much, if not more frequently.

FMN 2:1 FAD — Fatty acids- FMN 6:3 FAD — Fatty acids

- FMN 5:1 FAD — Glucose

- Ubiquinone (UQ) cycling increases to transfer extra electrons in compensation for less ATP produced per electrons consumed.

- 6 FMN + 3 FAD → 9 UQ↺ — Fatty acids

- 5 FMN + 1 FAD → 6 UQ↺ — Glucose

⠀(Values above were for illustration.)

However, flavins and quinones are not the only electron leakers, and the number of mitochondrial ROS sources linked to cellular respiration keeps being revised:

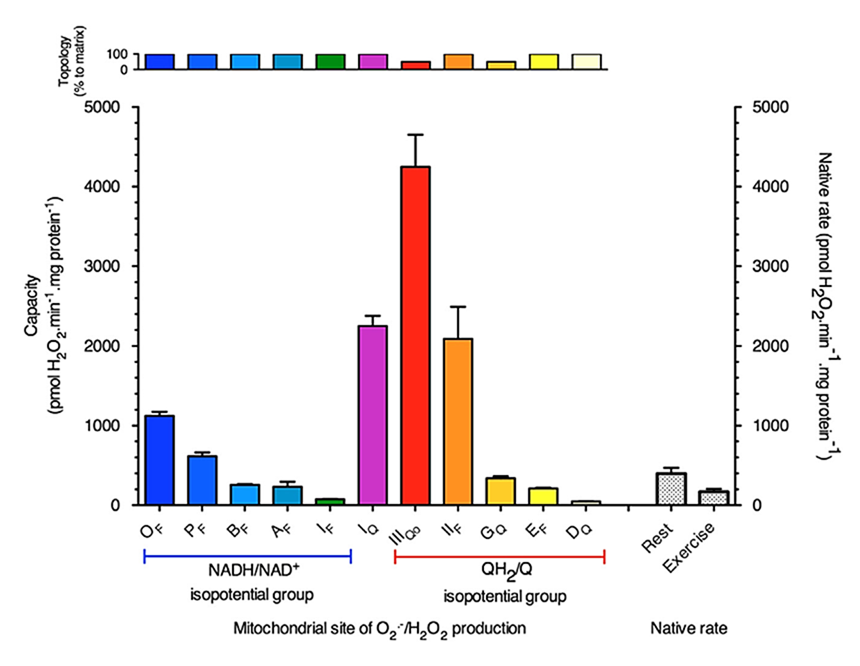

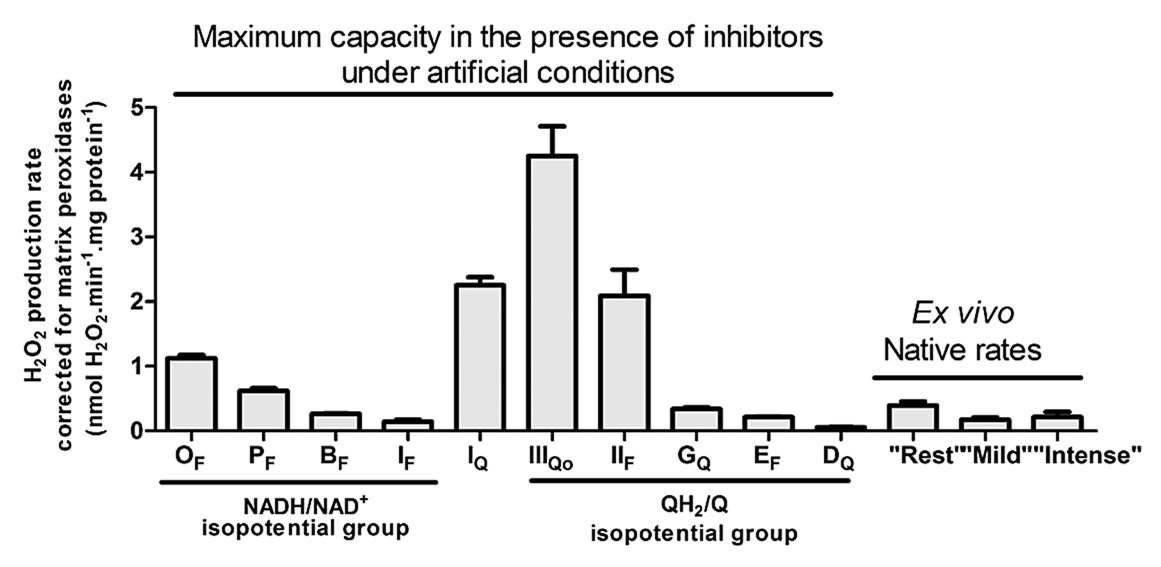

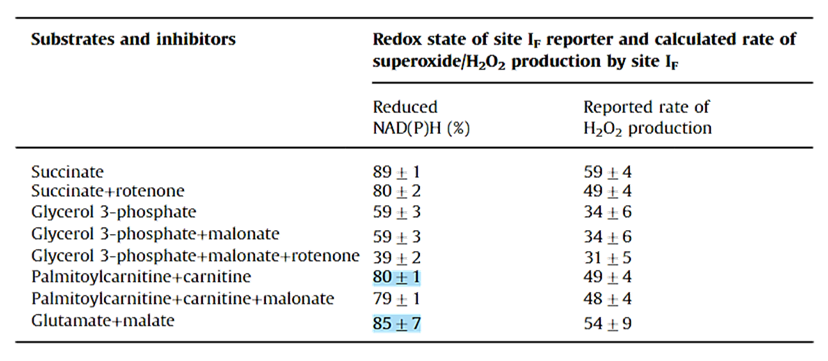

With this background, Martin and besties went through three phases in their research:

- Determining ROS-producing sites and their maximum capacities;

- Assessing native rates (from minimal inhibition) with select substrates; to later

- Evaluating a combination of substrates metabolized simultaneously.

ROS-producing capacities: Complex III, Complex I, SDH, and KGDHc stand out

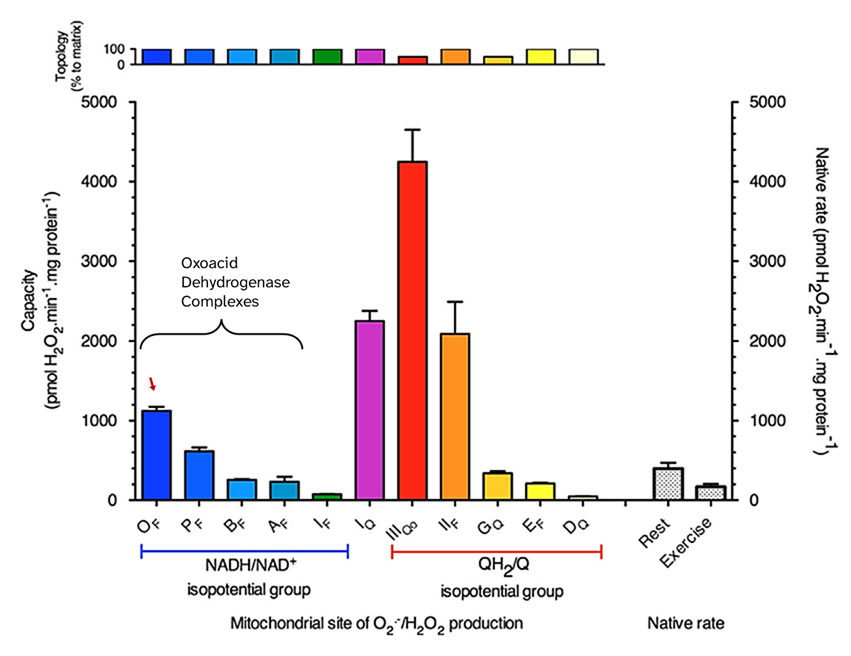

Starting with capacities, each bar below represents a ROS site that appeared as a red circle before, showing the capacity of those sites under maximizing conditions (with mitochondria isolated from rat skeletal muscle as model).

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M114.619072)

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001)'Topos' comes from Greek, meaning "I don't", while '-ology' means "care", so the 'topology' section on top shows that most mitochondrial enzymes release ROS entirely into the matrix. Complex III and GPDH are exceptions, with about 50% of their ROS being produced outward into the intermembrane space. Because many experiments use isolated mitochondria, superoxide that escapes unmetabolized can go undetected; in intact cells this superoxide would reach the cytosol, where it's more easily handled.

Bioenergetic quantum coaches (bio·qua·cs) fixate on Complex I, but the graphics so far already suggest that the picture is broader than that. For instance, SDH has a similar ROS-producing capacity and Complex III almost twice that of Complex I.

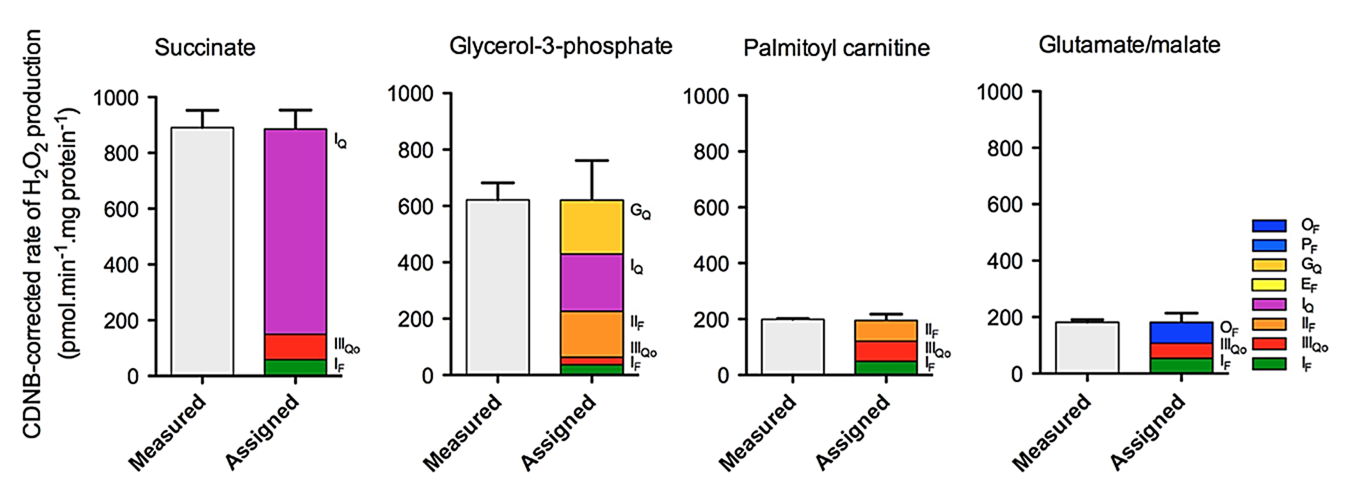

Approaching physiological conditions: 'native' ROS rates with select substrates

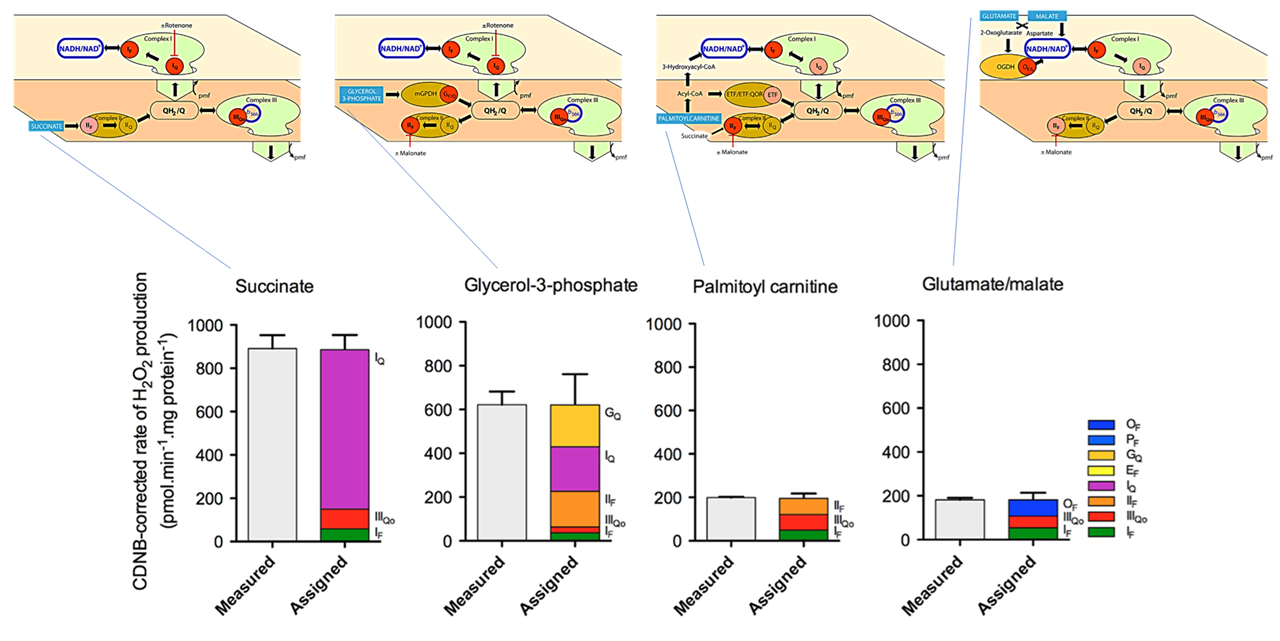

ROS capacities under maximizing conditions represent estimates of upper limits. Without artificial manipulations that overshoot ROS production, the effects of select substrates become less extreme:

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001)Concentrations used:

- 5 mM succinate

- 7 mM glycerol-3-phosphate

- 15 μM palmitoyl-carnitine

- 5 mM glutamate + 5 mM malate

Succinate is a TCA cycle metabolite that donates electrons directly into the respiratory chain. Even at 5 mM, succinate yields <1000 pmol H₂O₂/min/mg, which is far below what we would anticipate from capacities: >2000 pmol H₂O₂/min/mg.

Glycerol-3-phosphate derives primarily from glucose or from glycerol released during triacylglycerol breakdown, serving as an alternative electron donor to mitochondria. Its electrons enter the respiratory chain at a level comparable to that of succinate.

- Succinate → SDH → UQ ← GPDH ← Glycerol-3-phosphate

Their contrasting profile (refer to the figure) suggests that overloading the UQ pool with electrons yields varying responses depending on the source.

Palmitoyl-carnitine is palmitate bound to carnitine after conversion to the active form (palmitoyl-CoA), making it ready for mitochondrial import and oxidation. The effect of 5 mM plain succinate is much different from that of 15 μM palmitoyl-carnitine, a concentration within what cells may encounter.

Glutamate + malate favor electrons entry at Complex I. In the comparison above, it's the closest scenario to pyruvate + malate, with increased reliance on NAD-dependent respiration.

For context, we've shifted from ROS capacities measured under maximizing conditions to native rates with isolated substrates, without yet getting to semi-physiological mixtures. Because fatty acids are a frequent concern, undergo a more complex metabolism, and involve more sites with leakage potential, palmitate (as palmitoyl-carnitine) will serve as reference substrate for the discussions that follow.

-

ROS responses to palmitate oxidation

Back to the previous figure, but now with simplified routes shown on top and red circles marking the assigned sites:

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001)Based on the ROS contribution profile for palmitoyl-carnitine:

- Overall rate is relatively low

- Complex I is not the dominant source

- Forward electron transfer through Complex I (otherwise site Iq would also appear)

- Complex III and SDH are the main contributors

Complex III is often overlooked (not by researchers, but by bioenergetic quantum coaches) and SDH is even more ignored as a direct ROS source. When fatty acids are oxidized in mitochondria, additional potential contributors tend to be neglected as well: KGDHc, ETF, and ACADHs.

We'll first go through how metabolic inhibitors influence the overall ROS production from palmitoyl-carnitine, and then discuss each of the sources mentioned above individually.

Palmitoyl-carnitine: metabolic inhibitors, ROS responses, and some influencing factors

The earlier figure becomes useful again, showing where standard inhibitors act (red text):

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001)Site Standard inhibitor Iq ⊢ Rotenone IIf (Sf) ⊢ Malonate IIq (Sq) ⊢ Atpenin IIIqo ⊢ Myxothiazol/stigmatellin IIIqi ⊢ Antimycin Vo ⊢ Oligomycin kvothe.de None (unstoppable) (Palmitate → palmitoyl-CoA :: Malonate → malonyl-CoA)

These inhibitors disrupt electron flow, causing a redistribution that can confound interpretation. Martin and colleagues once more did a great job determining ROS contributors through deduction. However, they now favor molecules that prevent electron leakage at target sites without disrupting the flow (green text ⇈).

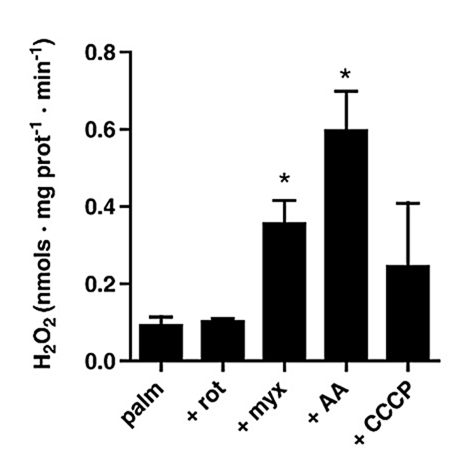

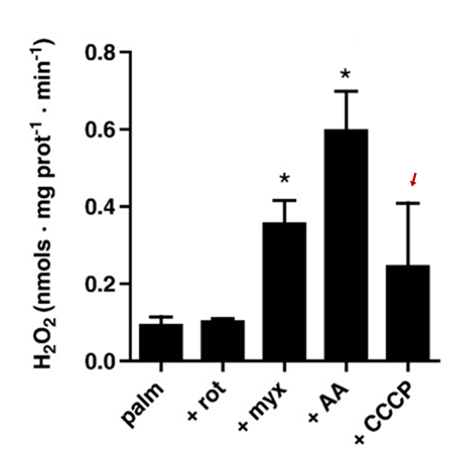

Nevertheless, standard inhibitors remain valuable and widely used. Their presence mirrors aspects of metabolic impairments and changes the overall ROS production rate from palmitoyl-carnitine:

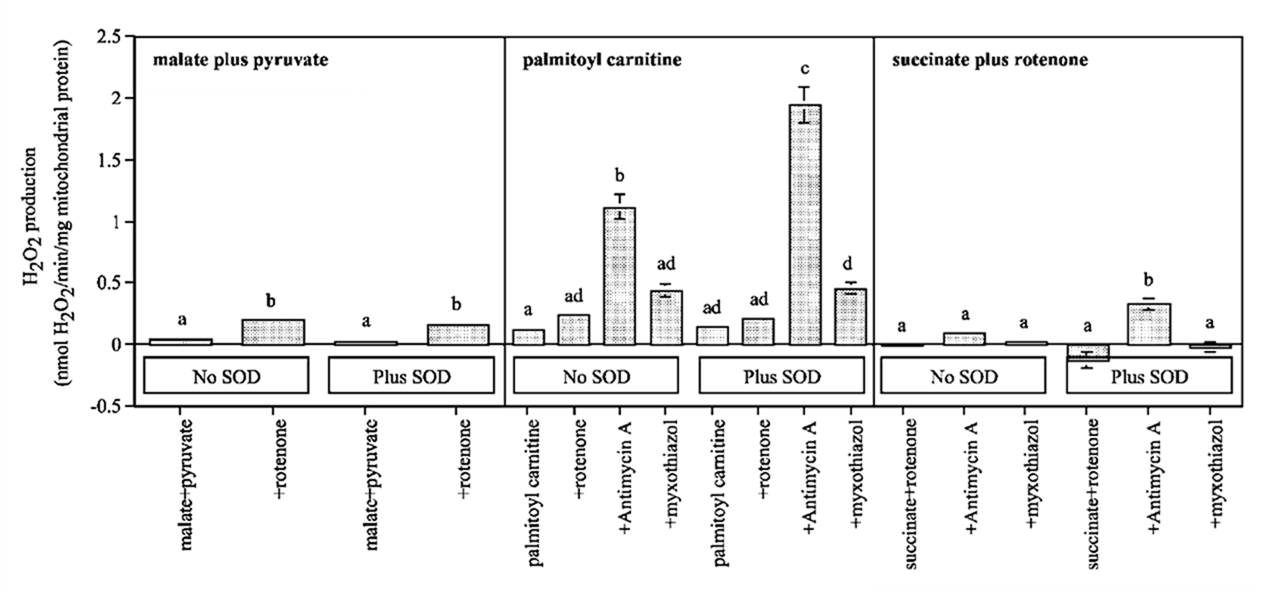

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.008)

⠀50 μM palmitoyl-carnitine⠀

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M109.026203)

⠀18 μM palmitoyl-carnitine⠀

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M207217200)

⠀60 μM palmitoyl-carnitine (+ 2 mM carnitine)⠀

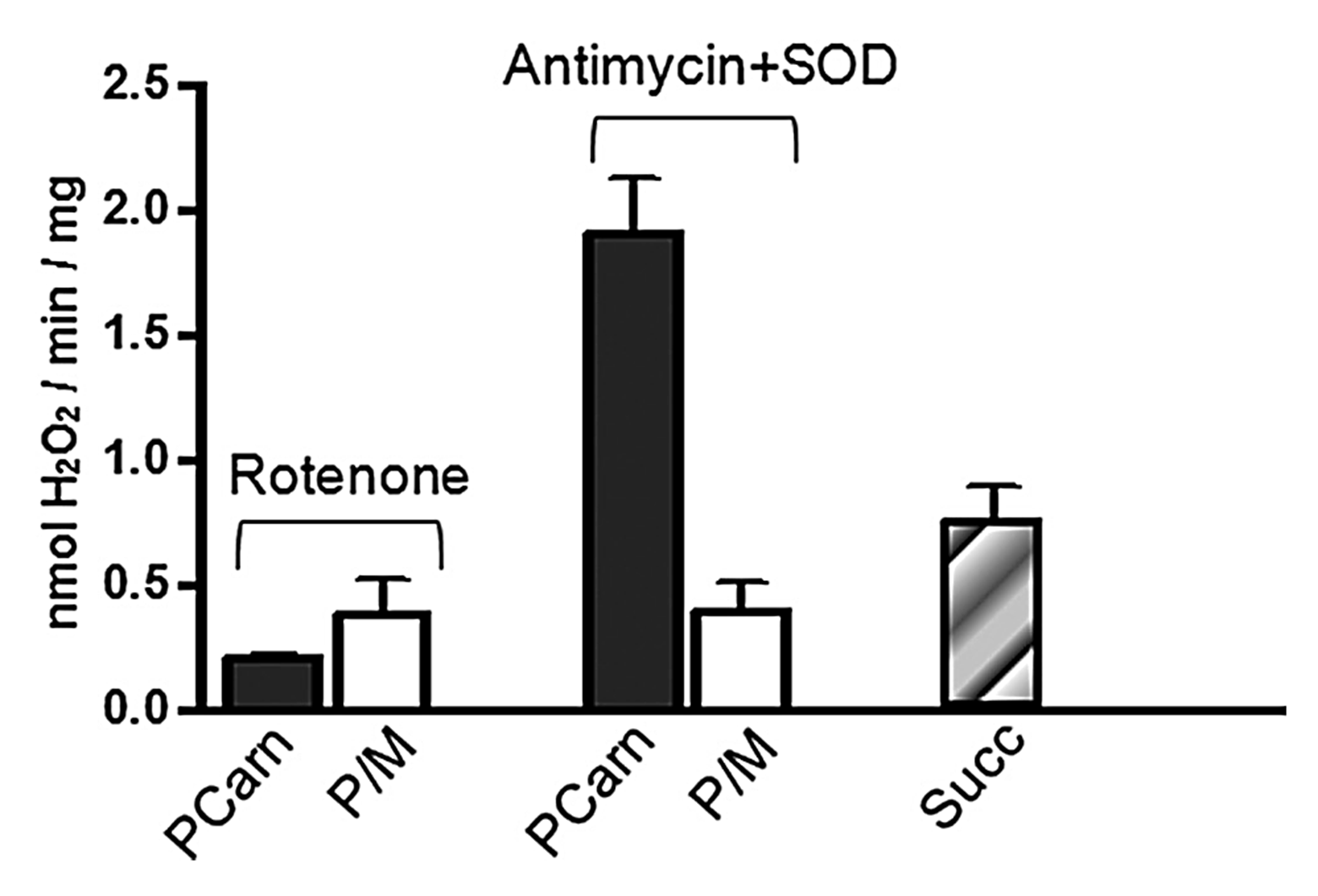

⠀(10.2337/db11-1437)

⠀40 μM palmitoyl-carnitine (+ 5 mM malate)These experiments used mitochondria isolated from rat muscle in resting state ("state 4") induced by oligomycin or minimal ADP, and were run under supraphysiological oxygen levels. In isolated mitochondria, added superoxide dismutase (SOD) compensates for losses of surface SOD, helping to detect part of superoxide released outward (~50% of that generated by Complex III, which may first pass through the lumen of cristae).

In the presence of antimycin, palmitoyl-carnitine generated far more ROS than succinate, especially surprising when rotenone (suppressor of succinate-derived ROS) was absent. Conversely, in the presence of rotenone, palmitoyl-carnitine produced ROS at similar or even lower rates than pyruvate + malate.

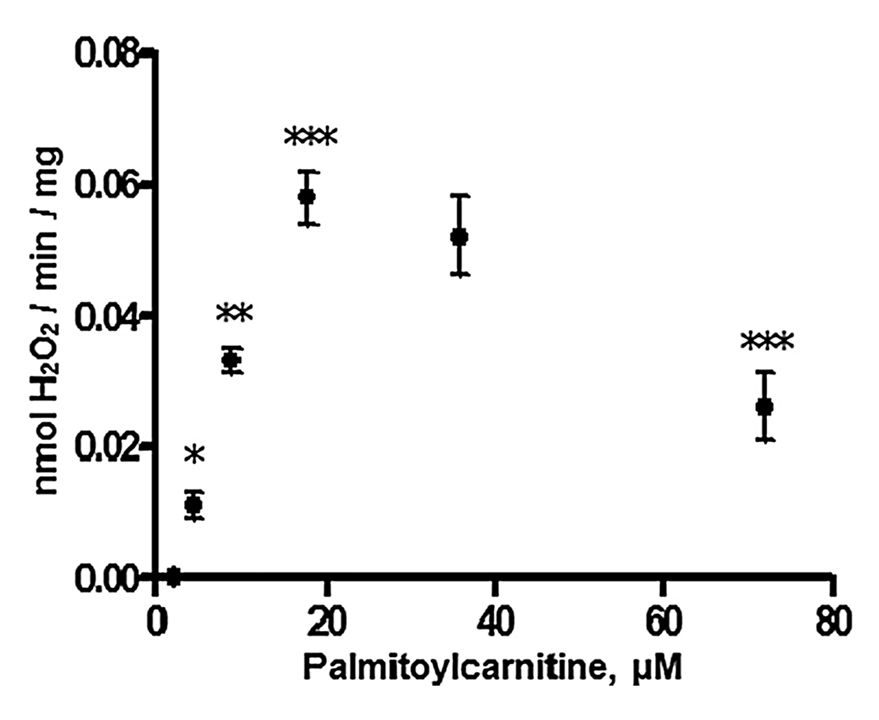

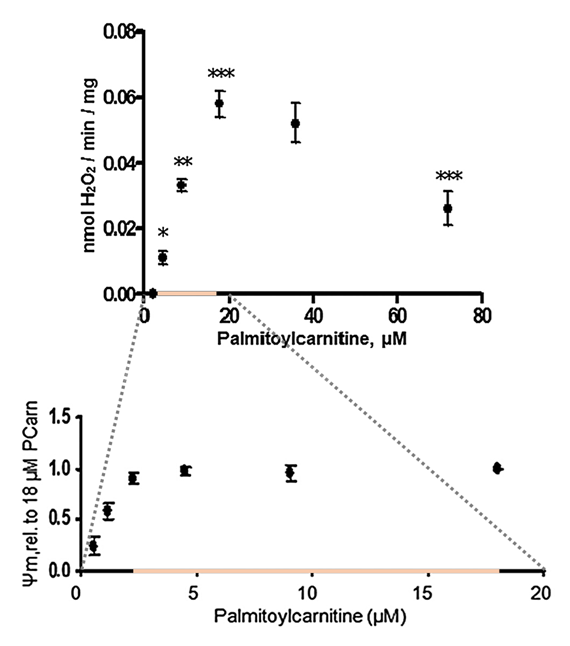

Concentration matters

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M109.026203)H₂O₂ production peaked at 60 pmol H₂O₂/min/mg with 18 μM palmitoyl-carnitine and lowered at higher concentrations, possibly because excess fatty acids can dissipate built-up protons (H⁺), promoting electron consumption and lowering ROS formation.

The dissipating effect can be direct (probable with free fatty acids rather than their esterified forms) or indirect (triggered by ROS and derivatives).

- Fatty acids as natural uncouplers preventing generation of O₂•⁻ and H₂O₂ by mitochondria in the resting state

- Induction of Endogenous Uncoupling Protein 3 Suppresses Mitochondrial Oxidant Emission during Fatty Acid-supported Respiration

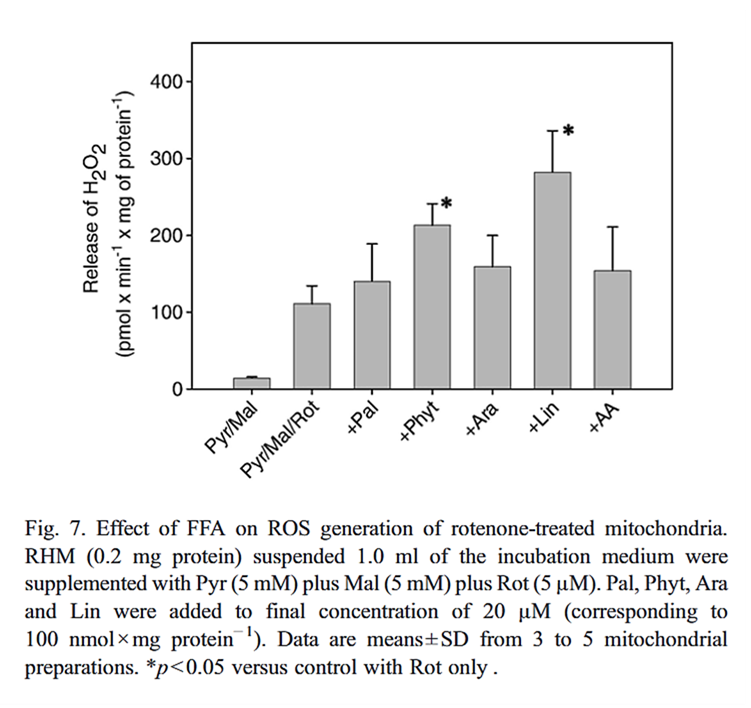

Fatty acid type matters

⠀(10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.04.005)Tissue specificity matters

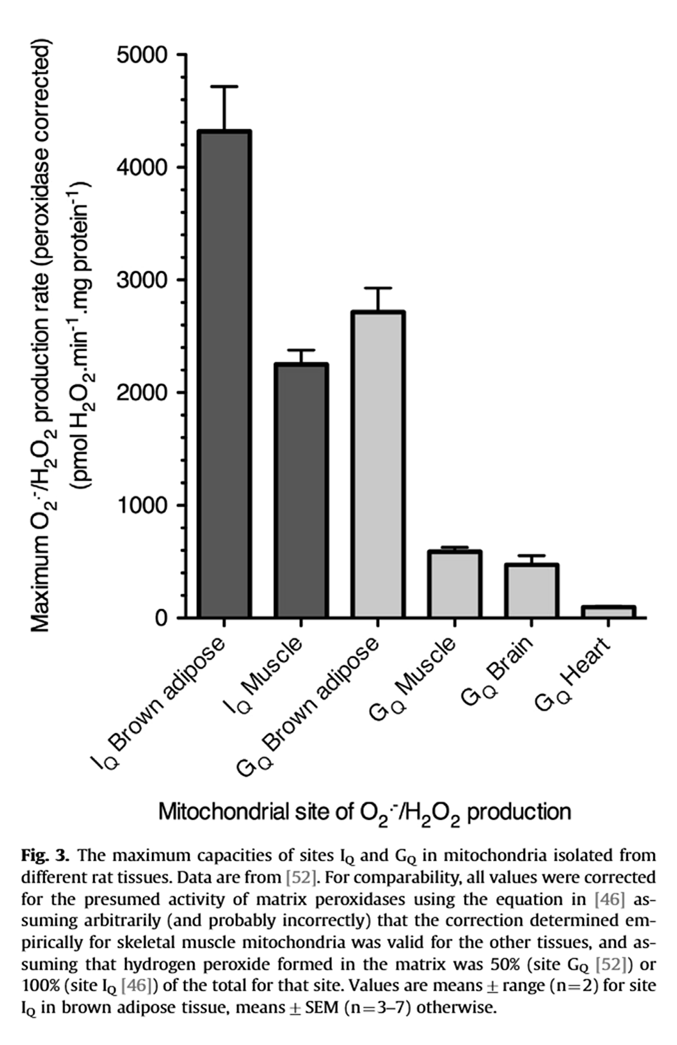

A site with relatively low ROS-producing capacity can occur more frequently in a tissue, increasing the contribution to the overall rate. For example, compare the production rate for Iq (higher capacity) in muscle with Gq (lower capacity) in brown adipose tissue.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001)Multiple factors result in different responses depending on the tissue:

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.008)Medium-chain fatty acids bypass the carnitine-dependent transport, so they enter mitochondria avoiding this regulatory step. But their metabolism concentrates in the liver, where excess acetyl-CoA from β-oxidation can convert into ketone bodies. Ketogenesis helps to export carbons, recover CoA, and (with further conversion of acetoacetate into hydroxybutyrate) reoxidize NAD, preventing local burden.

Ketogenesis therefore lifts oxidation constraints by regenerating CoA and eventually reoxidizing NAD. When ROS production is excessive, depletion of these cofactors can limit electron supply and curb further ROS generation.

Mitochondrial state matters

A shift from a resting to stimulated state ("state 4" → "state 3") increases electron demand relative to supply, decreasing their availability at susceptible sites, and minimizing leakage.

- Individuals with higher metabolic rates have lower levels of reactive oxygen species in vivo

- Decreased mitochondrial metabolic requirements in fasting animals carry an oxidative cost

- Cellular oxidative damage is more sensitive to biosynthetic rate than to metabolic rate: A test of the theoretical model on hornworms (Manduca sexta larvae)

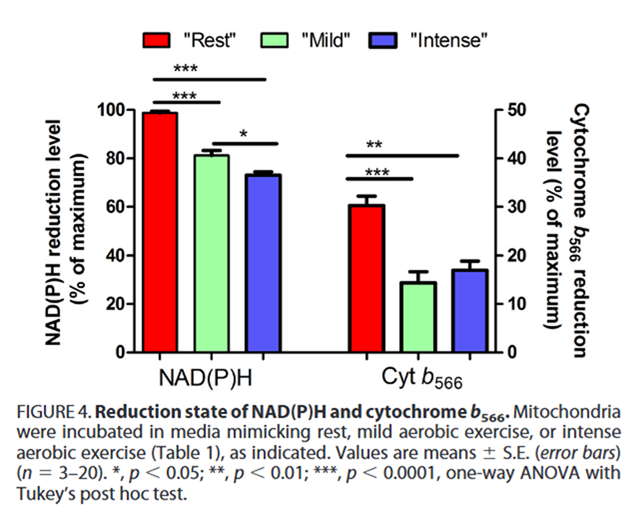

Exercise-mimicking conditions decrease ROS production from cellular respiration:

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M114.619072)But that also calls for alternative explanations for the exercise-induced ROS increase.

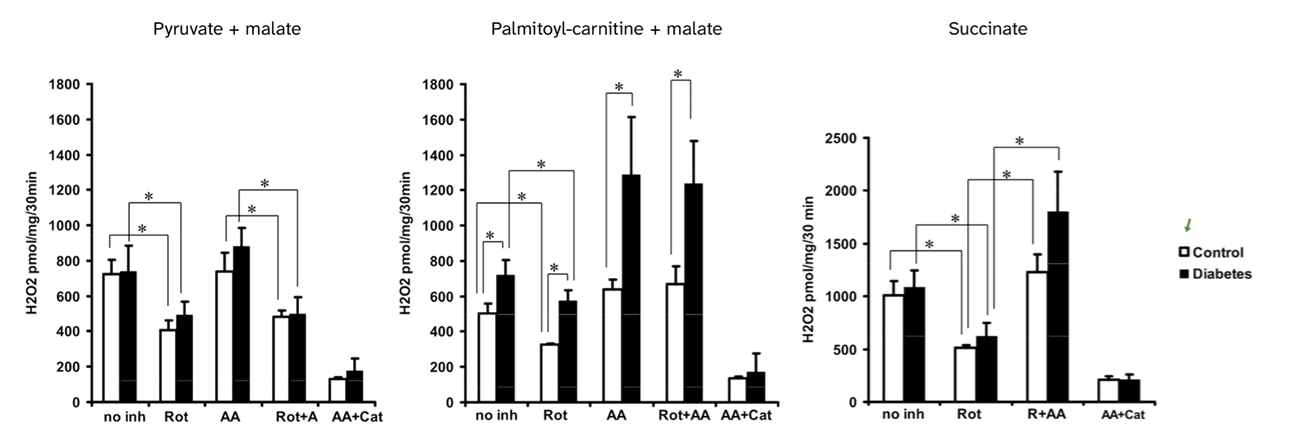

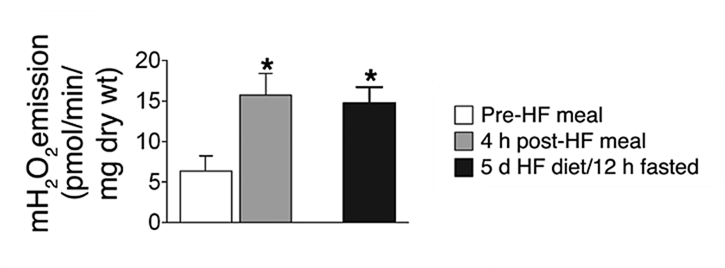

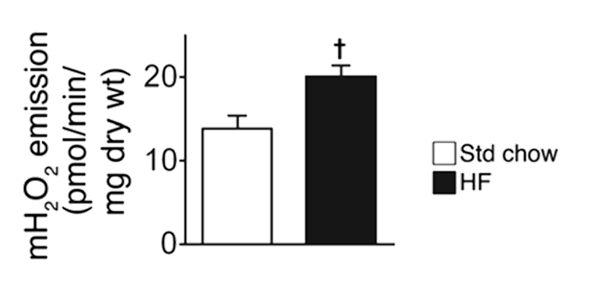

Pre-condition matters

The following experiments relied on:

- Permeabilized muscle strips

- High-fat intervention diets (~60% fat) for pre-conditioning

- 25 μM palmitoyl-carnitine + 2 mM malate as the challenge

A single high-fat meal markedly changes the response of muscle strips from lean individuals to palmitoyl-carnitine + malate. The same effect is noticed after 5 days on a high-fat diet followed by a 12-hour fast before the challenge.

⠀(10.1172/JCI37048)After 6 weeks on a high-fat diet, rat muscle strips still show an unexpected response to a substrate that they should have adjusted to, suggesting that lipid overload prevents proper adaptation.

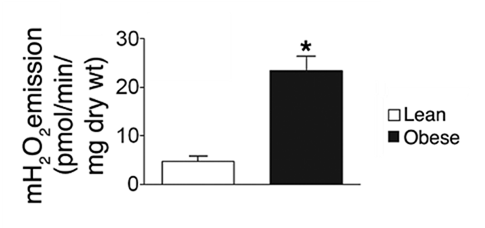

⠀(10.1172/JCI37048)Muscle strips from lean versus obese individuals also respond much differently to the same challenge:

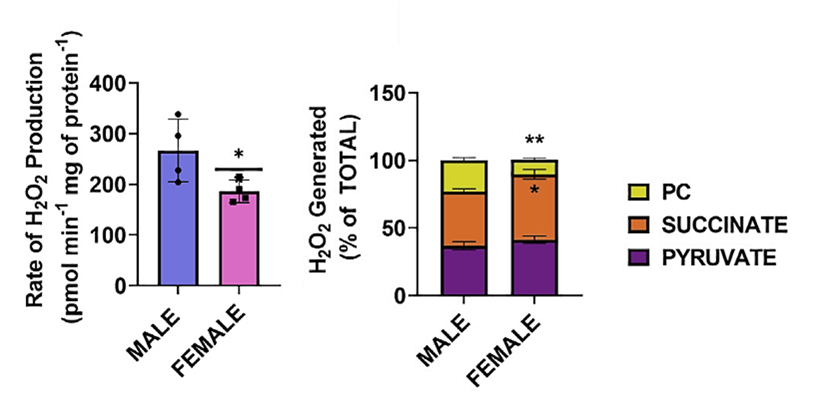

⠀(10.1172/JCI37048)Sex matters

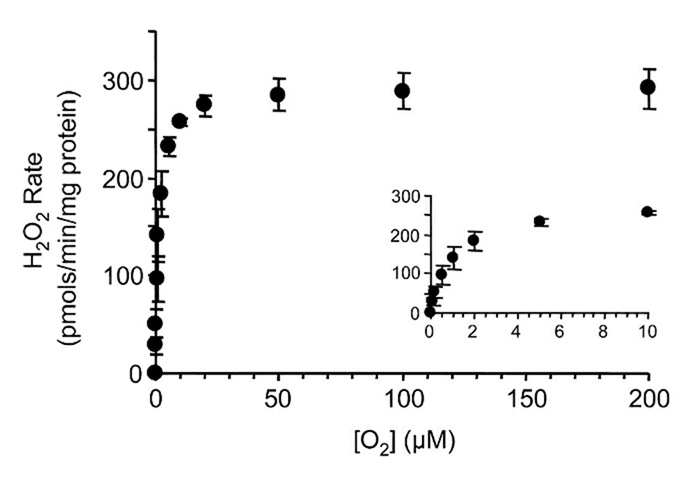

⠀(10.1016/j.jbc.2024.107159)Oxygen availability also matters

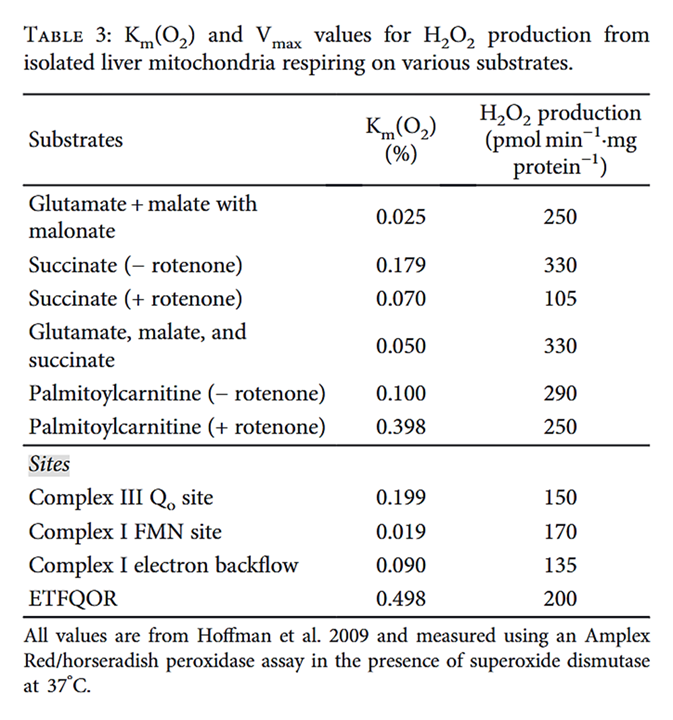

Since respiratory complexes function at O₂ levels that already exceed their saturation, supraphysiological O₂ levels in experiments have little effect on ROS production.

However, ROS generation decreases as O₂ levels become critically low, and enzymes differ in O₂ affinity, giving them varying sensitivities to hypoxia.

Palmitoyl-carnitine at a low concentration:

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M809512200)

⠀(10.1155/2018/8238459)In the absence of O₂, enzymes can't produce ROS because the substrate is missing.

- Hypoxia decreases mitochondrial ROS production in cells

- Oxygen Sensitivity of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Generation Depends on Metabolic Conditions

- How Supraphysiological Oxygen Levels in Standard Cell Culture Affect Oxygen-Consuming Reactions

Fatty acid oxidation demands more O₂ than glucose oxidation to compensate for metabolic inefficiencies. This need is easily met by modest increases in delivery, but may deplete O₂ further when delivery is impaired.

Uncouplers of oxidative phosphorylation control ROS production

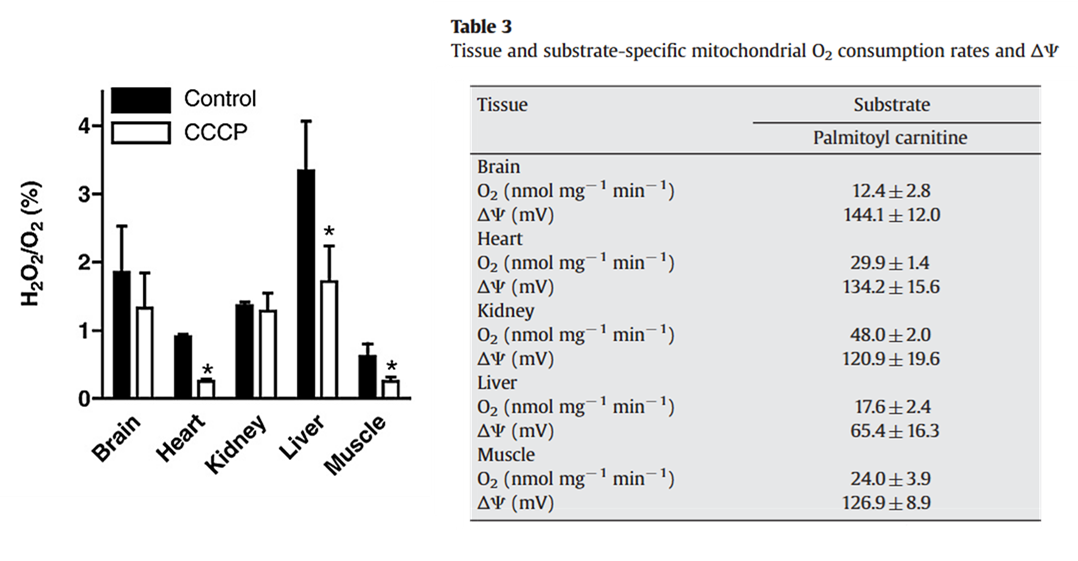

The limited efficacy of CCCP ("mitochondrial uncoupler") in normalizing ROS production deserves a few comments.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.008)The primary purpose of respiration is ATP synthesis. Protons concentrated by respiration dissipate back into mitochondrial matrix through Complex V (ATP synthase), but some return via alternative dissipation pathways as well. Mitochondrial uncouplers increase the relative contribution of those alternative pathways, making oxidation less tied to phosphorylation, allowing oxidation to continue without being limited by the need for ATP.

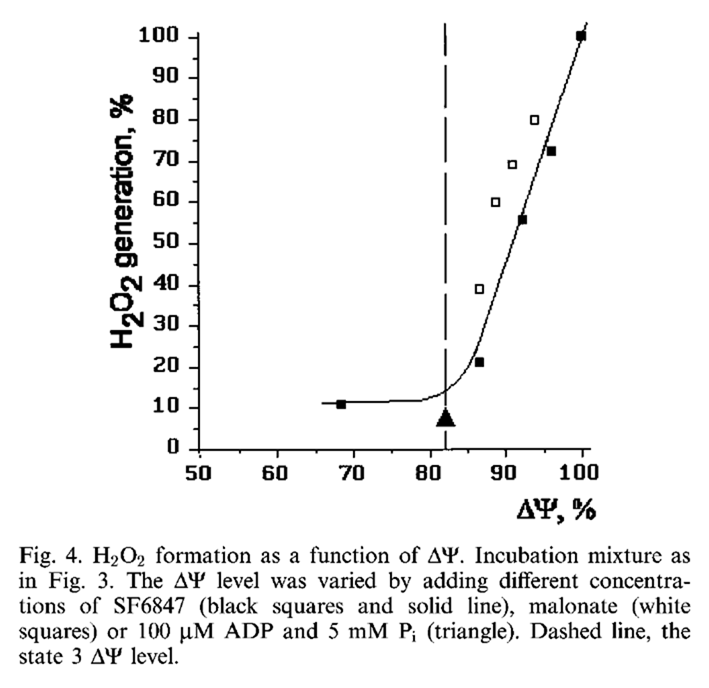

Uncouplers (acting as dissipators) increase the rate of electron consumption to compensate for the energetic inefficiency. Before the electron supply catches up, the respiratory chain becomes more oxidized, decreasing the electron availability at susceptible sites, preventing leakage, and lowering ROS. Uncouplers counteract the tendency for ROS to rise as the 'membrane potential' ("Δψ") increases:

⠀(10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01159-9)However, with palmitoyl-carnitine, ROS production continues to increase when the potential is already maximized.

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M109.026203)- Maximal ψₘ occurs at ≥2.5 μM palmitoyl-carnitine;

- Maximal H₂O₂ occurs at 18 μM palmitoyl-carnitine.

Keeping 18 μM palmitoyl-carnitine constant and lowering the membrane potential with FCCP (another mitochondrial uncoupler; black bars) produces the expected moderate suppression:

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M109.026203)The decrease reflects the ROS fraction that depends on membrane potential. Uncoupling suppressed ROS from glutamate + malate (NAD-oriented substrates) far more effectively than from palmitoyl-carnitine. This suggests that a substantial portion of ROS generated with palmitoyl-carnitine is independent of the state of the respiratory chain, so uncouplers can't affect that portion (the remaining 55%).

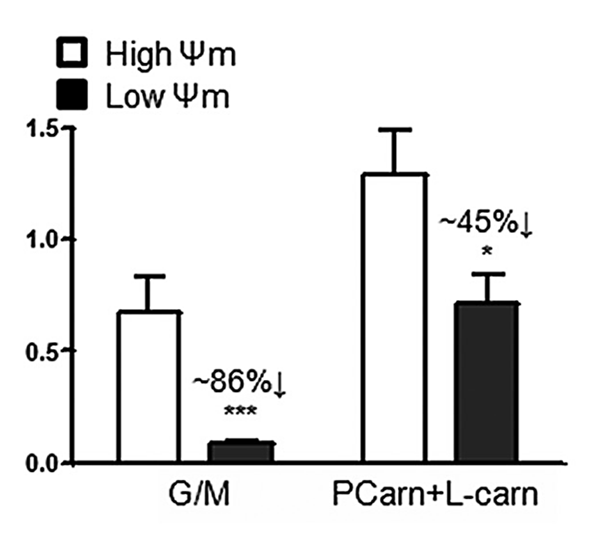

Interestingly, stimulating the respiratory chain drains more electrons from the UQ pool than from the NAD pool.

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M114.619072)Cyt b566 (also called cyt bL) is one of the redox centers of Complex III that interacts and equilibrates with UQ, serving as a proxy for the local UQ redox state.

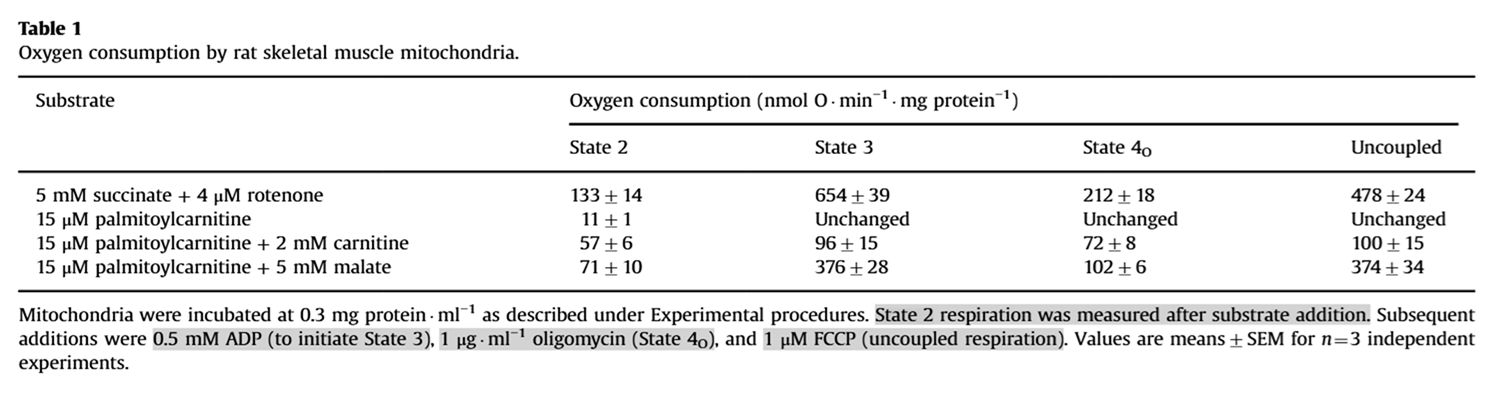

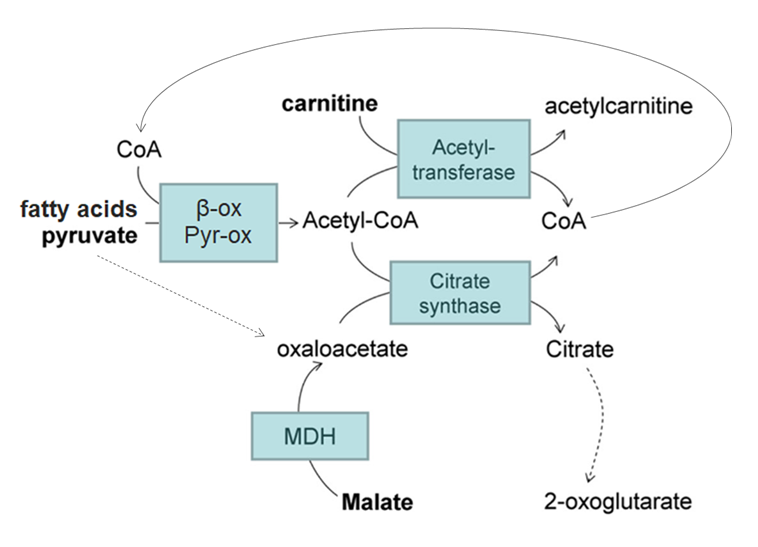

Supplementary carnitine and malate disinhibit fatty acid oxidation

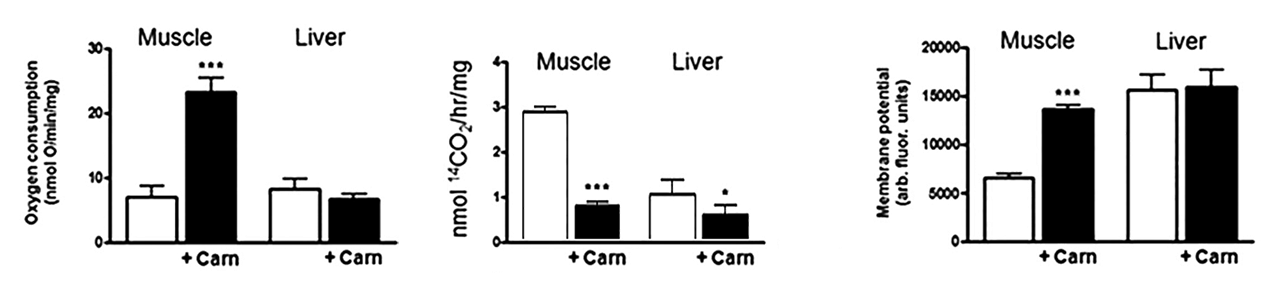

Regarding the addition of free carnitine (+ L-carn) in one of the graphs, it's common in experiments to combine palmitoyl-carnitine with extra carnitine or malate because sustaining high rates of plain palmitoyl-carnitine oxidation is difficult, as reflected in low rates of oxygen consumption regardless of interventions (such as added ADP) that would normally change the rate:

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.006)Additional carnitine or malate (an importable oxaloacetate precursor) overcomes that limitation.

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M113.545301)When acetyl-CoA production exceeds oxaloacetate regeneration, acetyl-CoA accumulates and sequesters CoA, impairing β-oxidation but also other CoA-dependent processes (PDHc, KGDHc, etc.).

β-oxidation impairment (as from insufficient CoA) can result in accumulation of intermediate metabolites. Compared with malate/oxaloacetate, carnitine has the advantage of exporting these incomplete β-oxidation intermediates, preventing their buildup, that would otherwise risk further perturbations and more ROS.

Unlike fatty acids, pyruvate can divert from acetyl-CoA into oxaloacetate (dashed line), restoring the acetyl-oxaloacetate balance and freeing CoA; excess acetyl groups can then be exported as citrate if needed.

As an interesting side note, it's possible with fatty acids to sustain respiration with minimal decarboxylation (↝CO₂). That's because β-oxidation (first stage) channels electrons into the respiratory chain (via ETF and NAD) independently of the TCA cycle (second stage, where decarboxylation occurs).

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M109.026203)Altogether, those reasons explain the three compositions tested for each scenario ahead:

- Palmitoyl-carnitine alone

- Palmitoyl-carnitine + extra carnitine

- Palmitoyl-carnitine + malate

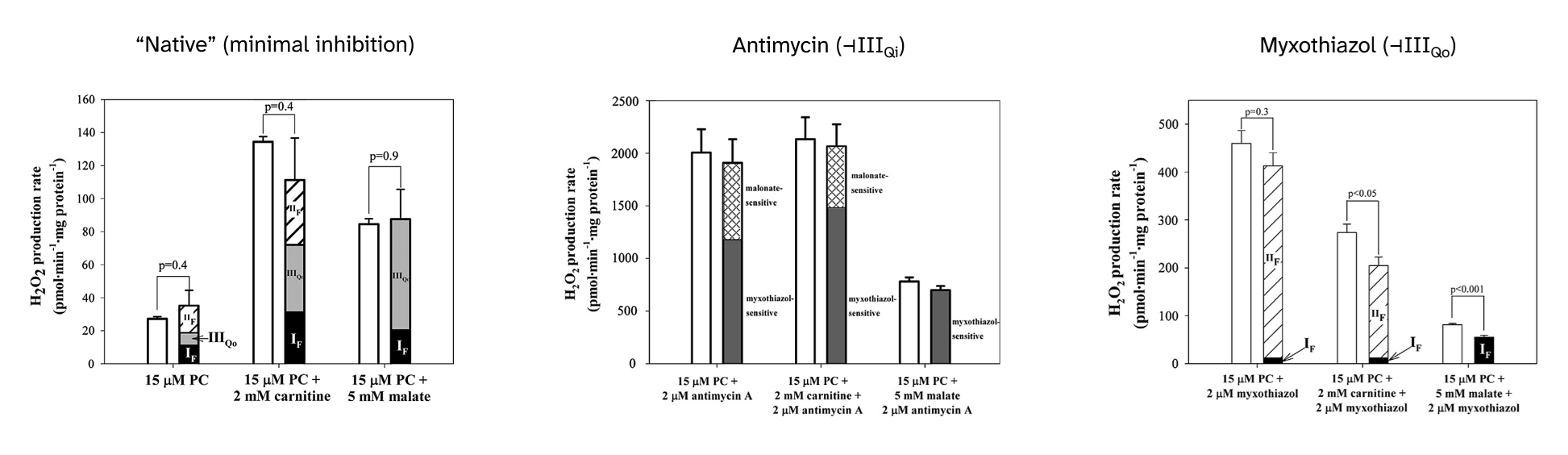

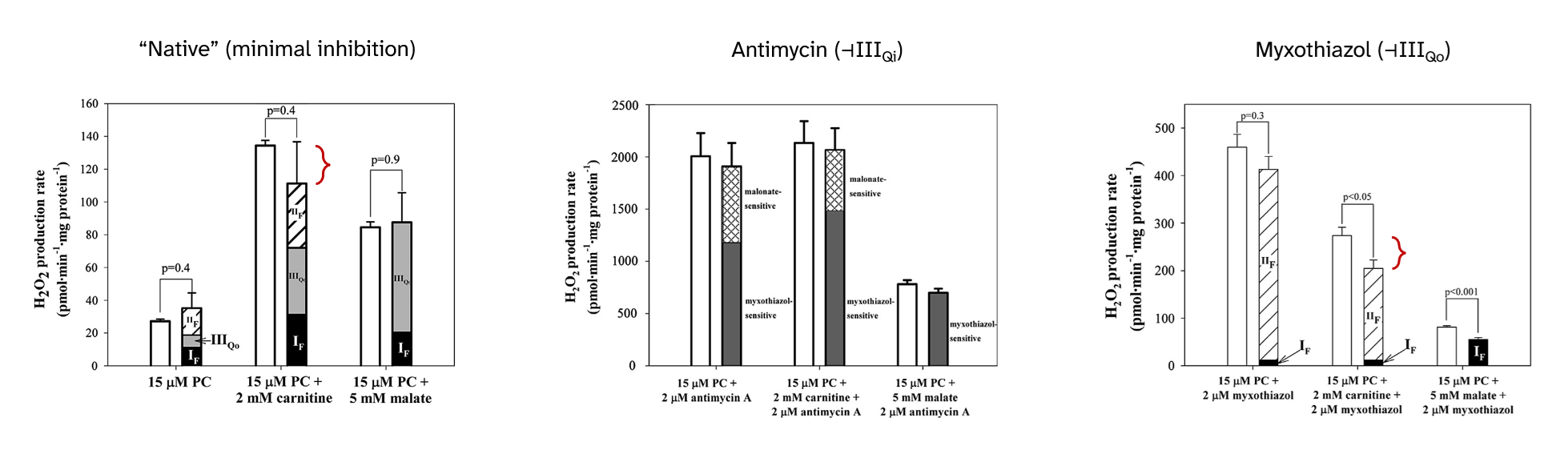

Palmitoyl-carnitine: ROS contribution profiles and their response to inhibitors

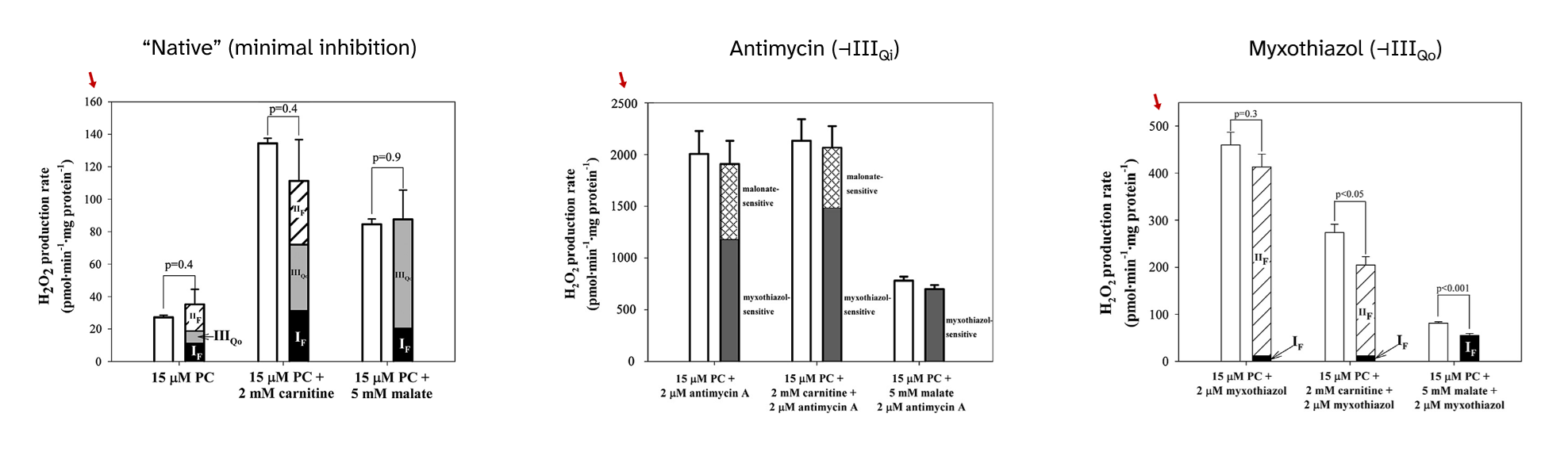

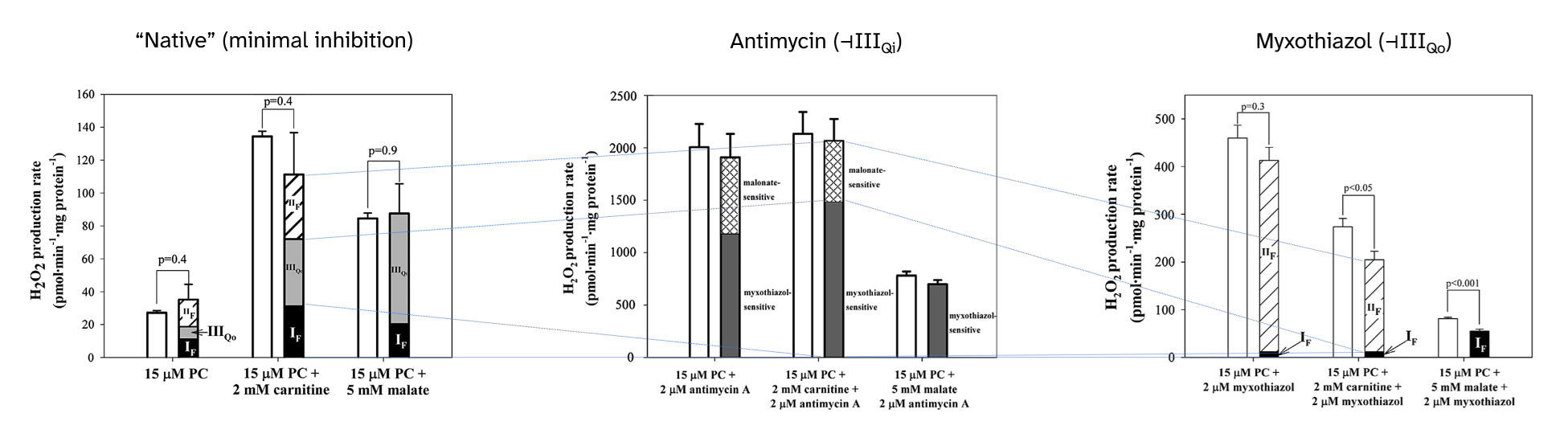

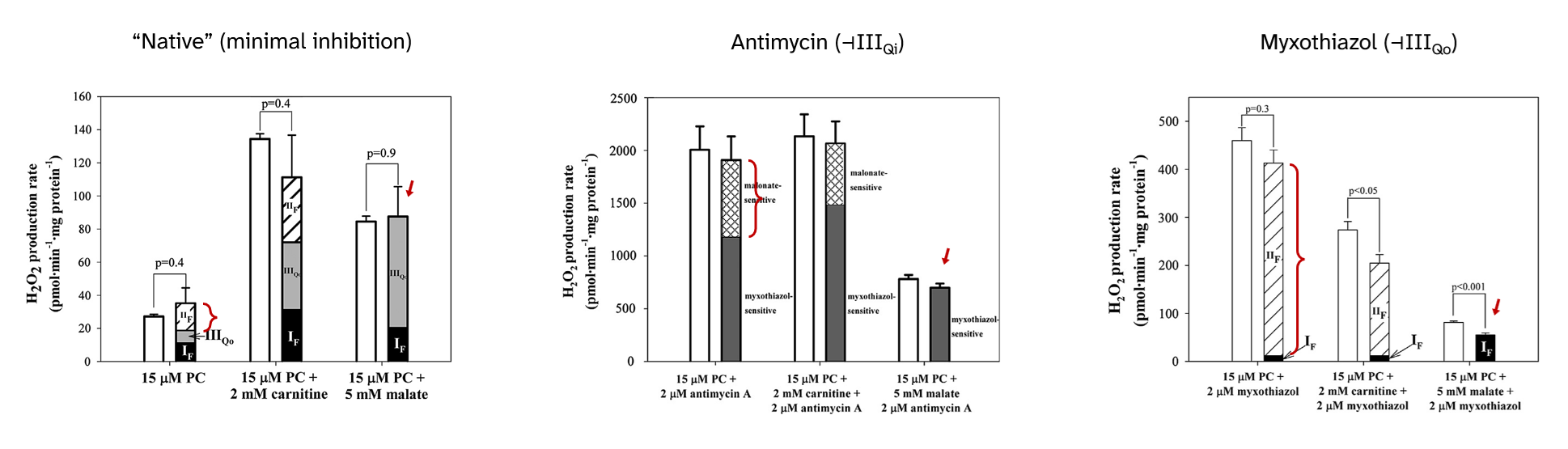

Returning to inhibitors, their presence not only affects the overall ROS production rate, but also changes the contribution profile:

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.006)

⠀15 μM palmitoyl-carnitine (+ 2 mM carnitine or + 5 mM malate)[Still using mitochondria isolated from rat muscle in resting state ("state 4") induced by oligomycin or minimal ADP, under supraphysiological oxygen levels.]

With palmitoyl-carnitine + carnitine as reference, we had:

Scenario Detected H₂O₂ (pmol/min/mg) Contributors "Native" (uninhibited) ~140 ▸IIIqo + ▸IIf + ▸If + ▸Kf? + ▸Ef? Antimycin (⊣IIIqi) ~2150 ▸IIIqo + IIf◃ Myxothiazol (⊣IIIqo) ~250 IIf◃ + ▸If + ▸Ef? ▸ Forward electron flow

◃ Reverse electron flowThe following sections will address each of the overlooked ROS contributors with the depth of a conversation with drunk Spring Break Britney.

To put them in context:

-

Complex III and its hospitalizing ROS-producing site

- Antimycin poorly recreates a condition of excess UQH₂ with exaggerated electron supply;

- Myxothiazol poorly recreates a condition of UQH₂ accumulation from insufficient demand, as if Complex IV was inhibited.

Both inhibitors act on different sites of Complex III, compromise UQ oxidation, yet minimize the relative contribution of Complex I.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.006)Antimycin leaves the site with the highest ROS-producing capacity (IIIqo) available shortly before the level of inhibition (IIIqi). As a result, electrons accumulate on an arm of Complex III responsible for completing UQH₂ oxidation, favoring the occurrence of a quinone radical with access to oxygen, driving ROS overproduction.

In contrast to antimycin, myxothiazol targets the hospitalizing site (IIIqo), rendering it unavailable and eliminating the contribution of Complex III, leaving that of SDH (Complex II) to prevail. In this situation, a significant fraction remains unassigned, which the authors suppose to come from ETF, and will be addressed later.

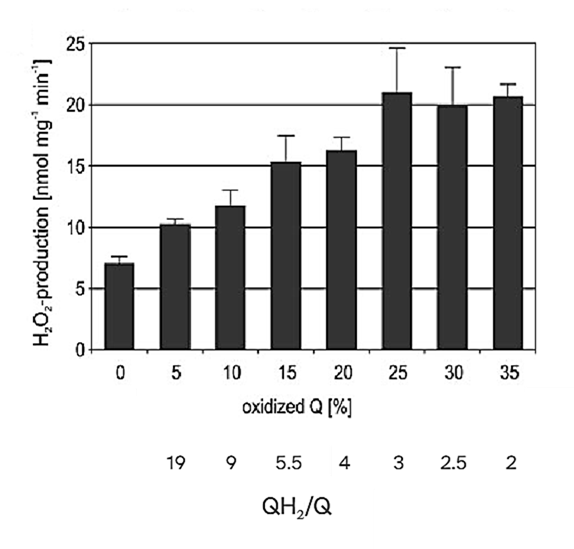

Extreme electron accumulation in the UQ pool can suppress ROS production, so the peak occurs when the UQ pool is still partially oxidized:

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M803236200)That suppressive effect might not have applied in the guiding experiment because electrons could escape to available complexes, preventing saturation of the UQ pool.

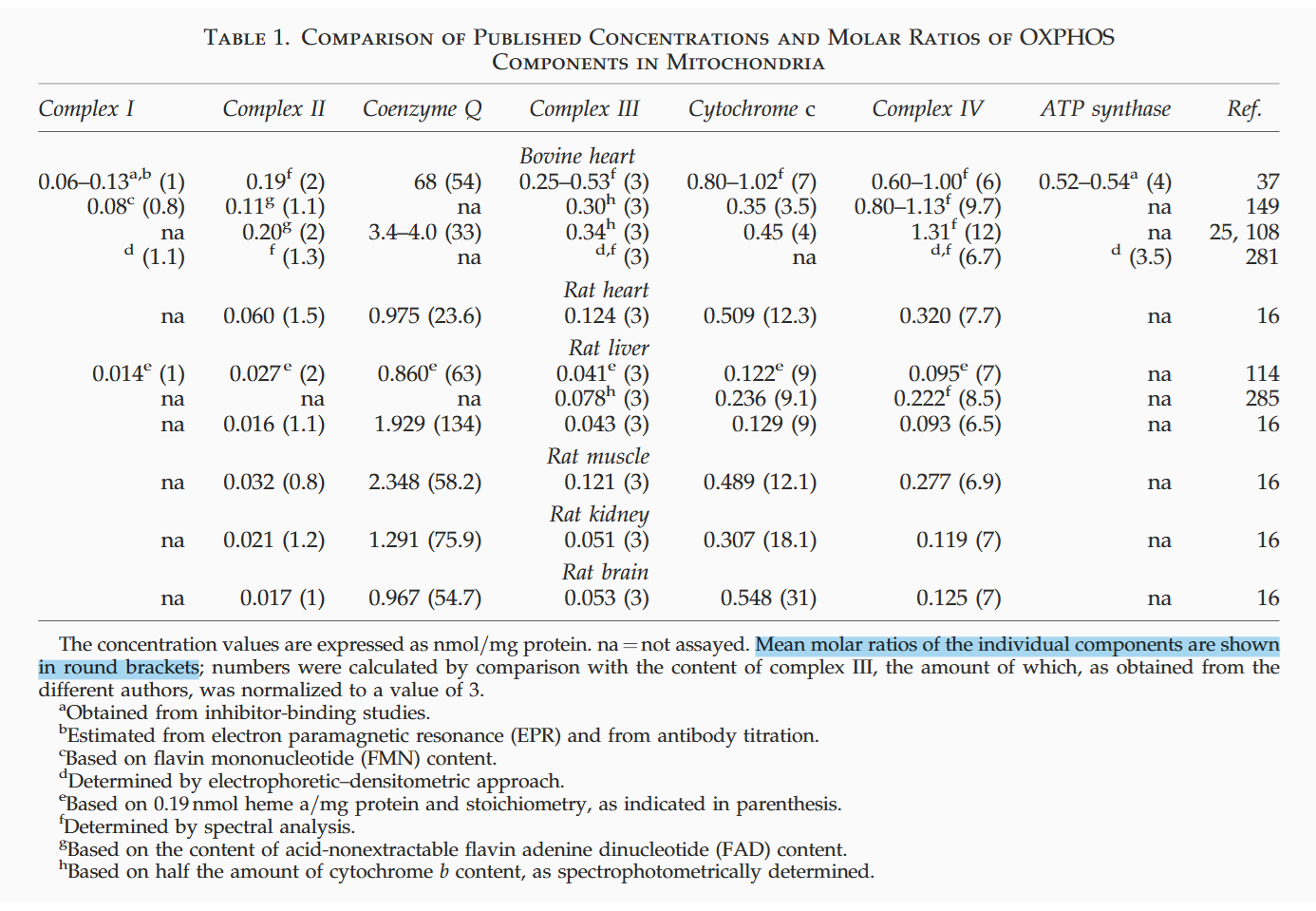

UQ is present in excess relative to other respiratory components:

⠀(10.1089/ars.2009.2704)Even after discounting a non-mobilizable fraction, UQ remains in excess:

Muscle Liver Complex II 0.8 1 - Ubiquinone 61 131 Complex III 3 3 - Cytochrome c 12 9 Complex IV 6.8 6.5 ⠀

Muscle Liver Ubiquinone (UQ) ↳ Utilized 13% 56% ↳ Mobilizable 8% 23% ↳ Non-mobilizable 79% 21% Cytochrome c (Cyt c) ↳ Utilized 63% 43% ↳ Mobilizable 17% 40% ↳ Non-mobilizable 20% 17% A shift in substrate oxidation can therefore perturb UQ-linked complexes and increase ROS production without full saturation of the UQ pool. Impaired UQ synthesis in disease predisposes the pool to saturation, but many escape routes remain available for electrons to spill over.

Yet, electrons from UQ can be productively handed off, turning UQ into an antioxidant that helps to neutralize ROS.

- The antioxidant role of coenzyme Q

- Antioxidant effects of ubiquinones in microsomes and mitochondria are mediated by tocopherol recycling

- Electron Transport-Linked Ubiquinone-Dependent Recycling of a-Tocopherol Inhibits Autooxidation of Mitochondrial Membranes

Although the behavior of Complex III (and downstream processes) determines the rate of electron clearance from the UQ pool, this factor is rarely taken into account; concerns usually stop broadly at the oxygen consumption rate, if at all.

An important detail: when Complex III is inhibited (by antimycin or myxothiazol) and UQH₂ accumulates, the large ROS contribution from SDH (Complex II) no longer occurs under its forward operation as in the uninhibited condition, but from SDH operating in reverse (labeled 'IIf◃' in the top, "scenario" table).

SDH (Complex II) as an overlooked ROS source in forward and reverse electron flow

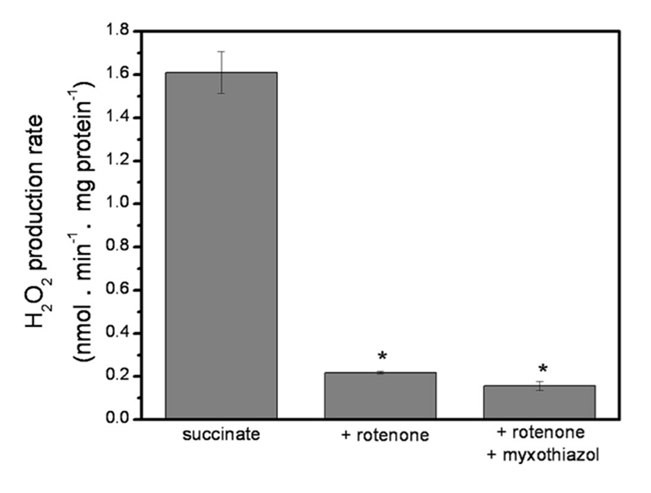

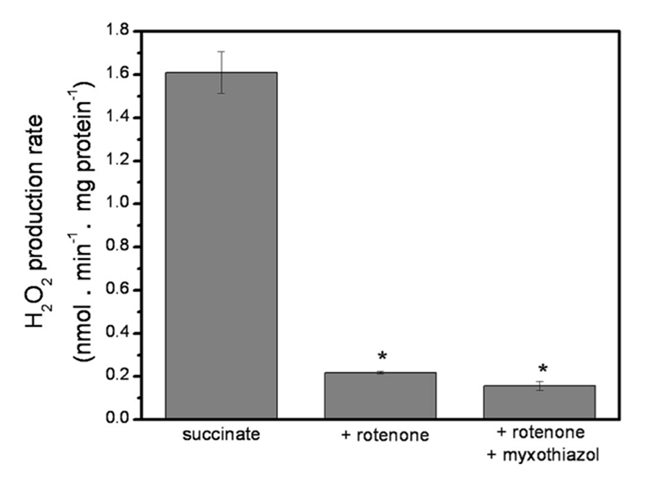

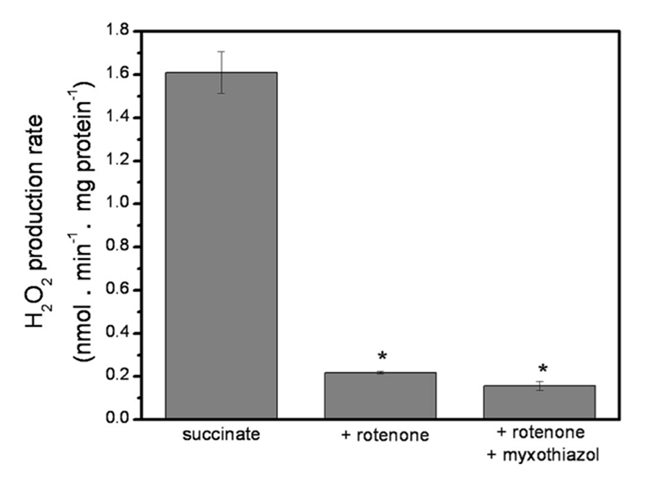

Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) can readily metabolize high succinate concentrations and overproduce ROS, known to originate mainly from Complex I (site Iq), as shown previously.

Rotenone (⊣Iq) suppresses most ROS generated from excess succinate oxidation (figure below), revealing classic Reverse Electron Transfer

. Inhibiting site Iq not only eliminates its own ROS contribution, but also prevents extensive electron backflow, leakage at site If, and NAD pool overload. This 'succinate-driven reduction of NAD' was already reported in early research, and may also affect oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes.

. Inhibiting site Iq not only eliminates its own ROS contribution, but also prevents extensive electron backflow, leakage at site If, and NAD pool overload. This 'succinate-driven reduction of NAD' was already reported in early research, and may also affect oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes.Combining rotenone with myxothiazol (⊣IIIqo) decreases the production rate further.

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M112.374629)

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M112.374629)Because Complex I, SDH, ETFDH, GPDH, Complex III, and other respiratory complexes converge on the UQ pool, inhibiting Complex I (Iq) and Complex III (IIIqo) reroutes electrons to available complexes sharing this pool, which complicates interpretation. Also, malate derived from succinate becomes an additional confounder.

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M112.374629)Recall that Complex I can generate ROS from its flavin (low-capacity) and quinone (high-capacity) sites, and that electrons can be sourced from NADH (forward mode) or UQH₂ (reverse mode).

Uninhibited Complex I could therefore receive electrons originating from succinate through either donor on opposite ends (NADH ← malate ← succinate → UQH₂). To rule out NADH as a substantial donor, consider the reactions:

Metabolites Enzyme Metabolites ↳ NADH + UQ + 2H⁺ ←{Complex I}→ NAD⁺ + H⁺ + UQH₂ ↰ → Succinate + UQ ←{SDH}→ Fumarate + UQH₂ ⬐ Malate ←{FH}→ Fumarate ↲ Malate + NAD⁺ ←{MDH}→ Oxaloacetate + NADH ↴ + H⁺ Succinate is oxidized to fumarate, then to malate*, and finally to oxaloacetate. Without an acetyl-CoA source (as is the case with plain succinate), oxaloacetate accumulates, product-inhibiting malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and limiting NADH generation.

- *Malate can be converted to pyruvate via ME, but this fate is less common than its conversion to oxaloacetate.

Moreover, Complex I operating in reverse can produce NADH in large amounts, with electrons coming from UQH₂ (first row of the table). Excess NADH, along with accumulated oxaloacetate, further inhibits MDH oxidation. These factors combined exclude malate as a substantial electron donor when succinate is the sole substrate.

The inhibitory effect of excess oxaloacetate extends beyond MDH to also suppress SDH oxidation.

- Malate ⇄ Oxaloacetate ⊣ SDH

In the guiding experiment, extra malate (an oxaloacetate precursor) eliminated the ROS contribution from SDH, suggesting that SDH was inhibited:

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.006)All succinate derivatives can act as SDH inhibitors:

- Succinate ←{SDH}→ Fumarate ⇄ Malate ⇄ Oxaloacetate

Oddly, even succinate might

product-substrate-inhibit SDH, but this should be irrelevant under normal conditions, in which oxaloacetate is the most potent and relevant inhibitor.Release of fatty acids (yielding acetate as acetyl-CoA) can coincide with release of glycerol (yielding oxaloacetate) or amino acids (also yielding oxaloacetate via glutamate), so their metabolism complement each other to avoid an inhibitory acetate-oxaloacetate imbalance.

Having ruled out malate as substantial electron source in exclusive succinate oxidation leaves us with respiratory complexes connected through UQ to consider.

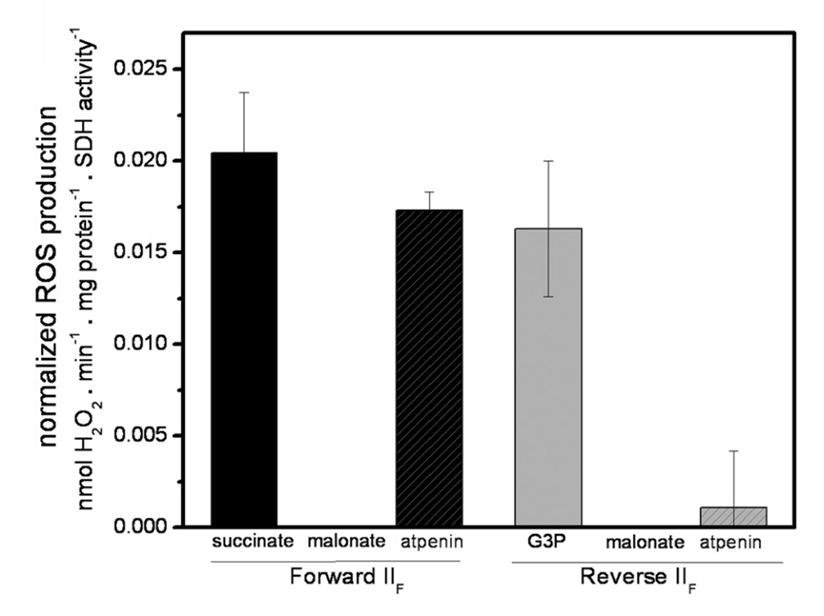

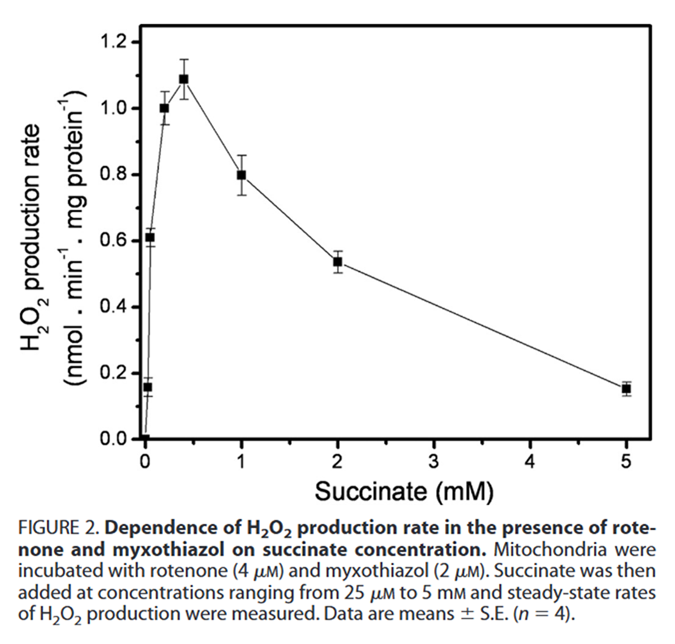

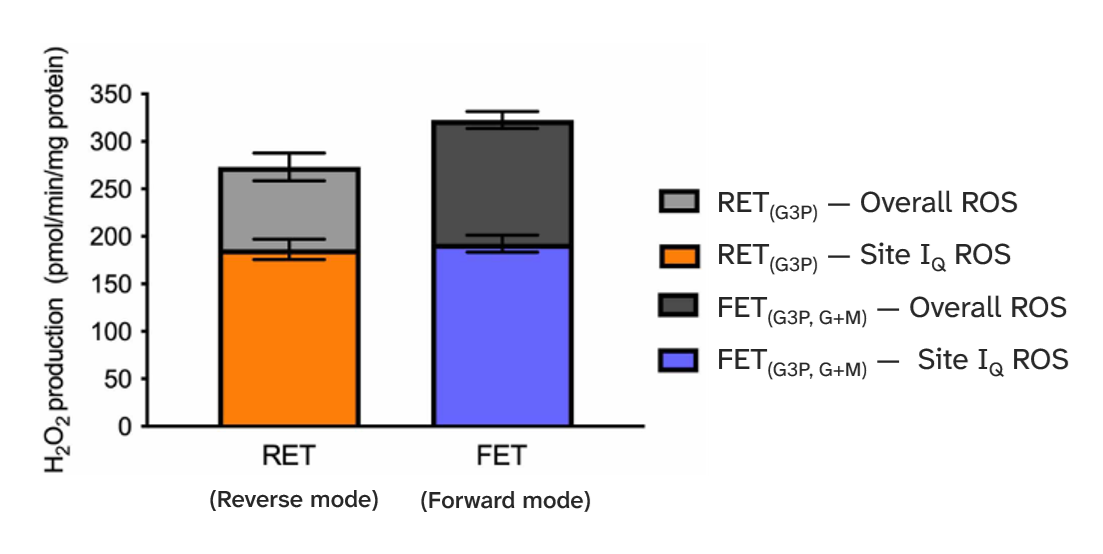

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M112.374629)The remaining ROS signal in the presence of rotenone (⊣Iq) and myxothiazol (⊣IIIqo) actually comes from SDH itself, as malonate abolishes the emission whether SDH operates in forward or reverse mode. ROS arises specifically from its flavin site. To arrive on this conclusion, the authors relied on the following manipulations.

Electron donors:

- Succinate → forward SDH operation

- Ubiquinol → reverse SDH operation

- Ubiquinol can in turn receive electrons from many donors. In this experiment, glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P; a derivative of glucose, glycerol, etc.) was used to overload the UQ pool and drive reverse SDH function.

{SDH} in brackets:

- Succinate ⇄ {

IIf ⇄ nFeS ⇄ IIq} ⇄ Ubiquinol ⇄ G3P

IIf ⇄ nFeS ⇄ IIq} ⇄ Ubiquinol ⇄ G3P

Forward electron flow (succinate → SDH)

Malonate [⊣IIf]: effective

- Succinate — {⊣IIf — nFeS — IIq}

(Targets the source, suppressing ROS.)

Atpenin [⊣IIq]: ineffective

- Succinate → {

IIf → nFeS — IIq⊢}

IIf → nFeS — IIq⊢}

(Targets the opposite site, leaving the source available, so ROS persists.)

Reverse electron flow (SDH ← ubiquinol)

Malonate [⊣IIf]: effective as before

- {⊣IIf — nFeS ← IIq} ← Ubiquinol ← G3P

(Targets the source, suppressing ROS.)

Atpenin [⊣IIq]: also effective

- {IIf — nFeS — IIq⊢} — Ubiquinol ← G3P

(Targets the opposite site where electrons would now enter, leaving the source inaccessible, suppressing ROS.)

The bars below confirm those outcomes:

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M112.374629)To compare values, a high succinate concentration (5 mM) yielded a H₂O₂ production rate of ~1.6 nmol/min/mg, decreasing to ~0.2 nmol/min/mg after adding the inhibitors (⊣Iq + ⊣IIIqo).

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M112.374629)Lowering the succinate concentration (from 5 mM) in the presence of inhibitors leads to an unexpected increase in ROS production again.

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M112.374629)This points to SDH as a possible ROS contributor at normal succinate concentrations, especially when electrons accumulate in the UQ pool. The peak of ~1.1 nmol/min/mg occurred at 0.4 mM succinate, which falls within the healthy, physiological range.

Succinate Concentration SDH Km (↓value  ↑affinity)

↑affinity)0.1–0.4 mM Health 0.2 mM (0.1–0.5 mM) Disease (inflammation, etc) 0.9–5 mM Ischemia 2–5 mM Experiments ≤10 mM Source: the internet.

Overall, SDH can generate ROS at rates that are comparable to (if not greater than) those of Complex I, in both forward and reverse operation, without needing extreme succinate concentrations.

The bulk of the increase in FAD-dependent respiration with fatty acids comes from ETFDH (FAD), but relative to glucose, SDH (FAD) also becomes more engaged because of greater TCA cycling. Electrons from fatty acids therefore enter the respiratory chain through Complex I, SDH and ETFDH, converging later on UQ.

Mobile carrier Respiratory complex Mobile Carrier Respiratory complex ETFH₂ → ETFDH

NADH →  Complex I →

Complex I →UQ →  Complex III

Complex IIISuccinate →  SDH

SDH

When the UQ pool receives more electrons than can be cleared through this conventional route, excess electrons tend to spill over from UQ to available complexes.

Because the redox potential of ubiquinol/ubiquinone (UQ pool) is closer to that of succinate/fumarate (SDH) than to NADH/NAD⁺ (Complex I), SDH is more prone to reverse electron flow. In line with that, when Complex III was inhibited in the guiding experiment, electrons from palmitoyl-carnitine escaped the UQ pool far more through SDH than through Complex I.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.006)In addition, Reverse Electron Transfer

through Complex I draws on part of the electrochemical pull across compartments to drive an unfavorable reaction, essentially undoing work that consumes energy.

through Complex I draws on part of the electrochemical pull across compartments to drive an unfavorable reaction, essentially undoing work that consumes energy.Forward e⁻ donor Respiratory complex Reverse e⁻ donor NADH → Complex I ← UQH₂ (+ energy) Succinate → SDH ← UQH₂ ETFH₂ → ETFDH ← UQH₂ FAD-dependent complexes need far less energy to reverse than Complex I.

When the respiratory chain is compromised at the level of Complex III and beyond, the electrochemical force may already be weakened, increasing reliance on Complex I alone to sustain it, making further drawing for reversal unlikely.

- In special cases, Complex V can also fill in to maintain the electrochemical force as an ATP hydrolase, sourcing ATP from SCS (in the TCA cycle) or the cytosol.

Electron escape from the respiratory chain through unconventional routes is not always accidental. A link between Complex I and SDH allows Complex I to operate in forward direction while electrons are cleared by SDH. Fumarate becomes a final electron acceptor as a substitute for oxygen that may be inaccessible or severely lacking.

Mobile carrier Respiratory complex Mobile Carrier Respiratory complex  ETFH₂ →

ETFH₂ →ETFDH

NADH →  Complex I →

Complex I →UQ or RQ ↛  Complex III

Complex IIISuccinate ←  SDH* ←

SDH* ←↲ - Succinate ←(*SDH)– Fumarate

This SDH reversal (using fumarate as an electron sink) is one of the explanations for succinate that accumulates during ischemia (when blood flow is interrupted). The fast oxidation of such succinate upon reperfusion (when blood flow is restored) then contributes to a massive ROS burst, primarily from Complex I.

Care is needed when comparing physiological reverse electron flow with pathological conditions that involve gross abnormalities, such as marked adenosine nucleotide depletion (impairing oxidative phosphorylation response), inability to wash out metabolites (from poor circulation), loss of barrier integrity, non-selective uptake of molecules, severe swelling and calcium overload. These ischemia-reperfusion disturbances make mitochondria more erratic in processing the sudden influx of nutrients (and oxygen) in addition to the accumulated metabolites.

And yet, we have reductive stress reductionists reducing everyday palmitate exposure to succinate that accumulates under ischemia, ignoring how each substrate is oxidized in contrasting metabolic states and relying solely on a flawed assumption that increased FAD-dependent respiration with fatty acids implies extreme engagement of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH).

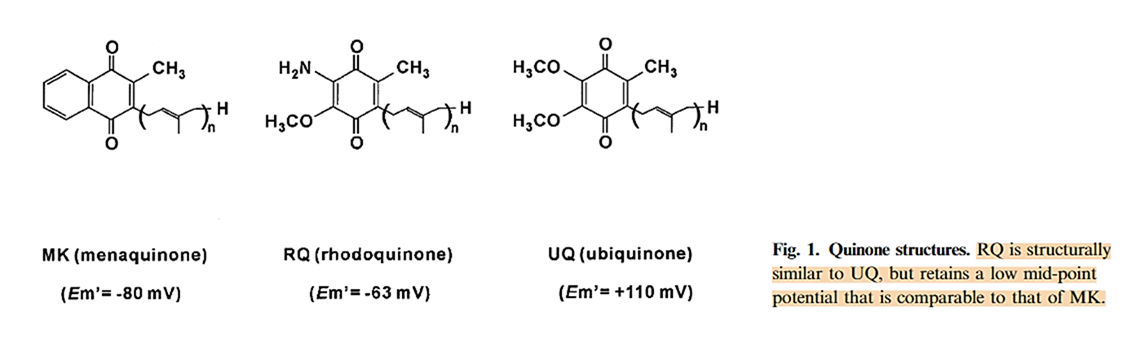

The same reductionists treat menaquinone-4 (MK-4) as an appropriate substitute for ubiquinone-10 (UQ-10), disregarding differences in head-group and tail as if they were irrelevant.

Ubiquinone emerged after menaquinone and became the dominant quinone in eukaryotes. The human respiratory chain is evolutionarily optimized for the properties of UQ-10, and it's unlikely that cells would undergo convoluted steps to lengthen its tail if that were futile.

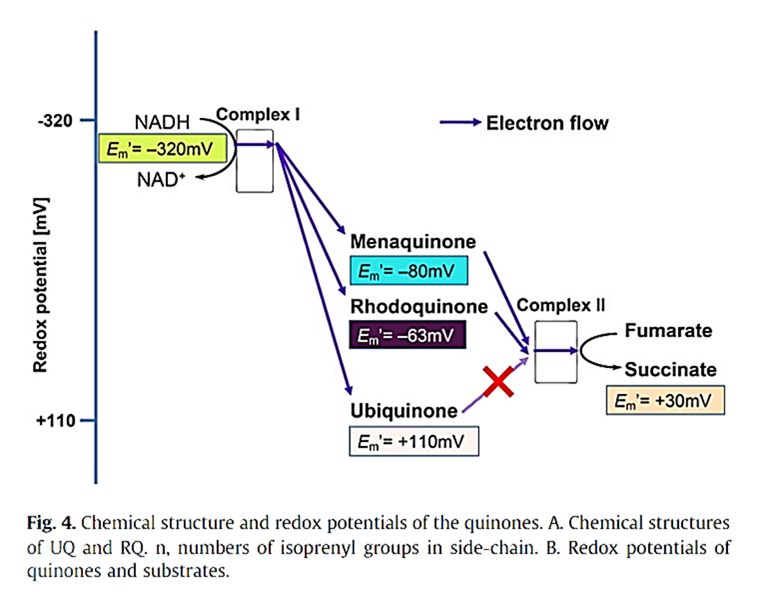

Head-group potential:

⠀(10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03553.x)Low-potential quinones (menaquinone and rhodoquinone) are better promoters of reverse electron flow relative to the high-potential ubiquinone.

⠀(10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.013)Moreover, their low redox potential suggests that these alternative quinones are poorer electron acceptors, making forward transfer less favorable. This skewing (evident for MK at a higher level than SDH in the graph above) may impair the activity of all primary respiratory complexes and also that of Complex III, which needs quinones as electron acceptors at its inner quinone site.

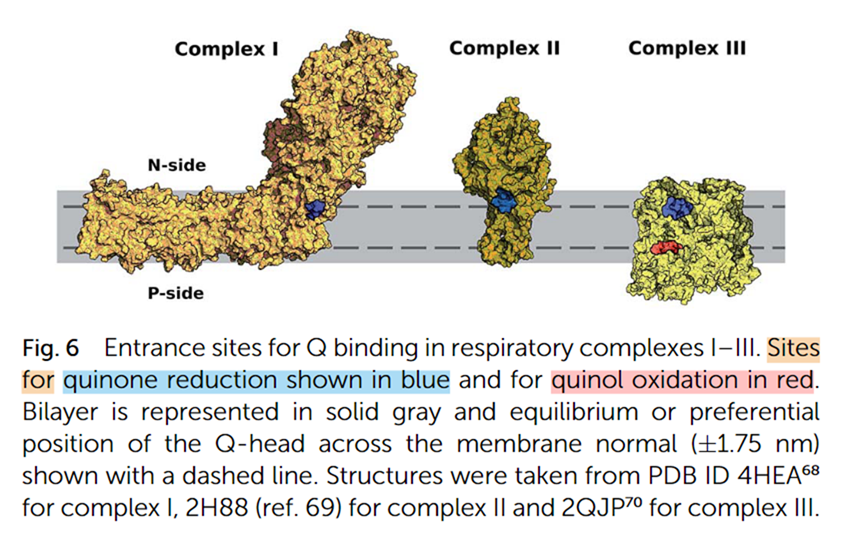

Tail length and membrane anchoring:

Quinones with shorter tails have lower lipid affinity, so the decreased length together with the lower affinity prevents proper quinone anchoring to the membrane core (midplane). Because the head-group must alternate between the quinone-binding cavities on opposite planes (dashed lines below), loss of anchoring makes its movement unguided and more uncertain.

⠀(10.1039/C9RA01681C)- Blue: quinone reduction site

- Red: quinone oxidation site

The quinone head-group (not shown) keeps switching between reduction and oxidation sites (at upper and lower dashed planes), anchored at the membrane midplane.

This plane switching occurs in respiration involving Complex I, SDH, ETFDH, and other complexes that have inner-sided quinone sites, but not in GPDH and DHODH, which operate from the exterior, having their quinone sites already aligned with the outer plane.

Therefore, MK-4 combines two concerning traits: it's a low-potential, short-chain quinone, whereas UQ-10 is a high-potential, long-chain quinone. Many microbes synthesize longer-chain quinones to meet their electron-carrying needs, as reflected in the composition of fermented foods. If MK-4 were to substitute for UQ-10 in humans, its use would imply reliance on a quinone that even microbes relegate, risking chronic inefficiency in electron transfer (already a problem at the level of Complex III) and higher ROS production upstream of the impairment.

Having discussed SDH in relation to fatty acids and quinones within the respiratory chain, we next turn to KGDHc, a mitochondrial matrix complex that precedes SDH by a few metabolic steps and is another ROS producer.

-

KGDHc has extraordinary ROS-producing capacity among mitochondrial matrix enzymes

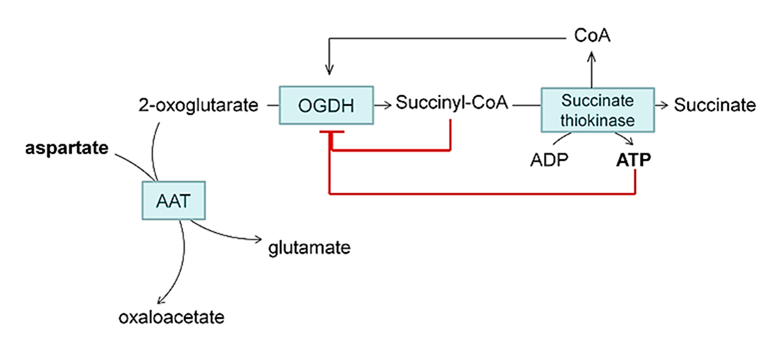

Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (KGDHc) is a group of enzymes in the TCA cycle that function together to oxidize ketoglutarate.

KGDHc is also abbreviated OGDHc (oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex). α-ketoglutarate and 2-oxoglutarate are synonyms; the prefixes can be dropped in everyday use, leaving implicit that the term refers to the most relevant variant. I'll rely on oxoglutarate when needed for consistency, but ketoglutarate is often preferable because it helps to differentiate from related names such as oxaloacetate and oxoacids.

KGDHc belongs to the oxoacid dehydrogenase complex family. Within this family, KGDHc has by far the highest ROS-producing capacity, followed by PDHc.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001)Oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes therefore show far more ROS potential than the flavin site of Complex I ('If'), but not more than its quinone site ('Iq').

Nevertheless, it's possible for KGDHc to exceed the ROS production of both Complex I sites in non-peak conditions.

Despite its abundance in mitochondria and a high ROS-producing capacity, KGDHc is usually not a major ROS contributor. However, certain conditions can bring out part of this capacity, and a fraction of ROS that's attributed to the flavin of Complex I may instead come from the flavin subunit of KGDHc, which also interacts with the NAD pool.

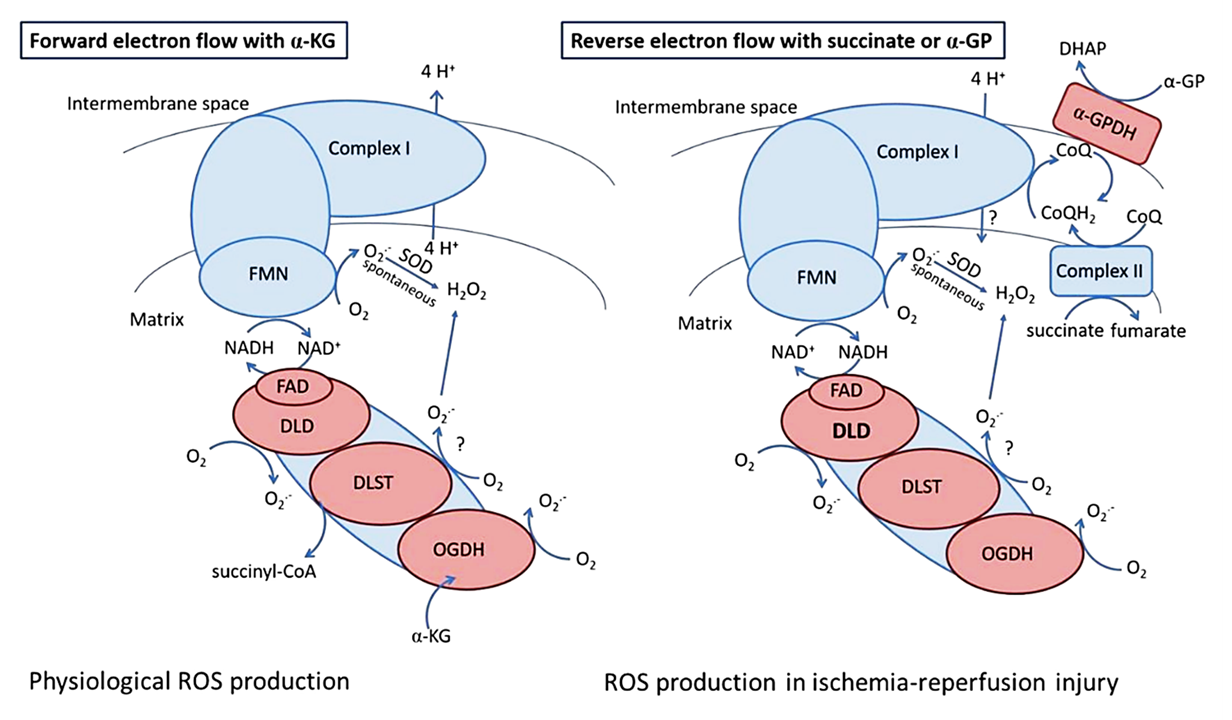

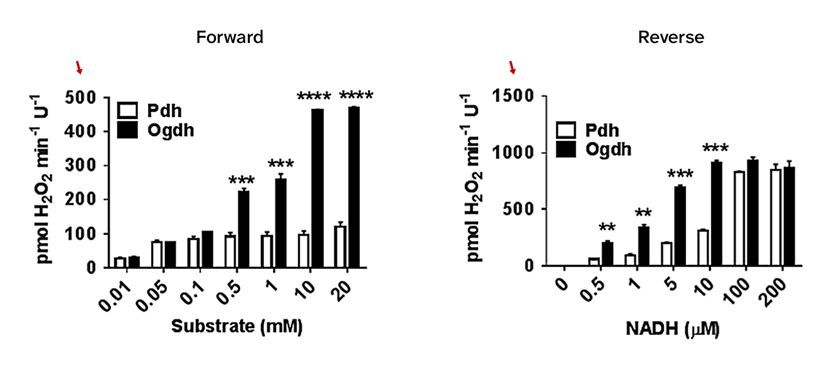

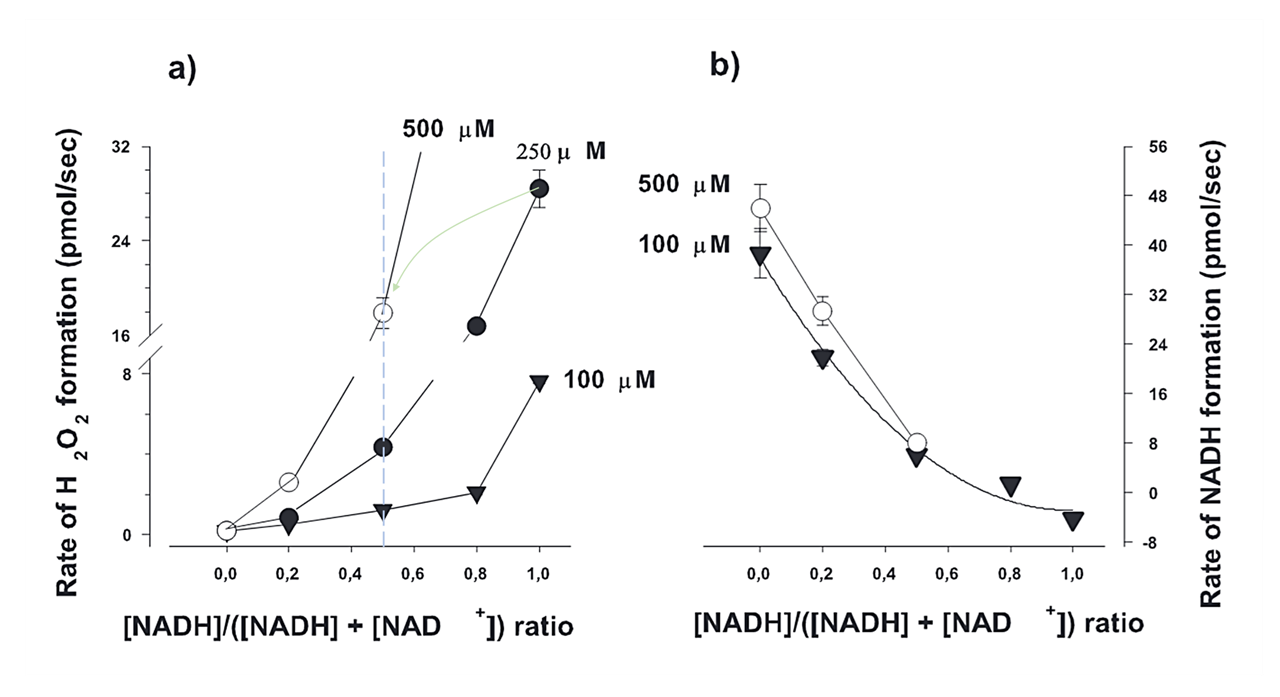

KGDHc (and other family members) can generate ROS during forward and reverse electron flow.

⠀(10.3390/antiox11081487)Out of its multiple subunits with leakage potential...

- E1o (OGDH)

- E2o (DLST)

- E3 (DLDH)

...the flavin-containing E3 is the most established source. E3 is common to oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes, which is why it lacks the "o" (oxoglutarate) specifier.

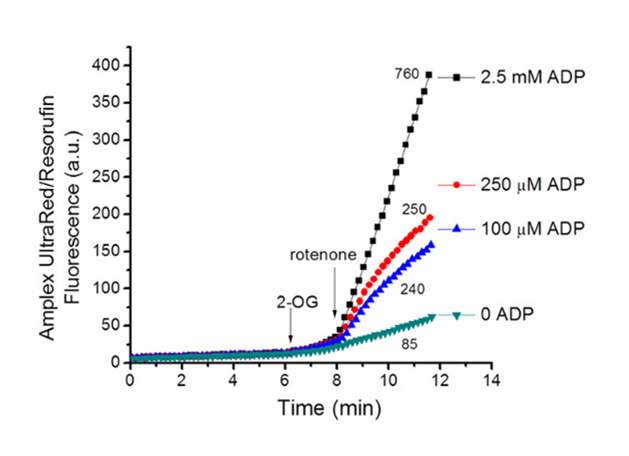

The first stage of KGDHc's activity (decarboxylation at 'OGDH') is irreversible, so electrons can't fully flow back and regenerate ketoglutarate ('α-KG').

KGDHc uses NAD⁺ as the terminal electron acceptor in its normal function. If NAD⁺ becomes limiting or NADH occurs in excess, KGDHc starts to overproduce ROS.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.06.014)- Pyruvate → PDHc ⇄ NADH

- Ketoglutarate → KGDHc ⇄ NADH

Ketoglutarate and NADH can serve as electron donors to KGDHc, and both are normally present together. When NADH rises at the expense of steady NAD⁺ levels, ROS overproduction may simply result from an inability to clear electrons during forward KGDHc operation, inducing more electrons from ketoglutarate to escape the complex via O₂. This is likely the prevalent way that electrons leak from KGDHc, rather than through frank backflow from NADH.

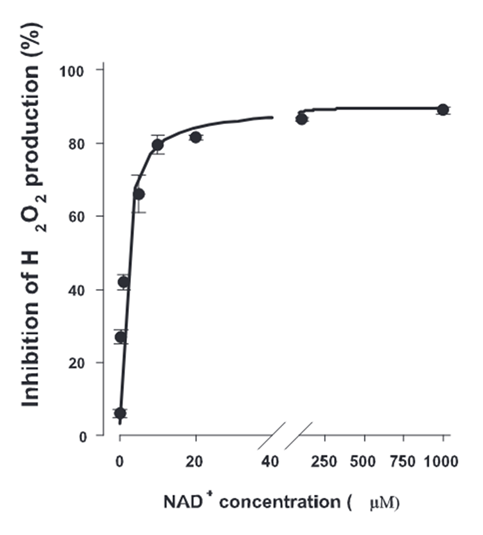

Increasing the NAD⁺ availability inhibits ROS production:

⠀(10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1842-04.2004)However, the electron load of NAD pool can decrease through either expansion (which dilutes NADH) or clearance.

Condition NADH/NAD⁺ Ratio Achieved via Total NAD 10NADH / 10NAD⁺ 1 (reference) 20 NAD 10NADH / ↑40NAD⁺ 0.25 expansion ↑50 NAD ↓4NADH / ↑16NAD⁺ 0.25 clearance 20 NAD Niacin (and its derivatives) supplementation expands the capacity to accept electrons with extra NAD⁺, yet it doesn't address what caused electrons to accumulate. This extra NAD⁺ may indirectly relieve the inhibition of oxidative pathways, but only to some extent.

At a fixed NADH/NAD⁺ ratio, ROS production might rise with the total NAD concentration, as represented by each curve below:

⠀(10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1842-04.2004)This way, additional NAD⁺ offers a temporary solution, but without improving electron clearance, electrons could accumulate in the NAD pool again, becoming increasingly problematic as the pool expands.

Overloading cells with niacin without considering the fate of electrons that NAD⁺ accepts assumes a positive outcome. Yet, NAD transfers electrons from matrix dehydrogenases to the respiratory chain, which contains major ROS-producing sites in complexes susceptible to dysfunction. Extra NAD could conceivably risk pushing more electrons into an already burdened pathway, shifting them from a milder to a harsher ROS producer.

- For example, rather than electrons leaking at KGDHc, NAD could possibly transfer them to leak at the quinone site of Complex I.

In practice, extra NAD doesn't increase ROS production. It is the flavin of Complex I that equilibrates with the NAD pool:

- KGDHc(Kf) ⇄ NAD ⇄ (If)Complex I

Yet, site If has modest ROS-producing capacity compared with upstream enzymes such as KGDHc and PDHc, so clearing electrons away from riskier sites is a preferable immediate strategy.

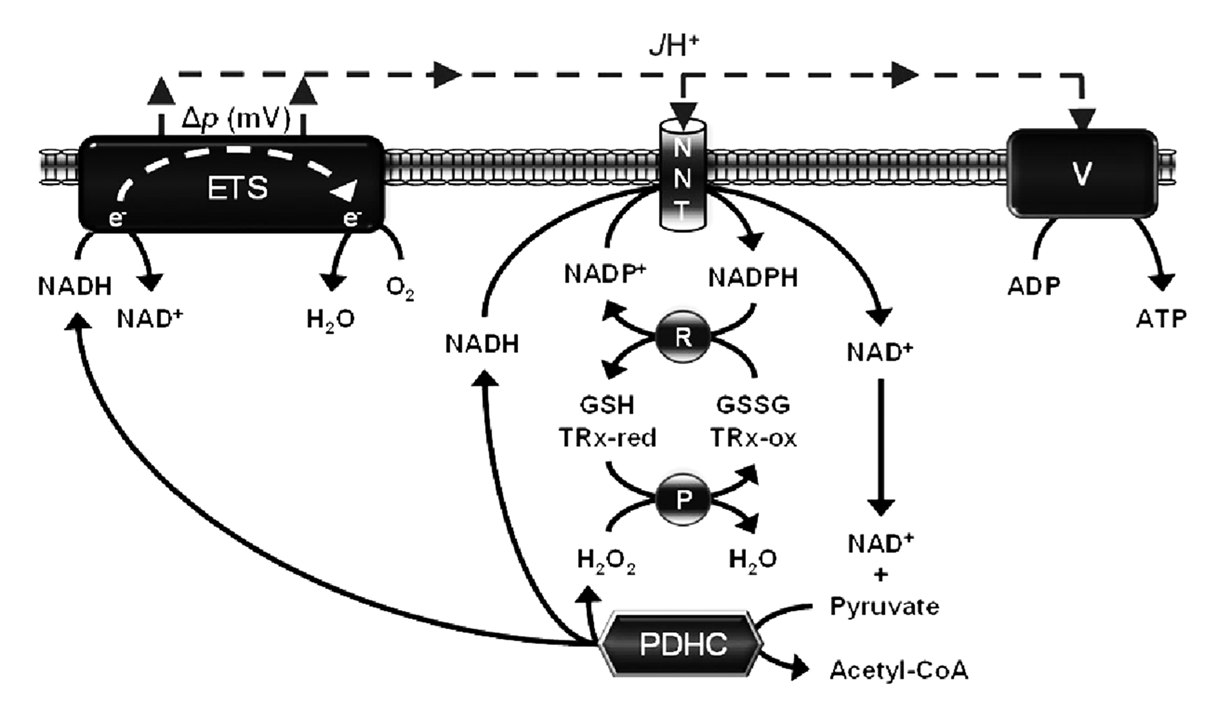

In addition, once electrons enter the NAD pool, they don't need to be transferred to the respiratory chain. A fraction can be diverted to NADP, preventing further leakage while boosting the antioxidative capacity to neutralize ROS from such leakage.

⠀(10.1042/BJ20141447)- NADH + NADP⁺ (+ H⁺out) ⟶ NAD⁺ + NADPH (+ H⁺in)

The H⁺-dissipating effect (out → in) of NNT is minor, but needed to drive an otherwise unfavorable electron-transfer reaction (NADH ↷ NADP⁺), and becomes limited when the external H⁺ concentration is low. Misuse of mitochondrial uncouplers can compromise this important means to NADPH.

Other NAD-dependent enzymes can also operate in reverse, contributing to redirect electrons into stable metabolites without generating ROS.

Moreover, oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes (such as KGDHc and PDHc) can associate with Complex I, supporting channeled electron transfer. This efficient hand-off creates a more dedicated NAD pool that's less affected by matrix fluctuations, helping the associated enzymes to selectively draw or exclude either NAD⁺ or NADH as needed. Electron backflow may be prevented if their association keeps excess NADH unavailable to KGDHc.

These considerations support niacin supplementation, because extra NAD⁺ expands the capacity to clear electrons from problematic matrix sites, directing them into safer pathways and allowing enzymes to selectively exploit the NAD pool if it becomes overloaded. In any case, NAD synthesis and degradation are regulated processes that are difficult to override.

Fatty acid oxidation is more dependent on the TCA cycle, raising the need for KGDHc.

Fatty acids Glucose PDH - ⅓ ↝CO₂ ↑↑ IDH ½ ↝CO₂ ⅓ ↝CO₂ ↓ KGDH ½ ↝CO₂ ⅓ ↝CO₂ ↓ This greater dependence on KGDH is intensified by the lower energetic efficiency with fatty acids, making them more demanding on UQ as well. Also, the NAD oxidation state is similar for fatty acid oxidation and for glutamate + malate (NAD-oriented substrates).

⠀(10.1016/j.redox.2013.04.005)Such factors suggest that fatty acids increase the electron load on KGDHc, which may amplify leakage in dysfunctional scenarios, especially because the offloading rate remains unchanged.

ATP/ADP and succinyl-CoA/CoA affect KGDHc activity:

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M113.545301)(Aspartate is used in experiments to divert ketoglutarate away from KGDHc.)

Interestingly, when KGDHc is overproducing ROS, elevating ADP levels (typically ROS-suppressive for the respiratory chain, as occurs in exercise) may actually lead to further ROS production. ADP raises KGDHc's affinity for ketoglutarate (affecting 'E1o'), promotes succinyl-CoA removal and releases CoA (affecting 'E2o'), which counteract the protective inhibitions shown above.

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M113.545301)Rotenone blocks Complex I, abruptly eliminating the main outlet for electrons in the NAD pool, making it impractical to reroute all those electrons without perturbing a fixed-size pool. This perturbation impairs KGDHc activity, reflected in greater leakage.

Like other oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes, normal KGDHc activity involves sulfur-containing residues (in the E2 and E3 subunits, and in CoA). The redox state of mitochondria modifies these residues, offering an extra layer of control that adjusts activity in response to elevated ROS. However, thioredoxin (as an antioxidant) can sometimes interfere with this regulation by suppressing radical-mediated communication between subunits, which may inadvertently prevent inactivation of the complex.

Nevertheless, a priority for KGDHc is to prevent electron back-pressure at its terminal subunit by increasing the availability of NAD⁺, preferably through NADH reoxidation. Otherwise, insufficient NAD⁺ relative to NADH makes KGDHc prone to entering the ROS-overdrive mode, whether in forward (prevalent) or reverse function.

While emphasis has been on fatty acids and glucose, amino acids are also constantly oxidized for energy, not only when consumed in excess or in severe catabolic states, accounting for about 15% of daily caloric needs. Tissues expressing BCKDHc (leu, ile, val) and KADHc (lys, trp) may then produce slight additional ROS from these complexes, although experiments suggest that it's of secondary importance.

The ETF pathway as a likely ROS source during mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation

A fraction of H₂O₂ remained unassigned when palmitoyl-carnitine was oxidized in the absence of respiratory chain inhibitors or in the presence of myxothiazol (⊣IIIqo).

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.006)The source of this H₂O₂ is still unclear, but a protein of the ETF (Electron-transfer Flavorprotein) pathway is a likely candidate because the main suspects have already been accounted for (as covered in previous sections).

Fatty acid β-oxidation and the ETF pathway:

Step in β-oxidation Enzyme (β-oxidation) Electron carrier Enzyme (respiratory chain) Fatty acyl-CoA

1. First oxidation (peroxisomes) (FAD) ACOX

→O₂→H₂O₂ 1. First oxidation (mitochondria) (FAD) ACADHs

←  ETF→

ETF→{  }ETFDH

}ETFDH↓ 2. Hydration (oxygenation) (H₂O) ECH 3. Second oxidation (NAD⁺) HADH ←NAD→ Complex I 4. Cleavage (CoA) KAT

2 Acyl-CoA ACOX, Acyl‑CoA oxidase; ACADH, Acyl‑CoA dehydrogenase; ECH, Enoyl‑CoA hydratase; HADH, Hydroxyacyl‑CoA dehydrogenase; KAT, Ketoacyl‑CoA thiolase; ETF, Electron-transfer Favorprotein; ETFDH, Electron-transfer Flavoprotein dehydrogenase (also called ETF:Q–OR, Electron-transfer Flavoprotein–to–Quinone oxidoreductase).

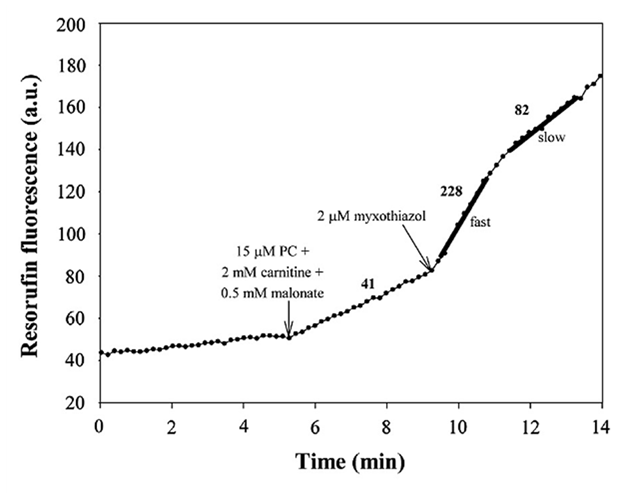

Palmitoyl-carnitine oxidation in the presence of malonate (⊣SDH) rules out SDH as a confounding ROS source (hashed bars in the previous graph). Further addition of myxothiazol (⊣IIIqo) intensifies the unassigned ROS signal in two phases: a burst and a post-burst phase.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.006)The values next to each segment represent ROS production rate.

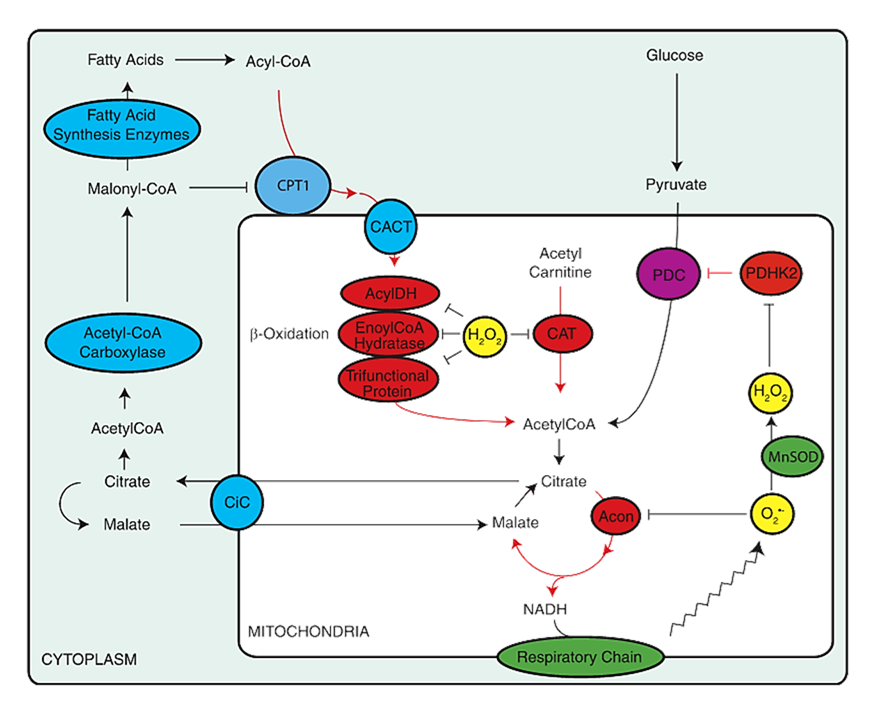

With Complex III inhibited, the UQ pool becomes overloaded with electrons, preventing ETFDH from clearing them from preceding reactions and compromising the entire pathway.

- Fatty acyl-CoA → ACADH ⇄ ETF ⇄ ETFDH ⇄ UQ ↛

Complex III

ETFDH can run in reverse, and an overloaded Q pool may promote reverse electron transfer from the respiratory chain. But because fatty acid β-oxidation is less constrained than the TCA cycle, the forward pressure on ETFDH is greater than on SDH, making electrons more likely to escape the UQ pool through SDH instead of ETFDH.

Although ETFDH contains an iron-sulfur cluster, a flavin, and a quinone-reacting site, all of which could generate ROS, these redox centers seem protected from oxygen in the enzyme, rendering it a less likely ROS source. This leaves ACADHs and ETF as more probable mitochondrial contributors.

The authors propose that the unexplained ROS fraction comes from ETF, and that the two phases reflect changes in the electronic state of ETF, possibly while interacting with ACADHs.

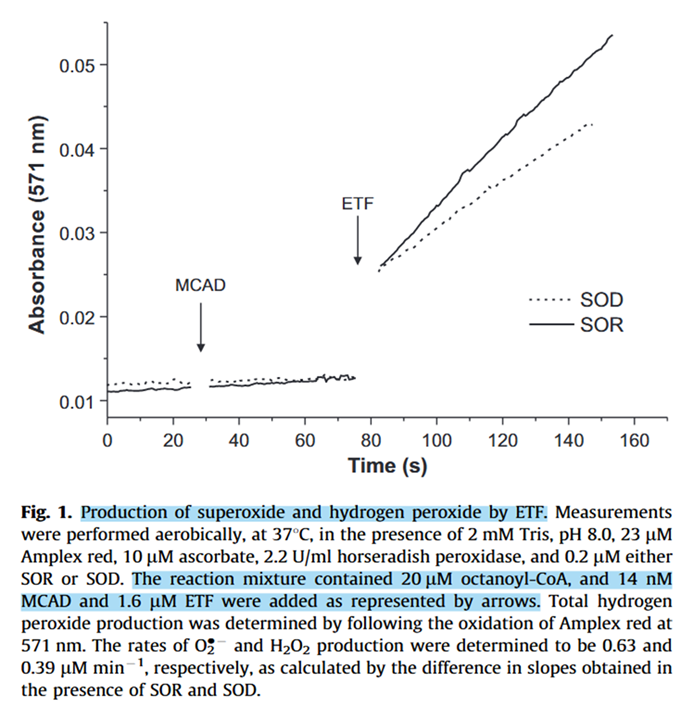

Experiments with purified ETF support its role as a ROS producer.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.016)- Superoxide reductase (SOR): 1O₂•⁻ → 1H₂O₂

- Superoxide dismutase (SOD): 2O₂•⁻ → 1H₂O₂ + 1O₂

Medium-chain Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) was added to oxidize octanoyl-CoA (8-carbon fatty acyl; the activated form of octanoic, caprylic, or goatic acid).

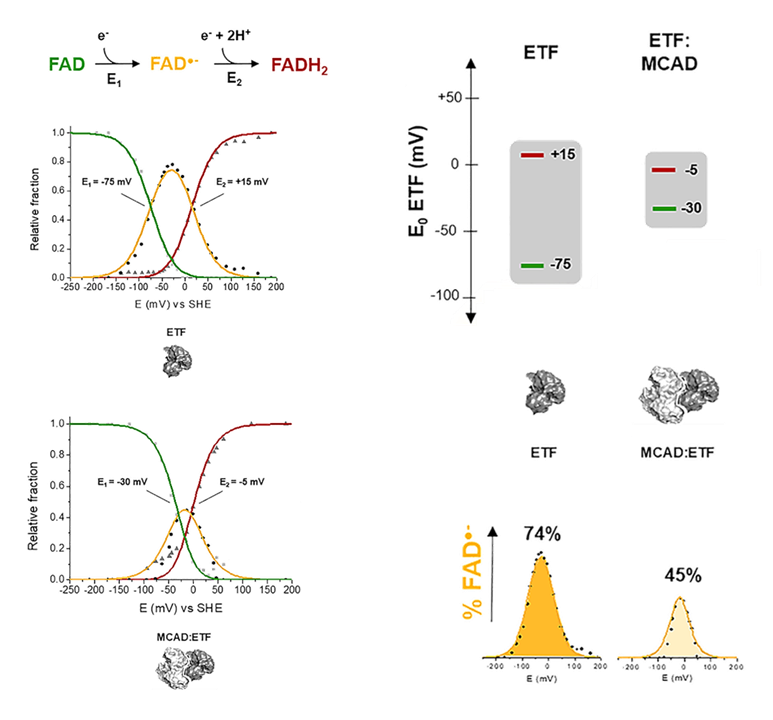

Contrary to NAD, which accepts a pair of electrons from dehydrogenases simultaneously, ETF receives electrons from ACADHs in sequence: the first transfer is fast, and the second slower.

NAD

- 2e⁻ + NAD(ox) ⟶ NAD(red)

ETF

- 1e⁻ + ETF-FAD(ox) ⟶ ETF-FAD(½red) — fast

- 1e⁻ + ETF-FAD(½red) ⟶ ETF-FAD(red) — slow

Any condition that delays the second transfer may prolong the ACADH-ETF interaction, giving flavin intermediates more time to leak electrons to available O₂ and emit ROS.

The authors also speculate that ETFDH impairment caused by excess electrons in the UQ pool affects the upstream dynamics of the second transfer, explaining the burst phase of ROS production, and that the post-burst phase appears when the ETF pathway is so overloaded that partial reduction becomes unfavorable; fully reduced flavins are less reactive with O₂.

ACADH and ETF can form a complex that enhances complete electron transfer. Their association narrows the redox midpoint potential difference between the first and second half-reactions, lessening the advantage of the first transfer and resulting in a more simultaneous reaction sequence.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.016)In addition to lowering radical occurrence, the ACADH-ETF complex limits O₂ access, further preventing ROS formation.

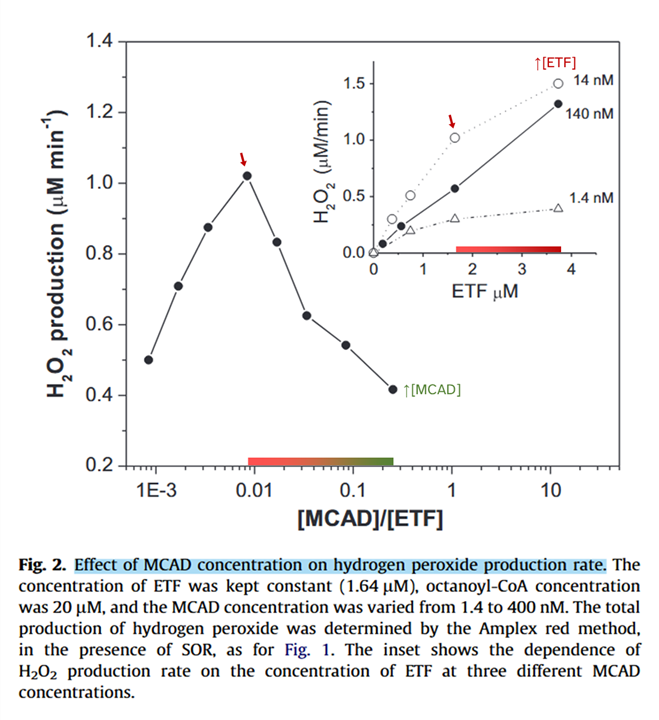

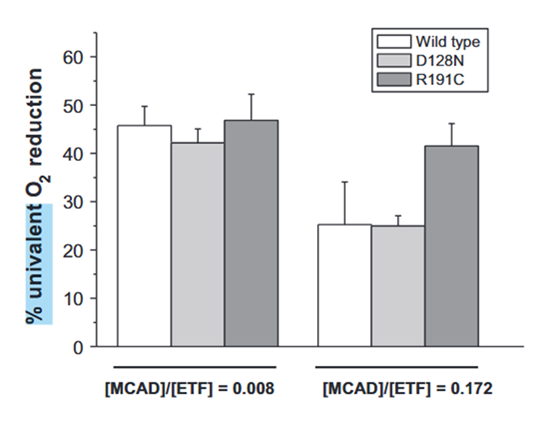

A higher ACADH/ETF ratio tends to minimize ROS production.

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.016)Increasing ACADH concentration suppresses ROS, whereas increasing ETF raises it (inset). Because ACADH is the electron donor, low concentrations may decrease ROS by limiting electron supply.

The higher ACADH/ETF ratio minimizes overall ROS production and also the proportion of one-electron leakage:

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.016)Even though higher ACADH concentrations may prevent ROS from ETF, ACADHs themselves can also be a source.

The first oxidative step of peroxisomal β-oxidation uses ACOXs (oxidases), whereas mitochondrial β-oxidation uses ACADHs (dehydrogenases). Oxidases are inherent ROS producers, so ACOX releases H₂O₂ on every enzyme cycle. Although dehydrogenases don't rely on O₂ as a primary electron acceptor, ACADHs may retain partial oxidase activity, behaving like ACOXs and generating H₂O₂.

Peroxisomal β-oxidation:

- ACOX + (ECH + HADH + KAT)

- ↳

O₂

O₂

- ↳

Mitochondrial β-oxidation:

- ACADHs + (ECH + HADH + KAT)

- ↳ ETF ↴

- ↳

O₂

O₂

This partial oxidase activity represents only a small fraction of the total ACADH activity, yet it can be a significant ROS source inside mitochondria.

⠀(10.1016/j.gene.2021.145407)- H2O2 release from the very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD)

- The fatty acid oxidation enzyme long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase can be a source of mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide (LCAD)

ACADHs share structural similarities with ACOX, and the larger cavity of ACADHs adapted to longer-chain fatty acids offers poorer FAD protection from oxygen, which might explain why ACADHs dedicated to shorter chains don't generate ROS. Among ACADHs, only VLCAD and LCAD associate with the mitochondrial membrane, and this proximity to an oxygen-rich environment may contribute to their higher ROS production.

For example, in the octanoyl-CoA experiment above they used MCAD (medium-chain ACADH), which was ineffective until ETF was added, triggering the sharp ROS rise.

In parallel, ACAD9 (⇈) hints at potential disturbances at Complex I when the ETF electron pathway is stressed, which could compound with issues from excess fatty acid release:

ETF and ACADHs with partial oxidase activity are therefore the likely origins of the remaining ROS, concluding our discussion on individual ROS sources important to fatty acid oxidation.

-

Simultaneous oxidation of semi-physiological substrate mixtures

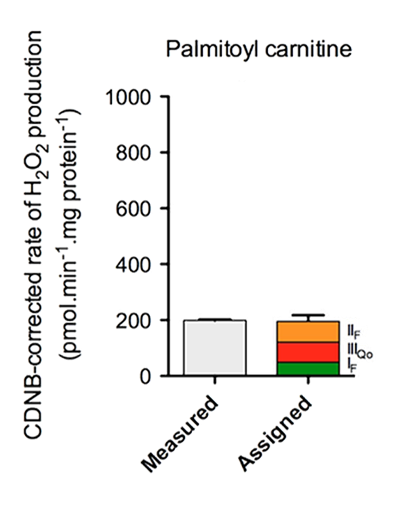

Mitochondria encounter mixtures rather than single substrates, so incubating them with a comprehensive blend that reflects reported intracellular concentrations leads to a more realistic response.

Palmitoyl-carnitine alone

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001)⠀Palmitoyl-carnitine in isolation, as shown previously.

Palmitoyl-carnitine as part of a semi-physiological mixture

⠀(10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001)⠀Semi-physiological mixture that includes palmitoyl-carnitine, extra carnitine, TCA cycle metabolites, amino acids, ketone bodies, glycerol-phosphate, etc.

The comparison clearly shows that the substrate mixture yields higher ROS rates and suggests some degree of interference between electron flows, supporting the notion that mitochondria are capable of metabolizing a variety of substrates simultaneously.

Nutrient preferences vary across tissues, and a cell typically oxidizes the most abundant substrates reflecting those preferences. But within a cell, mitochondrial subpopulations and the cristae of individual mitochondria (where respiratory enzymes are concentrated) can still specialize differently. As a consequence, assuming substrate oxidations were mutually exclusive in a pathway, that diversification would make simultaneous oxidation possible in the same cell.

"[..]in the presence of concentrations of fatty acids and ketone bodies found during fasting, glucose transport is inhibited by 30% and PFK-1 by 50–75%, whereas glucose oxidation is almost, but not completely inhibited."

(10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580277.x)

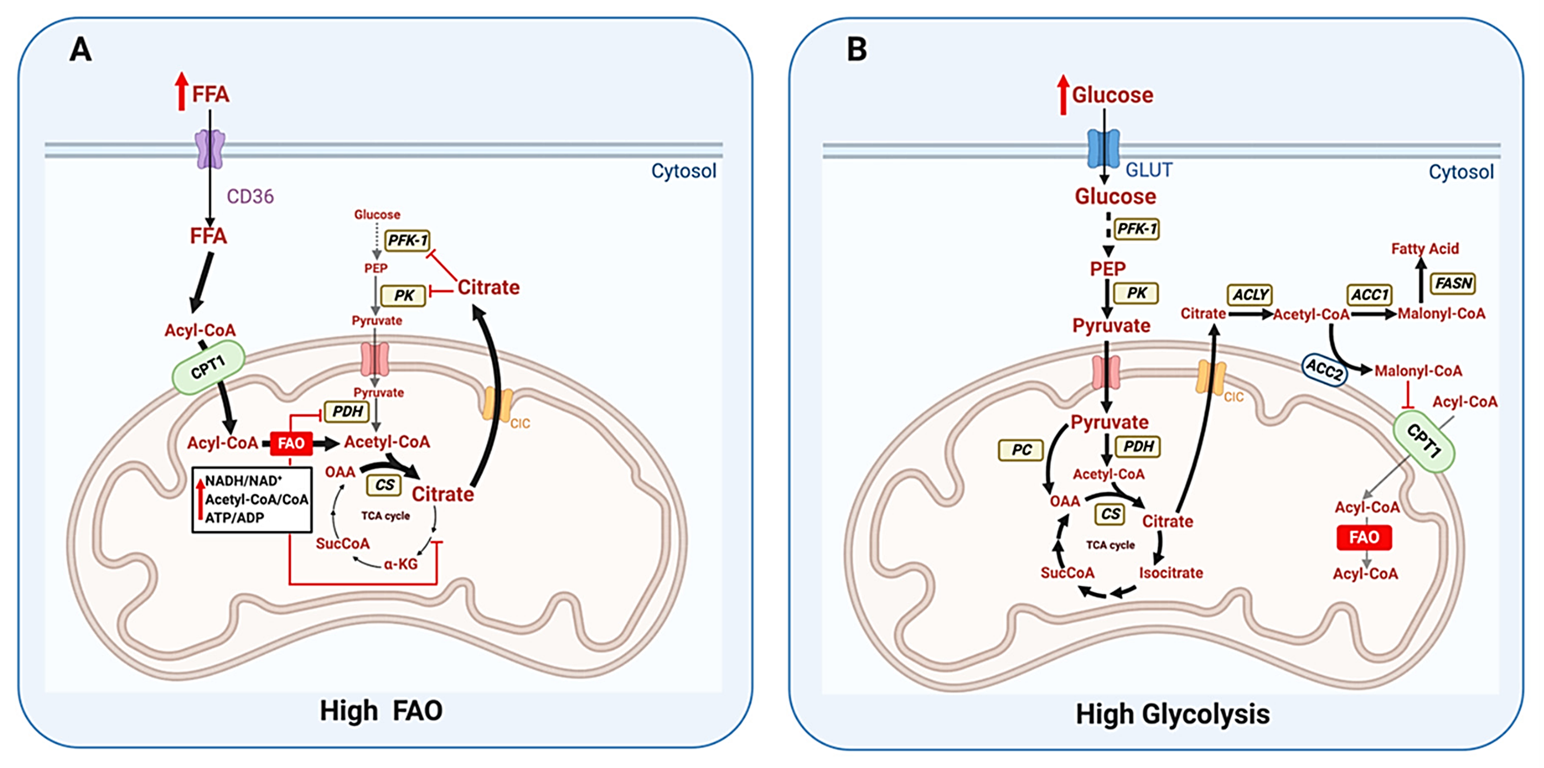

Moreover, the mixture above omitted glucose because it's spared at rest, but the inhibitory controls that drive the glucose–fatty acid (Randle) cycle can be avoided when needed. For example, ATP shortage can relieve the classic inhibition of the primary enzyme of fatty acid import (CPT1).

⠀(10.3390/cells9122600)ATP depletion (↓ATP/↑AMP) and other factors can activate AMP kinase, which then:

- Inhibits fatty acid synthesis (no malonyl-CoA by ACC1 for 'FASN')

- Disinhibits fatty acid import for oxidation (no malonyl-CoA by ACC2 near CPT1)

- Enhances both effects in promoting residual malonyl-CoA clearance by MCD

⠀(10.1155/2022/2339584)Increasing substrate oxidation may elevate ROS, but mitochondria keep sensitive targets at metabolic turning points. As an example, the Fe-S cluster of aconitase (citrate ⇄ isocitrate) is very susceptible to O₂•⁻ attack, which can release Fe into the matrix and lead to unwanted reactions. Yet, aconitase acts early in the TCA cycle when acetyl-CoA is the substrate, so its heightened ROS sensitivity makes it a predictable target to sacrifice, diverting nutrients from complete oxidation and limiting electron supply.

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M112.400002)In contrasting scenarios, AMP kinase promotes mitochondrial oxidation, whereas ROS-sensitive targets are suppressing oxidation while preserving substrates. As with many diverting measures, chronic reliance on them tends to come with drawbacks.

The TCA cycle can continue to run in a truncated mode (glutamate clears inhibitory oxaloacetate in converting to ketoglutarate, which then feeds directly into KGDHc), contributing to a minimum viable electron supply; however, this function can also be inhibited when ROS become overwhelming.

Nevertheless, a substrate shift that generates a ROS surge can trigger adaptive remodeling of respiratory complexes, changing them into a less stressful arrangement better suited for the prevailing substrates. For instance, ROS can degrade Complex I and dissociate it from its supercomplex with Complex III and IV, releasing them to support FAD-dependent respiration more efficiently.

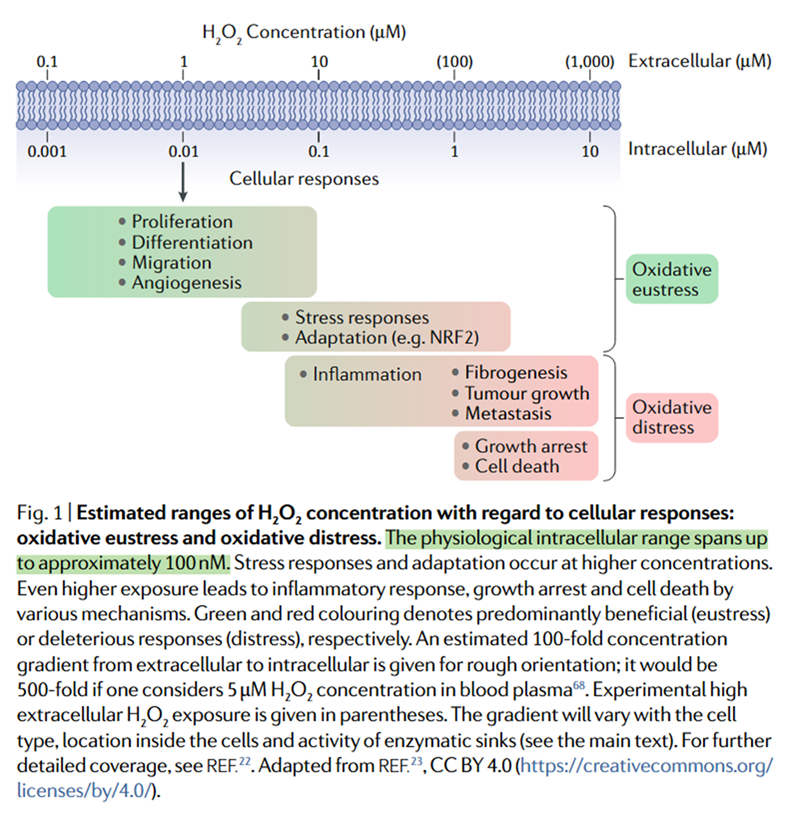

Beneficial effects are typically induced by controlled ROS exposure within a concentration range regarded advantageous. As the ROS concentration increases, desirable effects can still occur, but they become more variable and context-specific. For example, in some situations, forceful growth arrest or cell death is the preferable outcome.

⠀(10.1038/s41580-020-0230-3)Overall H₂O₂ levels inside cells and mitochondria might stay below 20 nM. Brief spikes can raise these levels into the low-µM range, serving as signals for adaptation, whereas excessive or sustained elevations often lead to disorder.

Despite marked individual variability, increasing reliance on fat oxidation involves less efficient electron use and generally raises ROS production compared with carbohydrate oxidation, which can further amplify ROS rates in predisposed states. However, without such predisposition and on balanced diets, the rates remain manageable because humans are well-adapted to metabolizing fats.

Conversely, lipid overload from excess fat consumption, adding to the existing pool of substrates and sometimes compounded by exaggerated storage release, promotes ROS overproduction and primes cells to generate even more ROS. That overload contrasts with conditions that shaped much of our evolution, which involved limited food and more frequent physical activity.

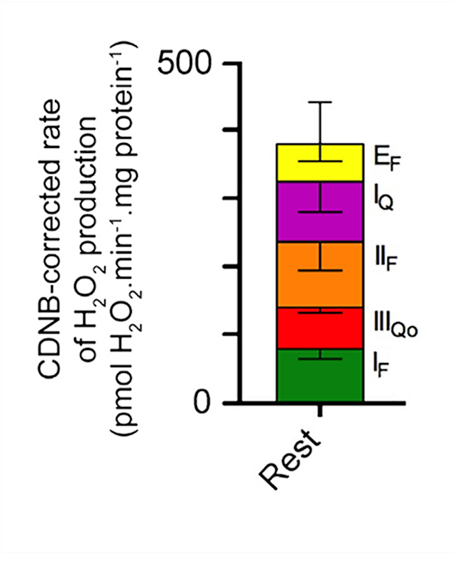

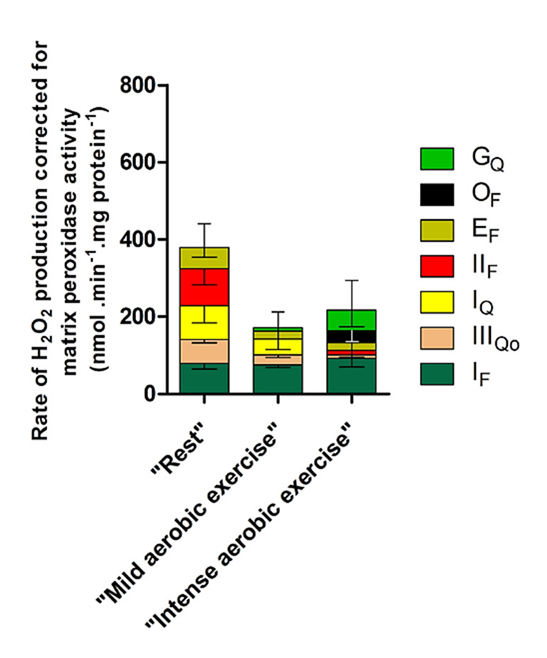

As expected, ROS output decreases under stimulated states, and this decrease is reflected in the profiles of most contributors:

⠀(10.1074/jbc.M114.619072)Condition Sources Rest IIf > Iq > If > IIIqo > Ef Mild exercise If ≫ Iq > IIIqo > Ef > Gq Intense exercise If ≫ Gq ≫ Of > Ef > IIf > IIIqo Bioenergetic quantum coaches' fixation on Complex I therefore has some validity, but recognizing Complex I (with its flavin and quinone sites) as a major contributor in more physiological conditions now comes from a comparison of sources, not from misconceptions and unawareness of alternatives.

With a lagging Complex III, electrons can build up in the UQ pool from multiple origins, including NAD-linked substrates. Complex I then experiences competing forces from both ends:

- NADH → {Complex I} ← UQH₂ (+ energy)

Forward Complex I operation is favored, more so because oxidizing many NAD-linked substrates in a row puts pressure to drive electrons downstream, and it takes atypical conditions (beyond excess UQH₂) to overcome that bias. Nevertheless, Complex I in forward operation can produce just as much ROS from its high-capacity quinone site as when it operates in reverse.

⠀(10.1042/BCJ20220611)So we don't need to invoke extensive reverse electron flow through Complex I to explain ROS rise from its rotenone-sensitive quinone site, nor suppose that succinate would be needed to induce it.

Recall also that most of the FAD-dependent respiration increase from fatty acids engages ETFDH rather than SDH. In contrast, reperfusion often involves a sudden oxidation of accumulated succinate, which has limited metabolic fates aside from SDH and bypasses many checkpoints. Although the oxidation of fatty acids can generate more ROS than that of accumulated succinate, this again needs unusual conditions.

- Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and oxidative stress: Lack of reverse electron transfer-associated production of reactive oxygen species

- Fatty acids decrease mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species at the reverse electron transport but increase it at the forward transport

Based on the results so far, if a substrate mixture raises ROS production in the presence of palmitate and the rate drops when oxidized separately, the concern is reciprocal: fatty acids affecting other fuels, but also other fuels affecting fatty acid oxidation.

- Mixture + palmitate → ↑ROS

- Mixture → ↓ROS

- Palmitate → ↓ROS

The ROS linked to fat metabolism can arise partly from parallel effects, such as structural or functional perturbations and up-regulation of alternative ROS-producing enzymes (NOX, XO, COX, LOX, CYP2, etc.). Examples:

- Fatty acids as modulators of the cellular production of reactive oxygen species

- Mitochondrial Overload and Incomplete Fatty Acid Oxidation Contribute to Skeletal Muscle Insulin Resistance

- Arachidonic acid interaction with the mitochondrial electron transport chain promotes reactive oxygen species generation

- Rotenone-like Action of the Branched-chain Phytanic Acid Induces Oxidative Stress in Mitochondria

Some of those perturbations occur before downstream pathways become overloaded with electrons and involve issues related to pantothenic acid rather than riboflavin.

Expanding on the earlier point, even-chain fatty acids produce acetyl-CoA, so oxaloacetate must be regenerated in the TCA cycle at a comparable rate to prevent acetyl-CoA buildup. Lipid oversupply creates a mismatch, letting excess acetyl-CoA product-inhibit the final β-oxidation enzyme (KAT) while sequestering CoA, further impairing its activity. As a result, the pathway becomes jammed, accumulating incomplete β-oxidation intermediates that disturb normal mitochondrial oxidation and deprive other enzymes of shared cofactors. Carnitine may export unwanted metabolites, and alternative thiolases release CoA, but both processes have limited capacity to compensate.

Such derangement also lowers citrate, which is how mitochondria communicate substrate abundance to the cytosol and feedback-inhibit additional fatty acid import, making it a self-perpetuating issue.

Altogether, these parallel effects may represent a portion of the ROS fraction from fatty acids that mitochondrial uncouplers can't relieve. They become concerning on diets that are excessively high in fat and should not be lumped together with incidental leakage that occurs during ordinary fatty acid oxidation in cellular respiration.

The basal CO₂/O₂ ratio averages 0.85, reflecting the consistent oxidation of substrate mixtures.

Oxidized substrate Avg. CO₂/O₂ ratio Carbohydrate 1.00 Protein 0.82 Ketone bodies 0.73 Fat 0.71 Ethanol 0.67 Substrate mixture 0.85 ⠀(10.1016/s0002-8223(97)00754-2)

Normal variations in diet composition and meal spacing can shift that ratio, but it tends to return to its preferred baseline, making fat oxidation difficult to avoid.

While the body often maintains everyday fluctuations under control, ROS can react with targets near their source before antioxidant defenses can act. Therefore, the most effective strategy is to prevent excess leakage from the start.

Electron leakage to oxygen is determined by their availability at susceptible sites, not by the overall flow rate. Regardless of how fast electrons are consumed, a supply that exceeds the demand leaves a surplus that's prone to leak into ROS. Because of this, a high metabolic rate is not necessarily protective.

Avoiding overeating keeps the electron supply within manageable limits, especially for fats with their tendency to generate more ROS. When the supply stays within those limits, factors that increase respiration—and thus electron demand—should help lower ROS production in the direction of "mild aerobic exercise" levels (shown above), narrowing the advantage of carbohydrates over fats and decreasing reliance on antioxidant defenses.

Stimulating respiration from the terminal side upward assumes healthy mitochondrial function, yet each metabolic pathway has its own challenges. Forcing inhibited mitochondria to respire when they can barely meet basic needs clears electrons only below the level of inhibition, risking a de-energized state. Minimizing unwanted leakage without side effects depends on efficient electron transfer and their appropriate availability throughout, so achieving it may take more than simply manipulating overall rates.