Normal Reference Ranges of Serum TSH

-

Ray Peat said in "TSH, Temperature, Pulse Rate, and Other Indicators of Hypothyroidism":

"Over a period of several years, I never saw a person whose TSH was over 2 microIU/ml who was comfortably healthy, and I formed the impression that the normal, or healthy, quantity was probably something less than 1.0."

Xing et al. said in "Factors influencing the reference interval of thyroid‐stimulating hormone in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta‐analysis (2021)":

"Some reports define the lower limit of TSH as 0.2–0.4 mU/L and the upper limit as 4.0–5.0 mU/L, but a much lower upper limit of TSH has previously been suggested based on large population studies. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologist recommended to decrease the upper limit of TSH to 3.0 mU/L. Many experts even suggest that the upper limit of the range be further reduced to 2.5 mIU/L."

"The results [of this meta-analysis] showed a higher TSH concentration in females than in males in most regions. Estrogen is an important factor affecting the TSH concentration. Low estrogen may cause hypothyroidism and then lead to an increased TSH concentration. Postmenopausal women were the typical group, and the TSH concentration increased significantly. This may be one of the reasons why TSH is generally higher in females than in males."

Ah yes, estrogen deficiency is the main culprit behind higher TSH levels in females.

"Surks et al reported that the 97.5 percentile of TSH increased from 3.56 mIU/L in the 20–29 years old group to 7.49 mIU/L in the over 80 years old group. In this study, the TSH concentration also increased with age. Some researchers have suggested that the progressive increase in the TSH concentration with ageing could be due to an enhancement in the prevalence of acquired autoimmune thyroid disease and an increase in anti‐thyroid antibodies."

"Guan et al suggested that it was necessary to consider iodine intake when establishing the TSH reference interval. Their study was conducted in Panshan, Zhangwu and Huanghua, regions with mildly deficient, more than adequate and excessive iodine intake, respectively, and the mean levels of TSH in Panshan, Zhangwu and Huanghua were 1.15, 1.28 and 1.93 mIU/L, respectively."

Biondi said in "The Normal TSH Reference Range: What Has Changed in the Last Decade? (2013)":

"An upper limit of the normal TSH range of 2 mIU/L and a lower limit of 0.4 mIU/L have been associated with a lower incidence of a progressively more deranged TSH value than other TSH values within the reference range [of 0.45 and 4.12 mIU/L]."

"Subsequent findings confirmed that ethnicity, iodine intake, gender, age, and body mass index can influence the reference range of serum TSH. In fact, the normal TSH upper limit was lower in African Americans (3.6 mIU/L) than in Mexican Americans or Caucasians (4.2 mIU/L). Reanalysis of these data 5 years later showed that the upper limit of normal serum TSH at the 97.5th percentile was 3.5 mIU/L in individuals 20–29 years old, 4.5 mIU/L in those 50–59 years old, and 7.5 mIU/L in those older than 80 years"

"...if the upper and lower limits of normal for a third-generation TSH assay are not available, an upper limit of 4.12 mIU/L and a lower limit of 0.45 mIU/L should be considered in iodine-sufficient areas. The NACB recommendation to lower the upper limit of the TSH normal range to 2.5 mIU/L should be balanced with the health and economic impact of a reduced serum TSH range. In fact, about 20–26% of the population would be hypothyroid if the upper limit of the normal range is lowered to 2.5–3.0 mIU/L."

Broda Barnes would argue that this estimated incidence of hypothyroidism is still too low.

Kratzsch et al. said in "New reference intervals for thyrotropin and thyroid hormones based on National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry criteria and regular ultrasonography of the thyroid (2005)":

"If we used the 97.5th percentile as proposed by the NACB, we found a comparable upper TSH limit of 3.77 mIU/L for the constraint and 3.63 mIU/L for the whole group. These concentrations are considerably lower than the currently used upper reference limit of 4.2 mIU/L proposed by Roche Diagnostics and the 97.5th percentile of 4.1 mIU/L from the NHANES III study. On the other hand, our values are markedly higher than 2.12 mIU/L, which was the upper limit in the study of Völzke et al. Moreover, these values are also higher than the cutoff of 2.5 mIU/L that has been proposed recently by the NACB for distinguishing between euthyroidism and preclinical hypothyroidism."

-

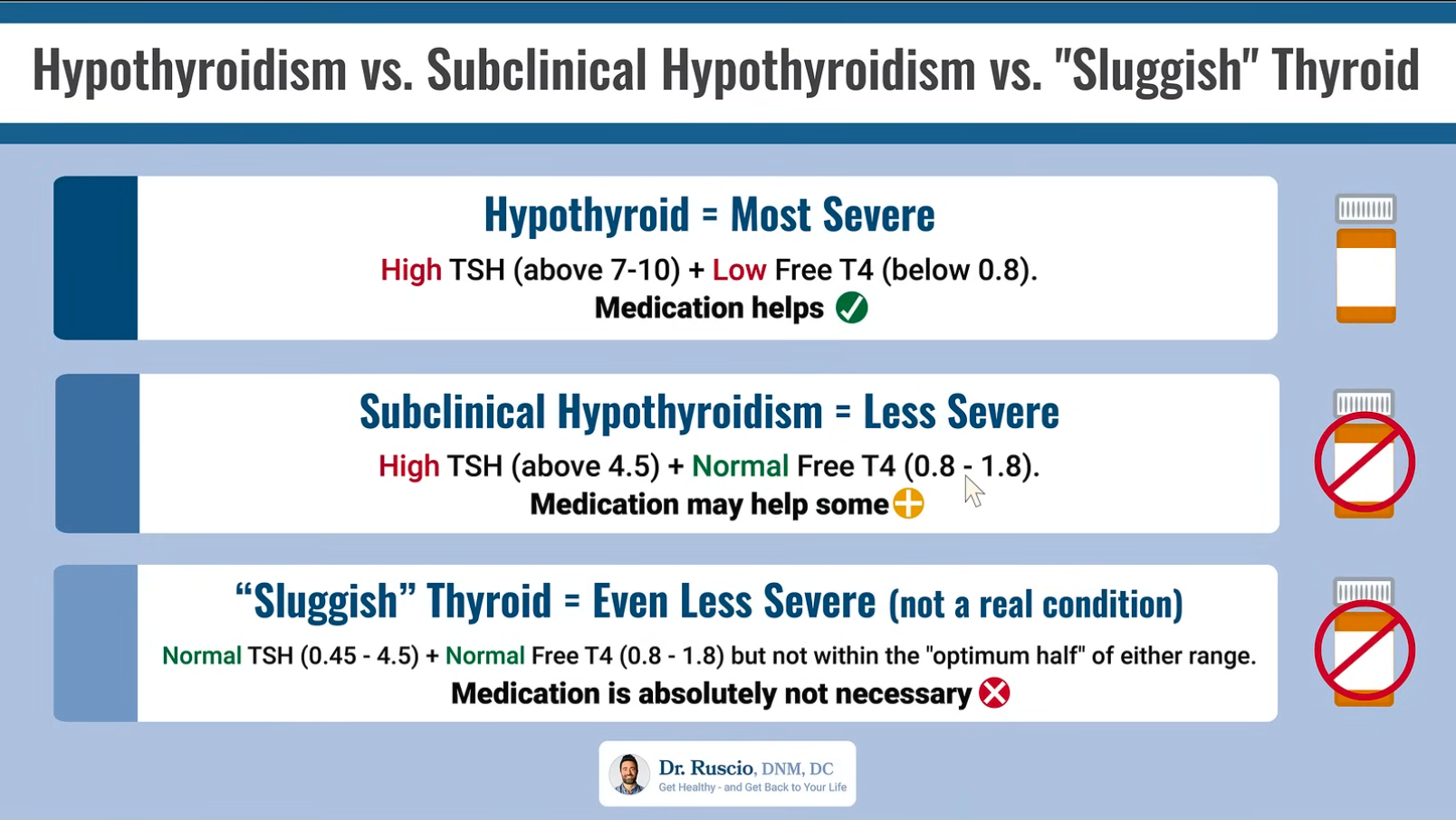

Getting the right diagnosis can be frustrating for so many hypothyroidic patients because THIS is what they're faced with when consulting an endocrinologist:

Medication is not really considered until TSH reaches dangerously high levels; T3 levels are not even considered when making the diagnosis, as if thyroid conversion is never an issue; and T4 levels are regarded as the sole marker of glandular production.

The creator of the video, from which the above chart is copied, says:

"[The most severe case is] a high TSH paired with a low free T4, according to the conventional lab ranges, not what your doctor may alter, using these different contemporary ranges, which are not correct."

"You really don't get into a position where you'll benefit from thyroid hormone, where you're considered hypothyroid, until your TSH gets somewhere above 7-10. . . . And we have pretty compelling data that answer this question: People in this subclinical range [TSH of 4.5-10] do not seem to have problems, they don't have more symptoms, and they certainly do not seem to benefit from thyroid hormone replacement therapy."

In such cases as these, where the endocrinologist is not the least bit willing to consider unconventional views, it's best to start looking for a new healthcare provider.

And of course—here's the kicker—the creator goes on to offer a $199 online course on how to manage thyroid symptoms. Yes, an online course.

-

From my personal experience, Dr. Peat is correct. My TSH was naturally anywhere between 1.80 (when I was young) and 2.85 (when I reached 40). I had hypothyroid symptoms my entire life, from hair shedding, difficulty sleeping, acne, estrogen dominance, and eventually received a diagnosis of primary biliary cirrhosis, which is a rare autoimmune disease. The specialist who treated me for that told me that 90% of his patients are hypothyroid, but I was okay because my TSH was 2.85 – nothing to worry about. It was right after that when I discovered Dr. Peat’s work. Out of curiosity, I ordered my own thyroid tests and saw that my T3 was very low, almost below range. No doctor would even listen to me about treating me with thyroid, so I self medicated. After about 8 months, ALL of my hypo symptoms went away and I no longer test positive for the autoimmune disease (I also changed my diet). Anyway, all that to say, from my personal experience Dr. Peat is correct about the TSH and about where T3 should be, and I don’t think diet alone would have fixed my situation.

-

@Wildflower I agree with you completely. That's great to hear about your recent recovery! With which type of thyroid did you self-treat (T3/T4, T3, NDT), and at what dosage? Did you encounter any setbacks in the course of your self-treatment?

-

@banquos-ghost I originally started taking NDT by the Life Giving Store, around four years ago. When I first started taking it, it worked for me but stopped working about a year after I started it (my TSH went up to 3.0 and I still had all of my hypo symptoms). What ended up working the best for me and what I take now is Cynomel (I break up one pill into four pieces and take it throughout the day with meals). Then starting around 6:00 PM, I take one drop of Tyromix. I take one drop of that every 1.5 hours until I go to bed. So, I end up taking 5 drops total of Tyromix (orally) and spread out. That amount of Tyromix is what helps me sleep throughout the entire night without waking up, and that is the marker that I use to decide the dosage of the Tyromix.